Column: The real-life Bill Cosby show: Follow the sanctimony

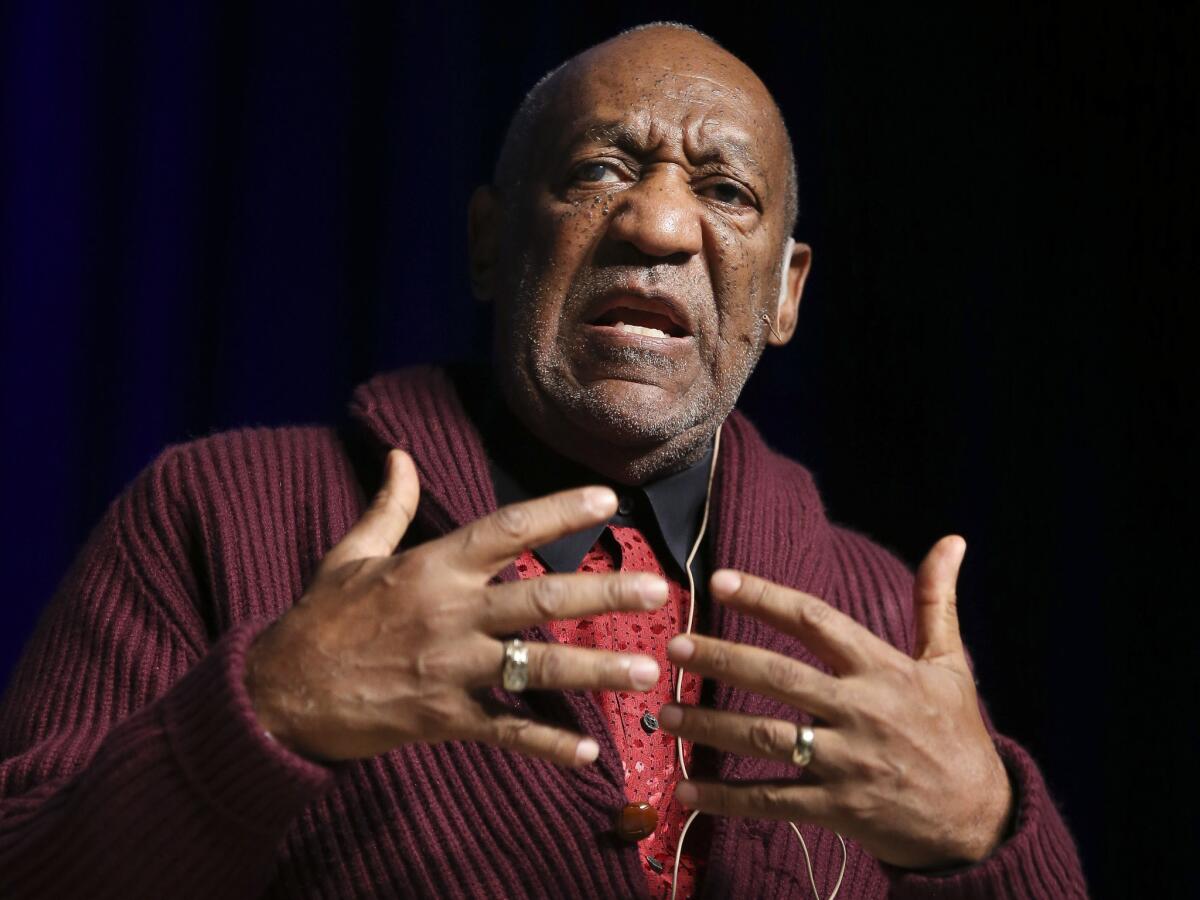

Bill Cosby has been inundated by allegations of sexual assault and misbehavior from more than a dozen women..

The phrase “follow the money” was popularized in the Watergate docudrama “All the President’s Men.”

“I’ll keep you in the right direction if I can, but that’s all. Just … follow the money,” Deep Throat supposedly told reporter Bob Woodward in the shadows of that parking garage.

Though there’s no evidence that anyone during the Watergate investigation said those words in real life (more likely they were the creation of screenwriter William Goldman), they’ve evolved into a useful rule of thumb for getting to the bottom of a shady situation.

When it comes to Bill Cosby, who has recently faced allegations of sexual assault and misbehavior from more than a dozen women, some of them involving drugging and rape, the catchphrase might be this: Follow the sanctimony.

I’m not just talking about the sanctimony of the actual Cosby, who gave speeches censuring lower-class blacks, accusing them of embracing ghetto culture and playing the victim rather than examining their own failures. These appearances, which began in 2004, may have represented the most literal manifestation of Cosby’s penchant for self-righteousness, but they were hardly without tonal precedent.

The main ingredient of Cosby’s TV-and-beyond “America’s Dad” persona was a kind of goofy affability — seasoned with more than a dash of smugness. In “The Cosby Show,” as paterfamilias at the Huxtables’ Brooklyn Heights brownstone, he wielded his authority lovingly but also imperiously. A quip to his young daughter in the third season, “Your mother and I are rich. You have nothing,” was a typical zinger. It was funny, but it was also sanctimonious.

Of course, that sanctimony contributed mightily to Cosby’s crossover appeal. Part of the reason white audiences loved Cosby so much, was that his character Cliff Huxtable’s upper-middle-class trappings alleviated white guilt by suggesting that we were in a post-racial society. Because sanctimony is a privilege afforded mostly to those who have cause to feel superior — and, as a result, it is not a trait typically associated with people of color — Cosby’s smugness functioned as a form of whiteness. No wonder the show ran for eight seasons and was No. 1 in the ratings for five years straight.

But as we’ve learned from the empty moralizing of countless evangelists and politicians (think Ted Haggard, who railed against gays but was felled by accusations that he secretly had sex with men, or William Bennett, who edited a guide to self-discipline, “The Book of Virtues,” that belied his own gambling problems), sanctimony can often function as a clever disguise for serious moral failings. Follow it far enough and you’re likely to find behavior that flies in the face — sometimes at lightning speed — of all that piety.

Granted, Cosby’s sermonizing has mostly been focused on the importance of education and good parenting, where he does have some legitimate bona fides. Unlike today’s reigning America’s Dad, Louis C.K., whose hands-on parenting style is taken as a given and represents a generation of men raised on feminism, Cosby was never particularly held up as a champion of women’s rights. Still, he was so hellbent on holding himself up as a pillar of the community that in retrospect it seems almost logical that he might be hiding a more sinister side.

Nonetheless, the public was caught off guard by the cascade of charges. And if the audience that gave Cosby a standing ovation at his comedy show in Florida on Friday is any indication, some people remain unwilling to believe that Cosby’s actions were as bad as they now look to be.

Part of that is surely a function of the special brand of denial we reserve for beloved celebrities. But an even greater part might be the degree to which so many people are swayed by sanctimony and moral censure. As much as it hurts to be scolded, there can also be a masochistic pleasure in it. Moreover, there’s no pleasure quite like watching others get scolded, especially when the scolder is calling out members of his own community in a way that outsiders cannot.

Cosby, who perhaps understood his audience better than they understood themselves, delivered that pleasure by the truckload. His smugness functioned not just as a cover for his own actions but as a pacifier — a drug, even — for a public too seduced by sanctimony to trace it back to its less-than-noble roots.

Twitter: @meghan_daum

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.