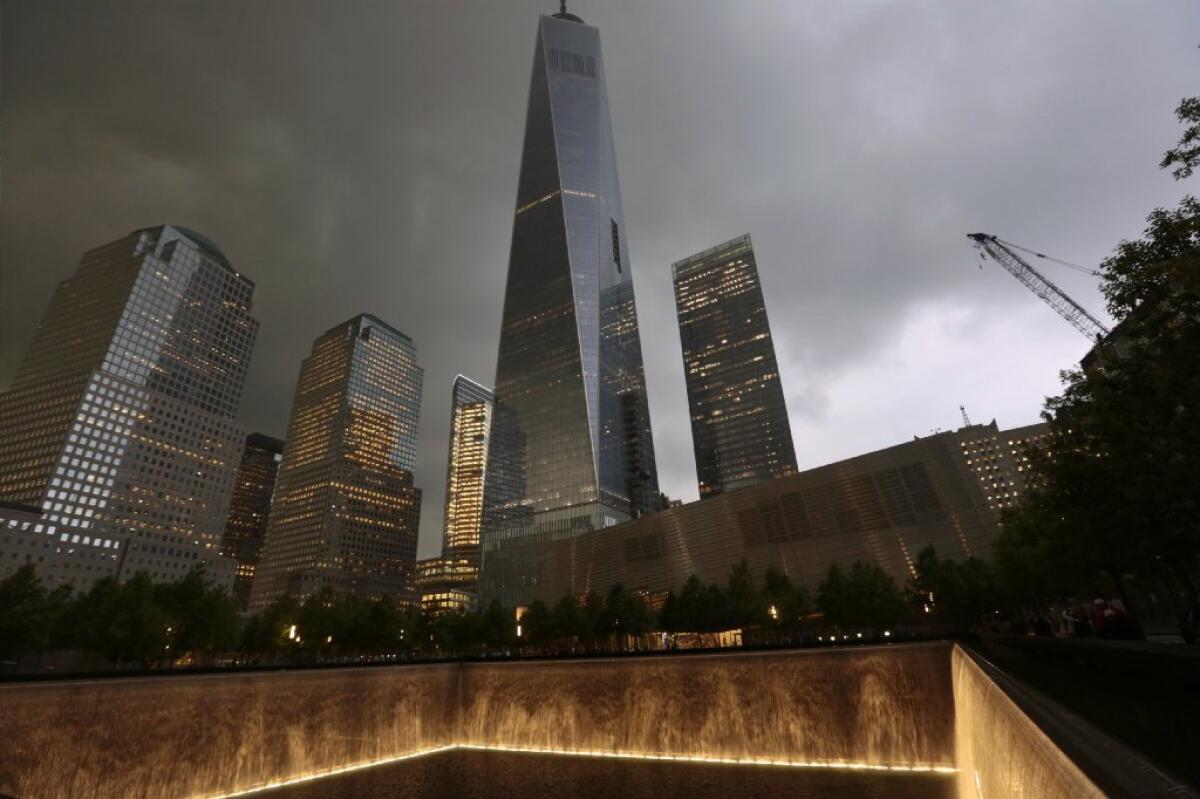

Opinion: Writing on the 9/11 memorial -- graffiti or grief?

New York cops have a tricky situation on their hands: What to do, or not do, about the relatives and friends of 9/11 victims who have begun scratching messages into the bronze plaques bearing the names of victims at the new 9/11 memorial.

Technically it’s an act of criminal mischief, but police wisely aren’t even trying to figure out who did it; who would want to arrest a relative who had cut “Love 4Ever” alongside a victim’s name?

But if the practice doesn’t get addressed in some way, it could become its own “broken window” opportunity, inviting all kinds of vandalism from strangers, conspiracy theorists and thugs with cruel things to say. That graffiti would suck the humanity out of the memorial and degrade its meaning, turning it into the bronze version of some website’s unmoderated message board.

The dead of 9/11 are members of our national family, and maintaining the memorial’s dignity will be as important as building it in the first place.

For now, employees are using a “black patina” to cover the messages, or more intensive restoration, if necessary. But there’s a better solution, and it’s at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington.

For 30 years, its black stone walls, with the names of tens of thousands of dead, have been a destination for pilgrimages by family and friends, strangers and people who weren’t even born until after the war ended. There, at the foot of the wall below a loved one’s name, people have left more than half a million items -- medals, photos, flowers and dog tags.

The National Park Service archives and catalogs pretty much everything but the flowers, and for about 10 years, some of these were put on exhibition at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, in a display titled “Personal Legacy: The Healing of a Nation.”

The 9/11 Memorial Museum already displays multimedia images and bios of the nearly 3,000 victims, and remembrances from those who knew them. That may be the right place for families and friends to mark down more vividly their immediate, powerful grief and longing when they come to visit, and, as they do at the Vietnam Wall, to leave objects and notes that convey a richer sense of each life lost.

That would still convey both the harrowing humanity of the place, and the integrity and grandeur of the monument; to paraphrase Secretary of War Edwin Stanton at Lincoln’s deathbed, it too belongs to the ages.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.