The Road to Selma: Bob Zellner and the war for justice

Tomorrow, Selma will greet the president, the dignitaries, the Civil Rights Movement survivors and various politicians hoping to grab a little notoriety in the midst of the 50th anniversary commemoration of “Bloody Sunday.” As they all gather and speechify, they will extol the heroism and sacrifice of the movement’s leaders and many foot soldiers.

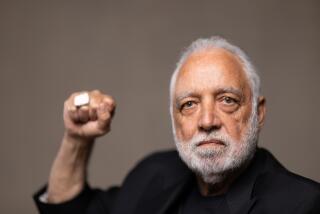

Seated up near President Obama will be one foot soldier who quickly grew into a leader, Bob Zellner. He may be 75 years old, but he is nowhere close to retiring. This white, Southern, self-described radical is still teaching, organizing and carrying on with the cause of bringing social change through nonviolent action.

Zellner has been riding on the “52 Strong” pilgrimage bus with us for the last couple of days. He is a jovial, sweet-tempered man; as wise, warm and welcoming as your favorite grandfather. When he describes the many times he was imprisoned or nearly killed, he does it with a laugh in his voice. Only when he speaks of the activist friends who were murdered along the way do his eyes fill with tears.

On Thursday, our group was stuck for much of the day at a hotel in Granada, Miss., thanks to the snow and ice that hit the region overnight. Luckily, we had Zellner to gather around. We asked a lot of questions and he shared his eyewitness insights into life on the front lines of the civil rights struggle.

Much of the time, as Zellner described it, it truly was a war zone, with heavy casualties and a relentless enemy. While the redneck cops and Ku Klux Klansmen had guns, cattle prods and clubs, Zellner’s side had only the power of their training in nonviolence and a willingness to sacrifice their lives to win African Americans the right to vote and live like free Americans. Zellner said he and his troops survived on prayer, singing and humor — humor in even the ugliest, vermin-infested prison cells.

One thing Zellner sees as too ironically amusing is the way his friend Martin Luther King Jr. has been co-opted by the heirs of the 1960s right-wingers who demonized King when he was alive. As King has been turned into a secular saint, Zellner said, his message has been simplified into a comfortably bland philosophy of peace and brotherhood. When conservatives like Glenn Beck lay claim to King’s legacy, he said, it is a cynical act.

“He was a radical,” Zellner insists. “He called it a revolution. His plan was to get poor people and working people together with strong leadership.… To say that ‘St. Martin Luther King’ is the same as the real Martin Luther King is laughable.”

We talked with Zellner for a couple of hours. By then, the sun had come out, the ice cleared and we all got aboard our bus. By evening we at last arrived in Selma.

At the Tabernacle Baptist Church, a mass meeting was just getting started. The crowd was spilling out the doors, but we wedged into the sanctuary any way we could. A choir was performing a rendition of “Abraham, Martin and John,” the classic tribute to America’s most famous victims of assassination, but, in this version, the names of the fallen were not Lincoln and Kennedy; they were the names of martyrs of the civil rights struggle. Martin — Dr. King — was the last name sung. By then, everyone in the packed hall was singing along and the voices transitioned smoothly into “We Shall Overcome.”

It was a moment of sudden uplift after all the miles spent on a winding path through sites of tragedy and violence. I noticed Bob Zellner had moved up to the front, singing with passion. A few minutes later, when the songs were done, the old Freedom Rider Bernard Lafayette stepped up to the pulpit, looked down and saw his old comrade, Zellner, packed in with the young people sitting on the floor.

“Is that you, Bob?” Lafayette said. “I remember when Bob joined SNCC — he got arrested the first day.”

Of course he did. And he appears perfectly ready to get arrested again, if need be. But, first, he has a date with the president.

Late Friday morning, before he left us to go link up with the big shots, Zellner led us as we walked in silence, two-by-two, across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in the steps of the marchers on Bloody Sunday. It was good to make the crossing before the arrival of the huge crowds on the weekend. We had the bridge walkway to ourselves. The tingle of history was palpable. Passing under the bridge was the wide, brown water of the Alabama River — a river once used to ship enslaved people and spanned by a bridge named for a Confederate general and alleged Grand Dragon of the KKK.

We summited the steep rise of the bridge. That is the point where the marchers a half-century ago first saw the line of police and deputized white men eager for bloodshed arrayed across the highway. This day, there was just local traffic and sunshine, but as I scanned the four lanes of the bridge, my mind’s eye blinked on the image of frantic, retreating marchers in a shroud of tear gas being beaten by vigilantes’ clubs and run down by cops on horses.

In the park on other end of the bridge we gathered around Zellner, the grandson and son of KKK members, who has spent a lifetime fighting racist violence and entrenched forms of discrimination. Smiling, he told us not to let the experience of crossing the bridge weigh too heavily. That message was aimed particularly at the students in our group — black, white, Asian, Latino and racially mixed — who have done plenty of hard, emotional work in the last few days to mesh all this harsh history with their own life experiences.

Zellner left with a gentle admonition: Make your lives about something that you are willing to sacrifice and even die for.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.