As ‘Dreamers’ program is phased out under Trump, Congress is split on protecting them

The Trump administration began unraveling the Obama-era program shielding people brought to the United States illegally as children from deportation, though a split Congress has made no progress on writing similar protections into law as President Trump asked.

The phaseout of the five-year-old Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program began at midnight Thursday. The administration is no longer accepting or processing new or renewal applications for so-called DACA protections, even if they were mailed before the deadline.

Now, with five months to go before hundreds of people daily begin losing their legal status, Congress is struggling to respond to Trump’s request for a legislative solution over an issue that has traditionally divided lawmakers along partisan lines.

The popularity of the so-called Dreamers, however, has prompted an unusual number of Republicans to favor action to provide them with legal status, even as conservative hard-liners continue to denounce such legislation as “amnesty.”

“We need to stop talking about it and solve it,” Sen. Thom Tillis of North Carolina, a Republican who has cosponsored one proposal, said earlier this week at a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing. “We know what a reasonable solution is, and we should provide it.”

Permits already issued to live, work and serve in the military will begin to expire after March 5, continuing over the following two years. When Trump announced last month that he was ending the program, he said the delay would give Congress six months to send him legislation to put alternative protections into law for the roughly 800,000 Dreamers who have qualified for two-year permits to remain in the U.S. without threat of deportation.

Of the estimated 154,000 people who were eligible to apply for renewals, about 118,000 had sent in applications to the three federal processing centers in Phoenix, Dallas and Chicago by Wednesday, according to the Department of Homeland Security. Officials will only process applications that were received by the end of the day Thursday, and will not consider forms postmarked Thursday but arriving later, said David Lapan, a spokesman for the Homeland Security Department.

That left some 34,000 DACA beneficiaries — just under one in four of those eligible for renewal — who had yet to file in the final days before the deadline and who could lose their protected status and their authorization to work.

In a related matter, the American Civil Liberties Union and the ACLU Foundation of Southern California filed a class-action lawsuit Thursday on behalf of DACA beneficiaries, alleging that even before the program’s phaseout, the administration was revoking beneficiaries’ protections for minor offenses like traffic infractions or charges for which they were ultimately cleared.

Democrats in Congress, including Sen. Richard J. Durbin of Illinois, had repeatedly urged the department to extend Thursday’s deadline, especially for people living in disaster zones in Texas, Florida and Puerto Rico. The Congressional Hispanic Caucus asked the administration to reset the deadline to January. But the Trump administration refused to move the dates.

Thursday’s deadline was “both cruel and arbitrary,” said Lorella Praeli, director of immigration policy at the ACLU.

Immigrants’ advocates had scrambled to notify those who were eligible for a final renewal to take action, and expressed frustration that the government hadn’t reached out to DACA participants to alert them to the changes.

Since 2012, under President Obama’s order, people who qualified could apply for protected status if they paid a $495 fee and submitted to a federal background check. Renewals every two years required the same steps. The fees covered program costs.

But Trump’s personal interest in “these incredible kids,” as he has called Dreamers, as well as polling that shows overwhelming public support for the mostly young people, has led more Republicans to join Democrats in considering legislation benefiting them.

Trump “very much” wants Congress to find a solution for the Dreamers, Michael Dougherty, a senior immigration policy official at the Department of Homeland Security, told the Senate Judiciary Committee on Tuesday.

“They’re a benefit to the country, as are many immigrants coming in,” Dougherty said. “They are a valuable contribution to our society. We need to regularize their status through some legal means.”

The White House is expected to send guidelines to Congress soon for what it wants to see in legislation. An immigration task force of House Republicans formed by House Speaker Paul D. Ryan (R-Wis.) has been meeting almost daily to assess options that could win majority support.

Democratic leaders — House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi of San Francisco and Senate Minority Leader Charles E. Schumer of New York — said that Trump told them during a Chinese food dinner at the White House in mid-September that he was willing to sign the Dream Act as part of a broader package that also increased border security. But some Republicans in Congress and the administration have cast doubt on Trump’s commitment to the Democrats on Dreamers.

“We know what the president said. On the Dream Act, the president was committed,” Pelosi said Wednesday.

Schumer agreed, and said: “If they’re backing off it because of pressure from the hard right, America ought to know.”

Several bills are making their way through Congress, including one from Republican Rep. Carlos Curbelo of Florida that puts Dreamers on a potential path to citizenship; it has more than 20 GOP sponsors in the House. Another, from Tillis and fellow Republican Sen. James Lankford of Oklahoma, also offers a citizenship process.

Another possibility would be to tuck a DACA and border security agreement into a must-pass bill to fund the government that is due by Dec. 8.

Democratic leaders, though, have been reluctant to engage on options other than the terms of their Dream Act, the nearly 20-year effort to provide the young immigrants with legal status and a path to citizenship.

In July, Durbin and a Republican ally, Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, introduced the latest Dream Act. It would allow some people who were brought to the United States illegally as minors to apply for lawful permanent residence and eventually citizenship.

But Trump has signaled in recent weeks that he will only sign a narrower bill that would allow only people who qualify for DACA to receive protections rather than expanding coverage to a broader pool of immigrants.

That would exclude, for example, close relatives of those who have benefited from the existing program. DACA beneficiaries would not be allowed to sponsor relatives for migration to the United States.

White House officials have also said that any law to replace DACA should come with more money for immigration enforcement, but Democrats — and many DACA beneficiaries — oppose proposals to toughen action beyond the border areas, fearing it would lead to more raids and deportations of non-DACA immigrants from the interior United States.

Some lawmakers say seeking too comprehensive an immigration bill in Congress’ short time frame could doom the effort.

“Don’t put the entirety of immigration reform on the Dreamers,” Durbin said. “It’s too much to ask.”

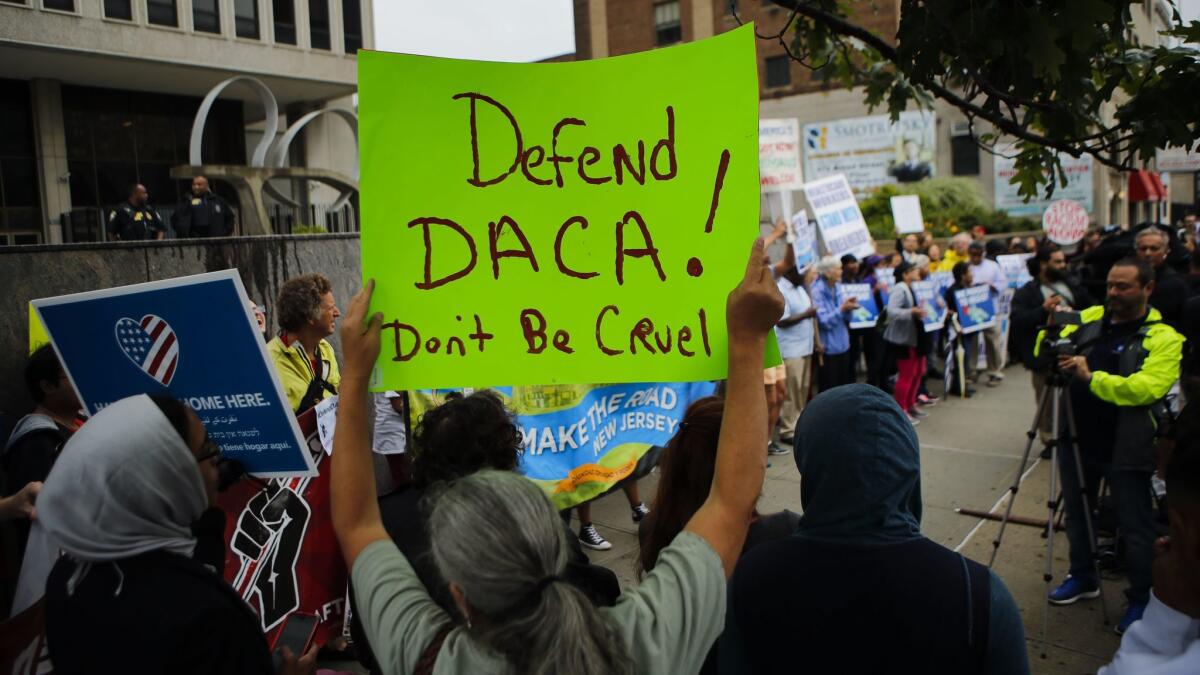

Dreamers have flooded Capitol Hill this week, knocking on lawmakers’ doors and rallying outside the Capitol.

Californian Denisse Rojas Marquez, 28, a DACA beneficiary who is studying to become a doctor, says she and others will face hardships if the protection expires.

“I have loved this country for as long as I can remember,” said Marquez, who told senators how she arrived from Mexico as a 1-year-old, settling with her family in Fremont and eventually graduating from UC Berkeley in 2012, all the while fearful of being deported.

“Terminating DACA means I will not be able to practice as a doctor,” Marquez said. “It means that every aspiration and goal I have will once again be made unreachable.”

Twitter: @ByBrianBennett

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.