Capitol Journal: Give Newsom credit for halting the death penalty in California. Brown and Harris dodged the issue

Give Gov. Gavin Newsom credit: He had the guts to act on his convictions and declare a moratorium on the death penalty in California.

It may be virtually moot. California hasn’t executed a murderer since 2006 and doesn’t even have an approved method for administering lethal injection. The state has executed only 13 since it reinstated capital punishment in 1978.

But Newsom’s action stands in stark contrast to two other prominent California Democrats who oppose the death penalty — U.S. Sen. Kamala Harris and former Gov. Jerry Brown.

Harris and Brown remained utterly mute when death penalty repeals were on the ballot in 2012 and 2016. Both measures failed narrowly, probably because they lacked support from the political top. As California’s attorney general, Harris even defended the death penalty in court.

Harris’ example is the most relevant because she’s now running for president as a fighting liberal. As attorney general, she was anything but on capital punishment.

On Wednesday, Harris praised Newsom’s announcement that he wouldn’t allow any executions during his time as governor. She called capital punishment “immoral, discriminatory, ineffective and a gross misuse of taxpayer dollars.”

But Harris took a hike when there were ballot initiatives to resentence every murderer on death row to life without the possibility of parole. Neither did she take a position on a rival measure to expedite the death penalty. It narrowly passed.

Harris’ excuse was that it was her ministerial duty to write the official title and summary for ballot propositions. So she didn’t want to taint her work by supporting or opposing measures. But except for her predecessor, Jerry Brown, all previous attorneys general had taken positions on ballot measures.

Her real motive in not fighting to repeal the death penalty, it seemed, was to avoid making political enemies among a key constituency: law enforcement.

Brown has been a lifelong opponent of the death penalty. But in 2012 the then-governor was pushing his “soak the rich” ballot initiative, and in 2016 was sponsoring a ballot measure to reduce prison sentences. He figured that thrusting himself into the death penalty fight could jeopardize his own ballot measures.

Then-Lt. Gov. Newsom publicly supported both death penalty repeals. As for political leaders who stayed on the sidelines, he told me in 2015: “It frustrates me no end. I get the politics, but….”

While Newsom deserves kudos for acting on his convictions — “The intentional killing of another person is wrong” — he opened himself up to attack for ignoring the voters. They’ve decided twice in the last eight years to keep the death penalty.

Coverage of California politics »

When a governor solemnly swears to “support and defend” the state Constitution and “faithfully discharge the duties” of office, is that for real or just a throwaway line?

“With one stroke of the governor’s pen, he has defied the will of the people,” state Senate Minority Leader Shannon Grove of Bakersfield charged.

That was a common reaction of Republicans. But Grove also said that Newsom acted “well within his authority … to impose a moratorium on the death penalty.”

There’s undoubtedly enough counterargument for a court challenge.

The state Constitution says that all death penalty statutes “are in full force and effect, subject to legislative amendment or repeal by statute, initiative or referendum.” It doesn’t say anything about a governor halting capital punishment by declaring a moratorium.

The Constitution does provide gubernatorial power to grant a “reprieve.” Is that similar to a “commutation,” which requires approval by the state Supreme Court if the prisoner is a two-time felon? Judges may be asked.

We’re in unchartered territory.

The last governor to call a moratorium on capital punishment was Brown’s father, Pat Brown, in 1960. At his son Jerry’s urging, he briefly stayed the execution of convicted robber, rapist and kidnapper Caryl Chessman, the “Red Light Bandit,” and asked the Legislature for an official moratorium. It refused.

“For that I was called every foul name in the book,” Pat Brown wrote in his autobiography. “My family was booed in public. My political stock fell so low that there was talk of a recall. Then when I followed the law and the will of the people and allowed Chessman to be executed, the reaction was equally intense.”

Pat Brown opposed the death penalty. But he sent 36 to the gas chamber while commuting the sentences of 23 to life imprisonment. He recalled that the issue “seriously damaged my political future.”

Newsom’s political future will probably be helped, at least among Democrats who have been veering left as fast as the GOP has been careening right. This should raise the new governor’s national profile.

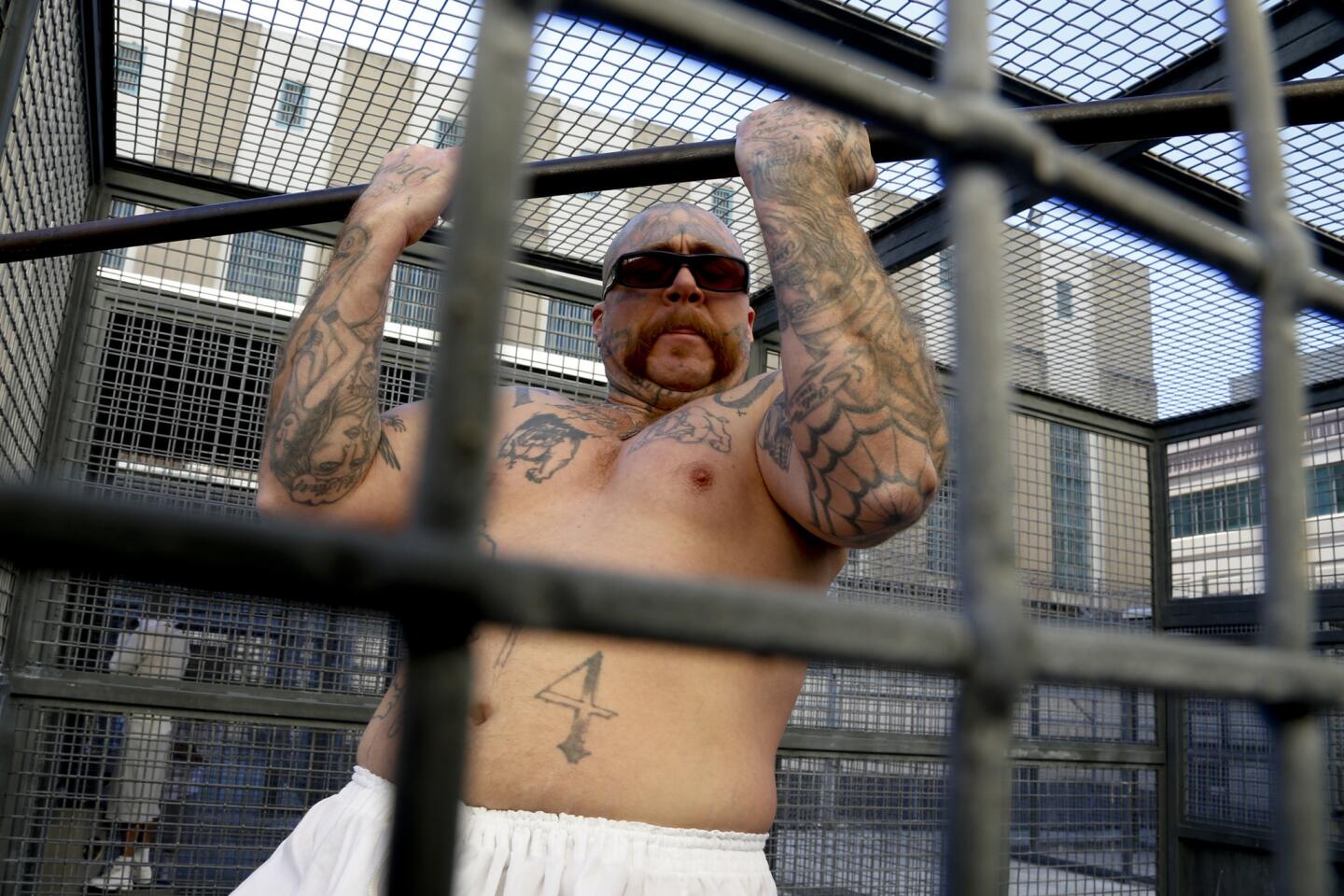

The temporary reprieve of 737 condemned inmates on San Quentin’s death row was the big flashy act that we were awaiting from Newsom. It’s his style.

The first example was his allowing same-sex couples to marry when it was illegal. He did that in 2004 shortly after becoming mayor of San Francisco. The bold act led to gay marriage becoming legal across the country.

The most straightforward way to end capital punishment is for the Legislature to pass a constitutional amendment and place it on the ballot. Assemblyman Marc Levine (D-San Rafael) introduced such an amendment Wednesday. It will require a two-thirds vote in each house — a long reach.

But this time there’ll be a governor helping the fight.

Follow @LATimesSkelton on Twitter

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.