Capitol Journal: Should barbaric boxing be KOd?

What if a legislator introduced a bill that allowed adversaries to settle disputes by pounding each other until one was beaten senseless?

The lawmaker would be ridiculed and maybe referred to a shrink.

But the pummeling is legal when it’s called boxing — a sport with the sole purpose of beating someone into unconsciousness.

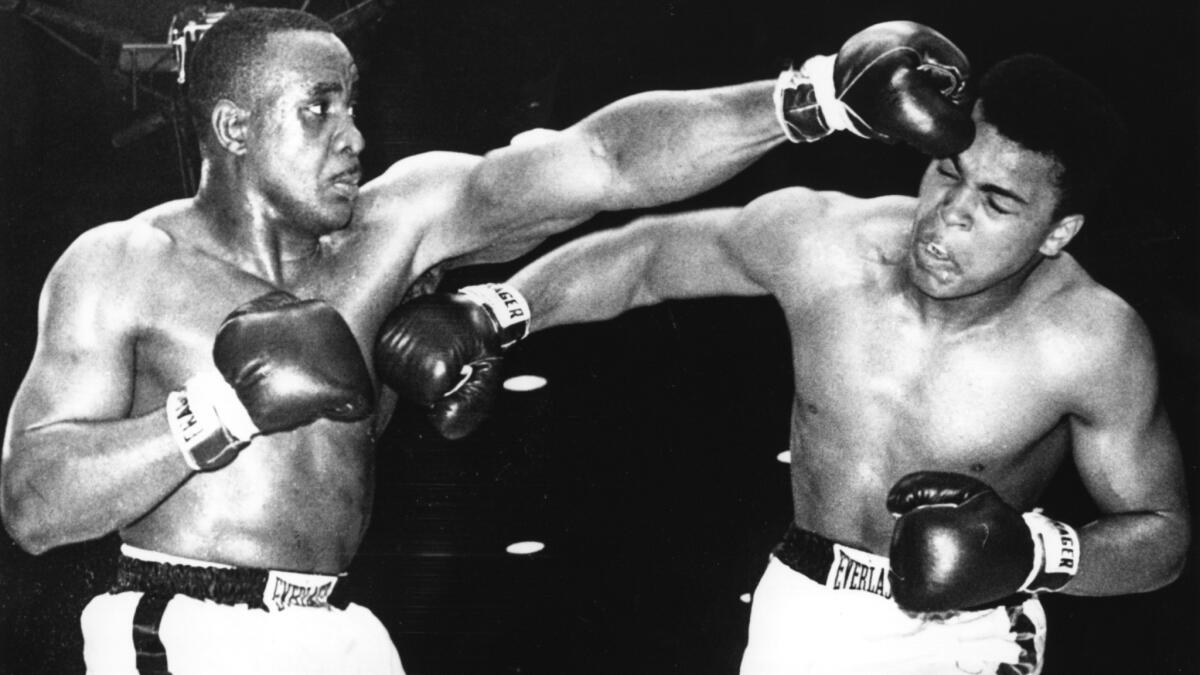

I began thinking about this again last week after Muhammad Ali died at 74, his having suffered from Parkinson’s for three decades. No one knows for sure whether all those head blows caused Ali’s deteriorating neurological condition. But no one argues they didn’t contribute, either.

As former Times sports editor Bill Dwyre wrote, “He had 61 fights and that was probably 20 too many.” Many people who never boxed get Parkinson’s, Dwyer continued, but like so many fighters, “Ali got hit in the head a lot.”

Jonathan Gottschall, a Washington & Jefferson College English instructor who took up mixed martial arts and wrote a book called “The Professor in the Cage: Why Men Fight and Why We Like to Watch,” put it this way:

“The main objective of fighting sports is to temporarily shut down the other guy’s brain. Head punches hurt what they are designed to hurt, not the face, the brain.”

I thought about this even more when I read a letter to the editor last week in The Times.

“We talk freely about the effect of head injuries on football players and our fighting forces,” wrote Joan Walston of Santa Monica. “Boxing … has been exempt… It should never be that way again.”

All this pains me because I grew up a boxing fan. Joe Louis was right up there with Babe Ruth and FDR in our house. I eagerly looked forward to “Friday Night Fights” while eating dinner on a TV tray.

But my vision of boxing became blurred when, as a young reporter for UPI, I covered a match in which a fighter was pathetically knocked down — if I recall correctly — seven times in one round. In the next round he was floored twice before the bout was mercifully stopped.

The fighter was Terry Smith, an ex-collegiate champion and alternate on the 1960 U.S. Olympic team. Ali — then named Cassius Clay — won a gold medal with that team. Smith wisely hung up his gloves soon after the thrashing and had a successful career as a deputy district attorney and boxing referee/judge.

Around then in the early 1960s, the great Times sports columnist Jim Murray — a Pulitzer Prize winner and 14-time national sportswriter of the year — covered a featherweight title fight at Dodger Stadium where the champ, Davey Moore, was beaten and soon died from brain injuries.

“Do we swallow our conscience one more time and continue to ban bullfights and cockfights while continuing to sanction prize fights?” Murray wrote. “Are animals more precious than human beings? Are duels at dawn more immoral than death in the evening? Do we sell tickets to an execution? Is this the 20th Century or the Roman Empire?”

Murray wrote eloquently about boxing and had mixed feelings.

“There is no moment in sports to rival the electric charge that goes through an audience in the moments just before the bell for a championship fight,” he once wrote.

But he stayed on boxing’s case his entire career. “Justifiable homicide,” he characterized it in 1982. “On a street corner, someone would go to jail.”

“Muhammad Ali probably was the most stunning physical specimen any sport ever produced,” Murray wrote in 1992. “Two decades later, Ali, the quick-witted, quick-tongued artist of the squared circle, would be a shambling, stumbling, stuttering, mumbling replica of himself.”

There’s no question that repeated blows to the head can damage the brain. It’s why football, hockey and baseball players wear helmets. So do amateur boxers, but not pros. In other sports, head injuries occur by accident. In boxing, it’s the whole purpose.

Louis developed dementia symptoms. The great Sugar Ray Robinson died with Alzheimer’s. There’s a long list. They used to call it being “punch drunk.”

California has had a zigzag history with boxing. The original state Constitution outlawed prize fighting. Later amateur boxing was allowed. Professional bouts occurred anyway, but underground. Finally voters legalized it in 1924.

Gov. Pat Brown tried to outlaw boxing in 1963.

“Even under ideal conditions,” he said, “it’s a brutal sport — if it can be called a sport.”

Brown’s son Jerry, the future governor, boxed in high school and once decked an opponent.

Pat Brown couldn’t get the Legislature to ban boxing. But it did tighten regulations. And Sacramento has continued to tighten them.

“Right now boxing is safer in California than ever before,” says Andy Foster, executive officer of the State Athletic Commission, which regulates boxing and mixed martial arts. “But that doesn’t mean it’s safe. This is not a safe sport. That’s why it’s regulated.”

The commission monitors matchups to make sure they’re balanced. It regularly orders neurological and other exams. And it suspends fighters after repeated knockdowns.

Foster, a former amateur boxer and professional mixed martial arts combatant, says: “Fighting is part of human nature. People compete. Fighting has been around since 4000 B.C.

“It would be disingenuous to say you can’t have any more fights. They would just go underground. Then they’re not going to be regulated.”

Boxing won’t be banned any time soon. But you can hear the bell tolling.

Follow @LATimesSkelton on Twitter

ALSO

Sights and sounds from Muhammad Ali’s funeral

Op-Ed: There will never be another Muhammad Ali. Athletes today are too rich to take political risks

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.