When Muhammad Ali first heard Vin Scully ...

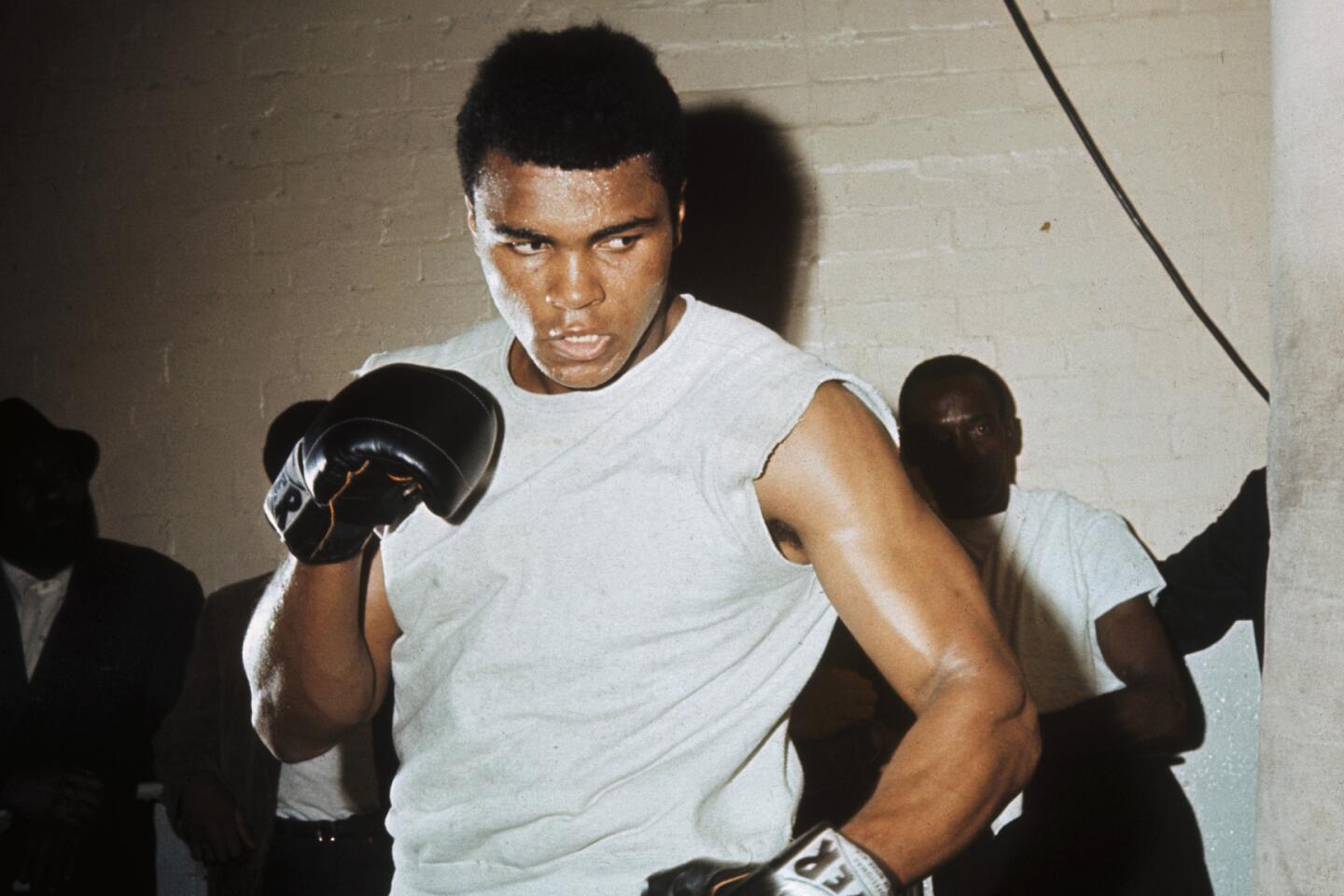

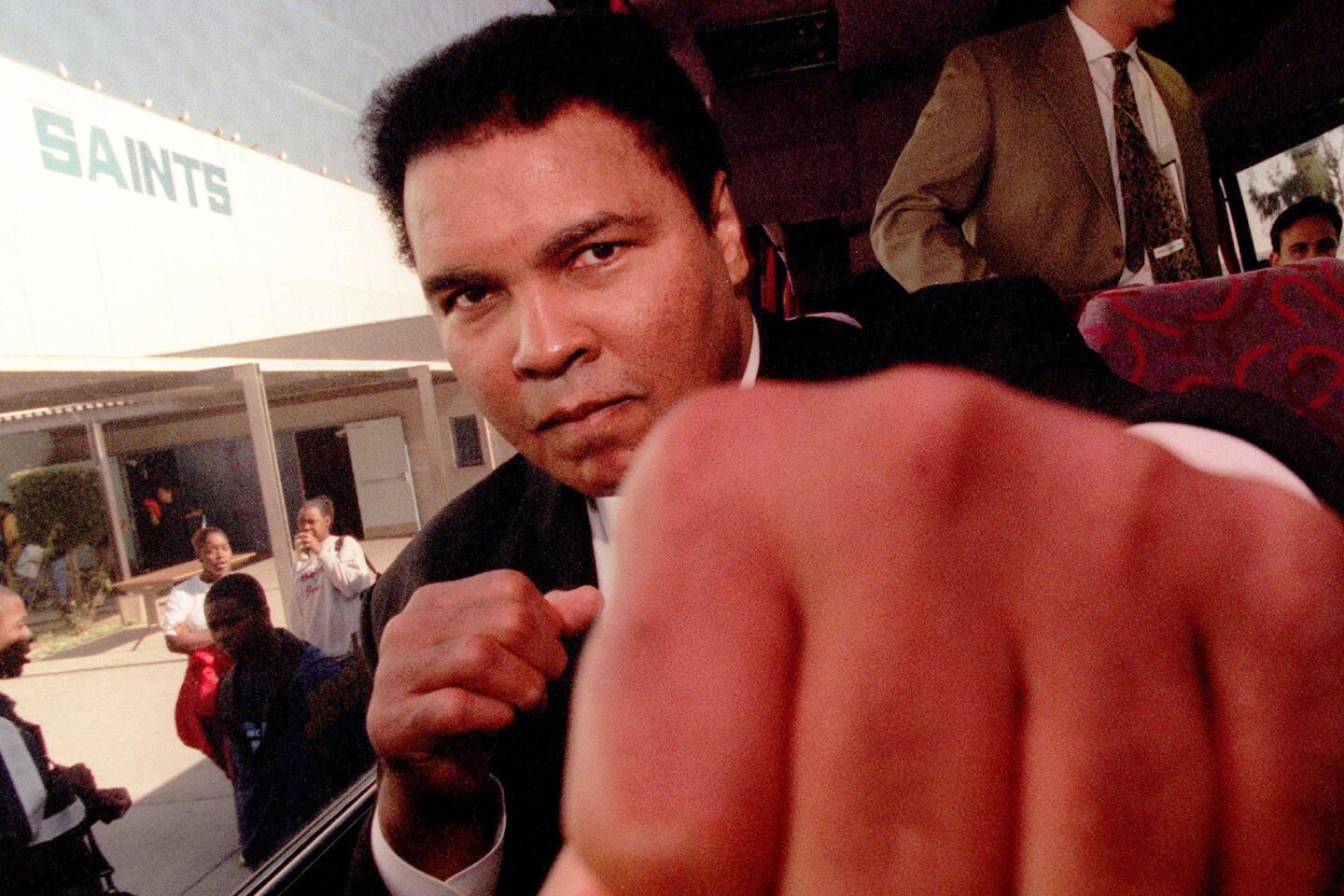

Muhammad Ali stared down curiously from the boxing ring at the famed Main Street Gym in downtown Los Angeles, asking the man with the device pressed to his ear, “What you got there?”

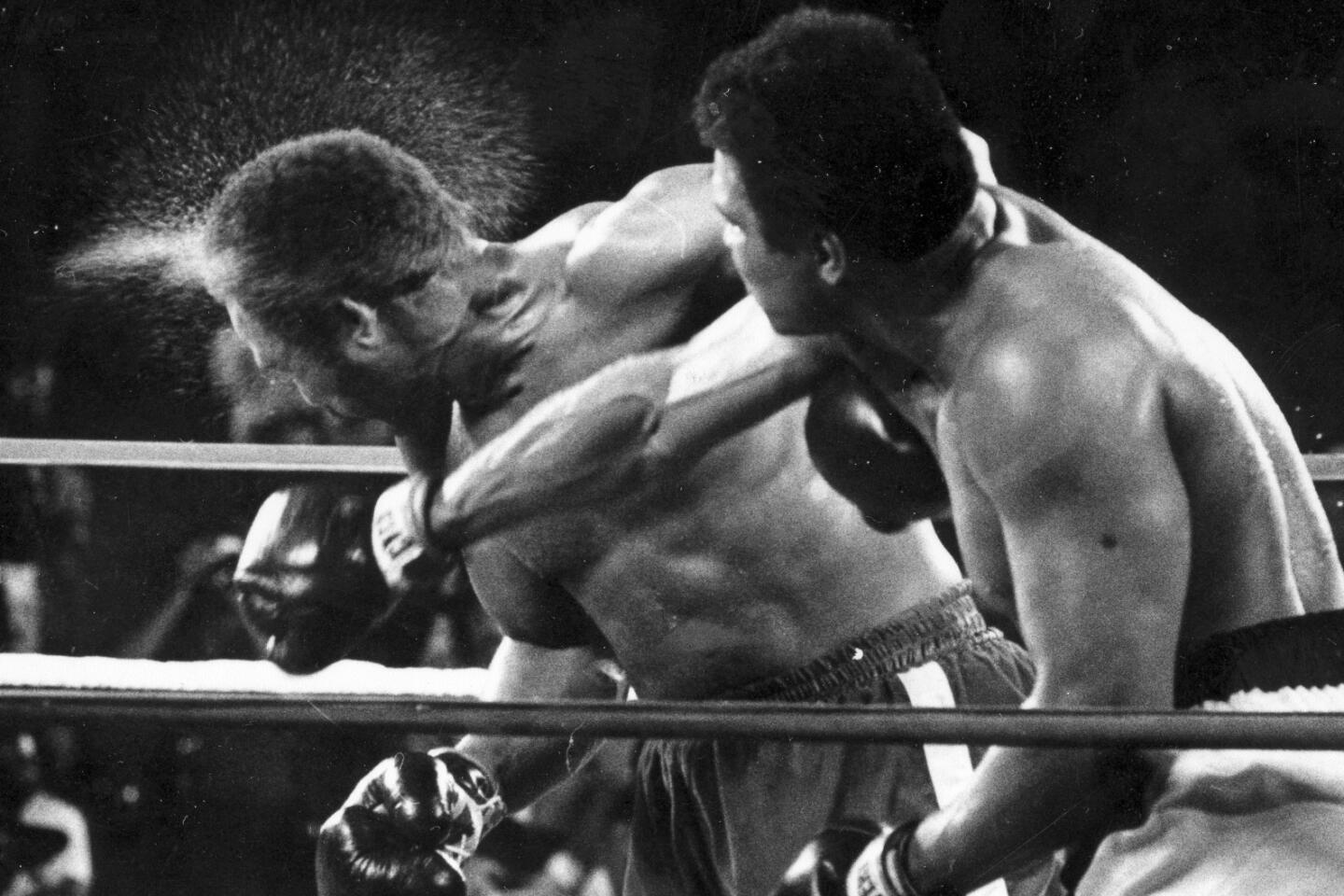

It was April 1962, only a few days after the opening of Dodger Stadium and just a few days before Ali was to stage the first of his three bouts that year at the Los Angeles Sports Arena.

Ali, then 20, had never before seen anything like the red Zenith transistor radio that then-frozen food salesman Bill Caplan was holding.

Simultaneously watching the greatest boxer in history train while listening to the best sports broadcaster ever, Caplan, who’s now a Hall of Fame boxing publicist, told Ali, “It’s a transistor radio.”

Ali was stunned. He’d only previously seen larger, more cumbersome radios, not this transistor that was slightly larger than a cigarette pack.

“Radio? What are you listening to?” Ali asked Caplan.

“I’m listening to the Dodgers and Vin Scully,” said Caplan, a lifelong fan of the team.

“Can I see that?” Ali asked.

“I handed the radio to him with Vinny’s voice calling the action,” said Caplan, and Ali listened to Scully, expressing excitement about the clarity of the signal even if his interest in the game seemed passing.

“Does it play music too?” Ali wondered.

“Sure,” Caplan said, pointing him to the AM radio dial. “Go ahead and find some music.”

It was unclear who was more impressed that day, Caplan or Ali.

Caplan was maybe the only regular Joe in the Main Street Gym that day. He’d learned through word of mouth that Ali was at the gym and found a way in on the coattails of his brother-in-law, Larry Rummans, a matchmaker/cornerman/jack-of-all-trades who’d allowed Caplan to tag along and learn more about boxing at meetings like post-fight meals at the Brown Derby.

“I paid more attention to boxing than my job,” Caplan admitted.

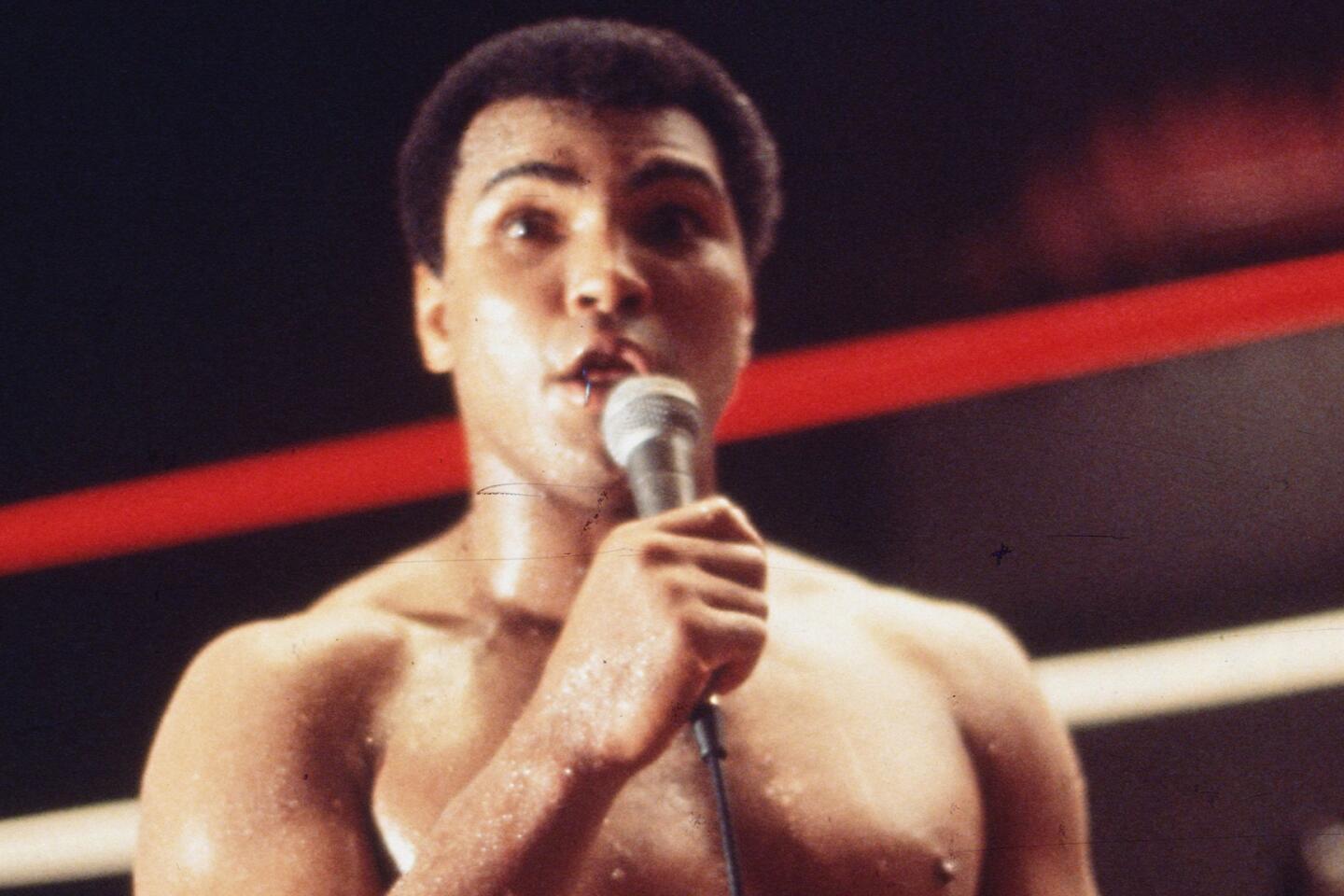

Watching Ali, then two years removed from his boxing gold medal at the Summer Olympics in Rome, was a revelation.

“What impressed me so much about Ali was that he was moving backward faster than what most guys can run forward,” Caplan said. “Those legs were unbelievable. It was something I had never seen before. He was a big — 6-foot-3 — heavyweight, real big in those days compared to [Rocky] Marciano and [Floyd] Patterson. But he could move incredibly.”

Yet, Ali was in awe of Caplan’s possession, telling the gym visitor, “I’ve got a wire recorder in my hotel room. Could you come to my hotel room with me and see if I can record this music on my wire recorder?”

Caplan responded, “Sure,” waiting for Ali to shower and dress at the gym, then handing off the radio with the Dodger game’s outcome in limbo as they walked from the upstairs gym at 218½ Main Street to Ali’s Alexandria Hotel suite at 5th and Spring.

“I lost my ballgame, but it was an intriguing toy to him. I was OK with that. He was Ali,” Caplan said.

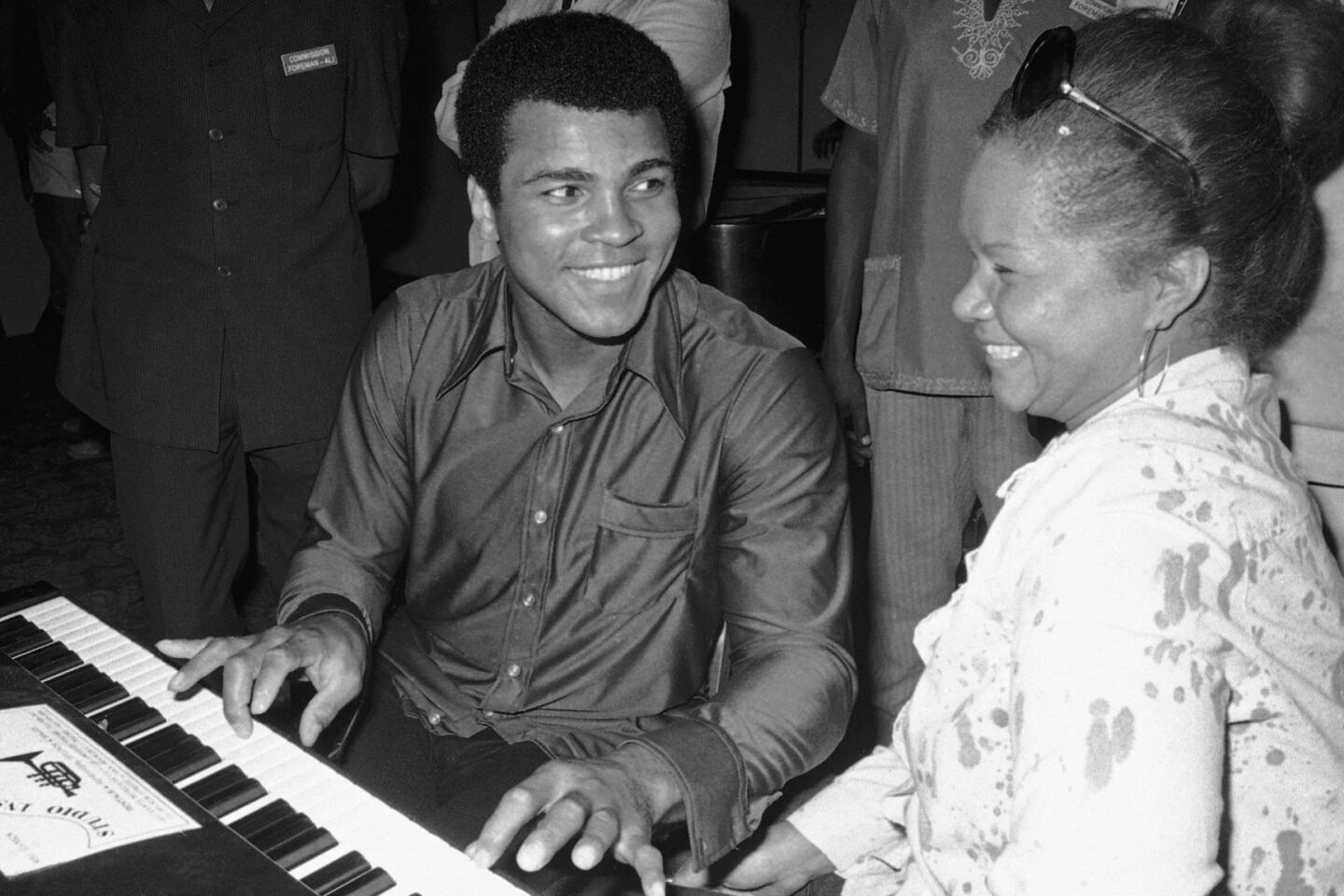

Ali gathered his wire recorder from his bedroom, found a strong, clear station on the radio playing rock ’n’ roll and recorded about two minutes of music.

“He replayed it, the music came out loud and clear and he was thrilled to pieces,” Caplan said.

“I’m going to get me one of those!” Ali told Caplan.

Ali then asked Caplan why he was at the gym.

“I’m a salesman, but I want to get into publicity,” said Caplan, whose first publicist’s job ended up being for his boyhood hero, former heavyweight champion Joe Louis.

“Oh, you want to be a boxing publicist?” Ali asked, proceeding to bring out a huge scrapbook that Caplan said was about “eight inches thick and as big as a coffee table.”

“I’ll show you about publicity,” said Ali, displaying stories on him from Sports Illustrated and Sport Magazine covers, along with the Los Angeles Times and other newspapers.

Said Caplan: “It was overwhelming that he had that many clippings so early in his career.”

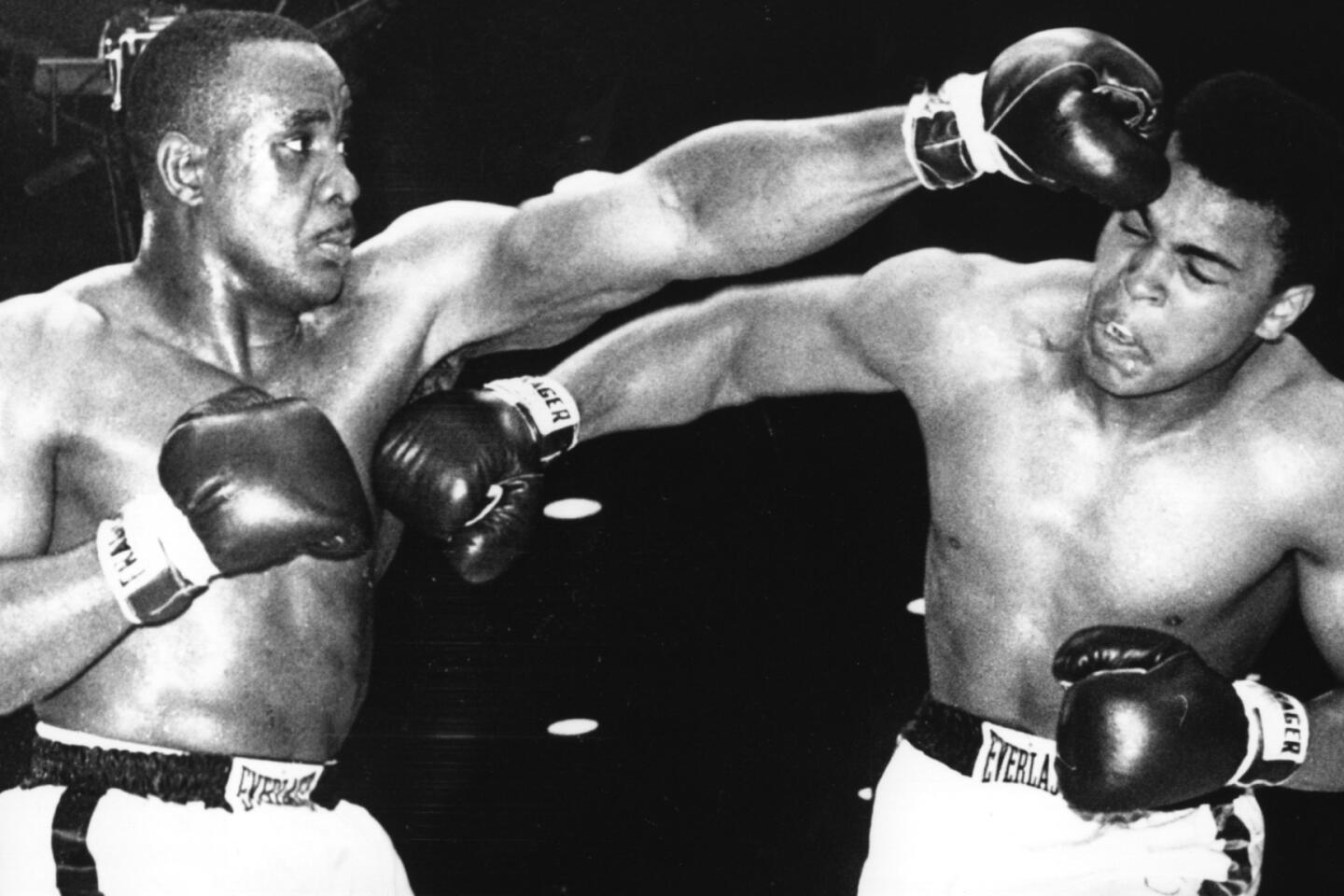

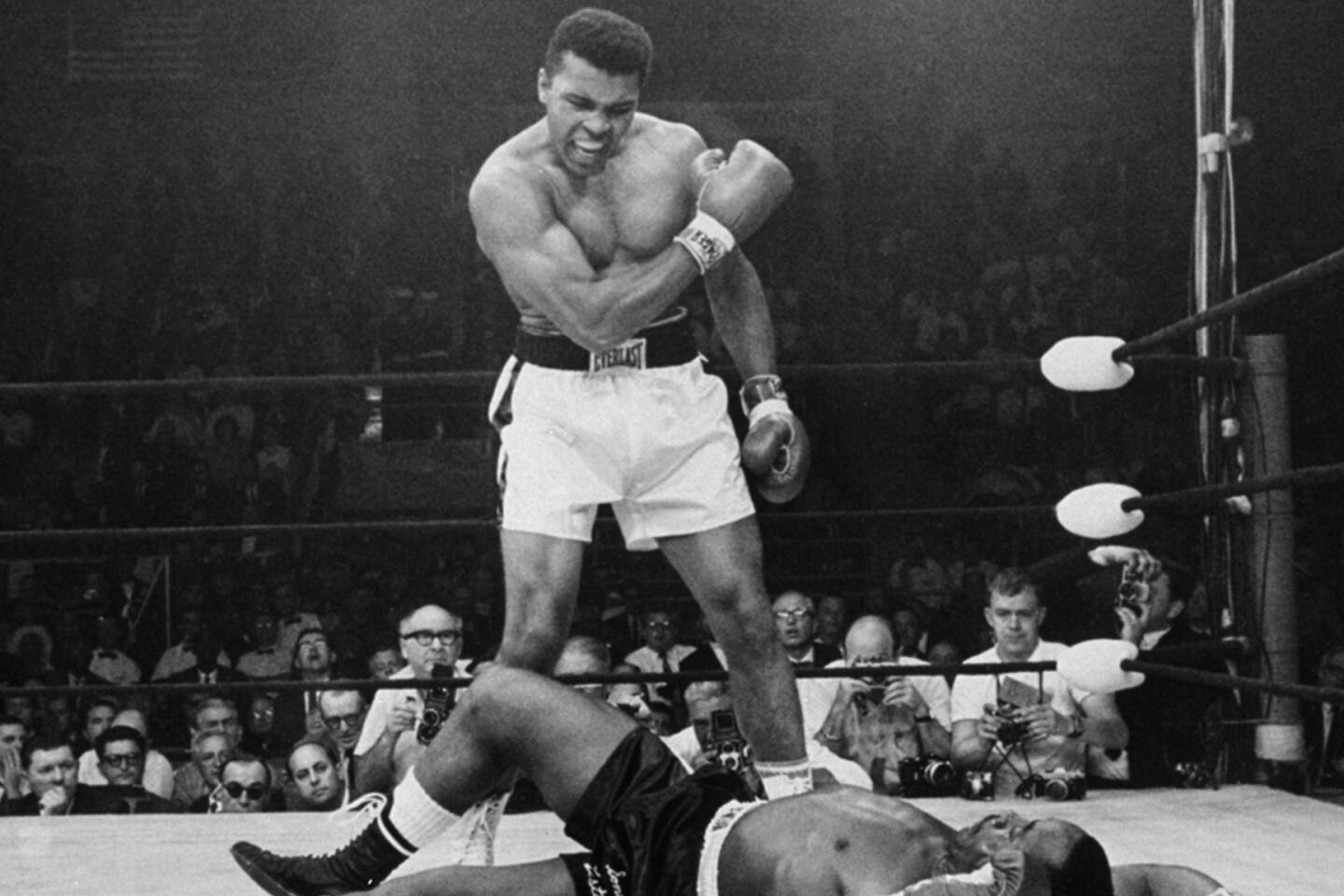

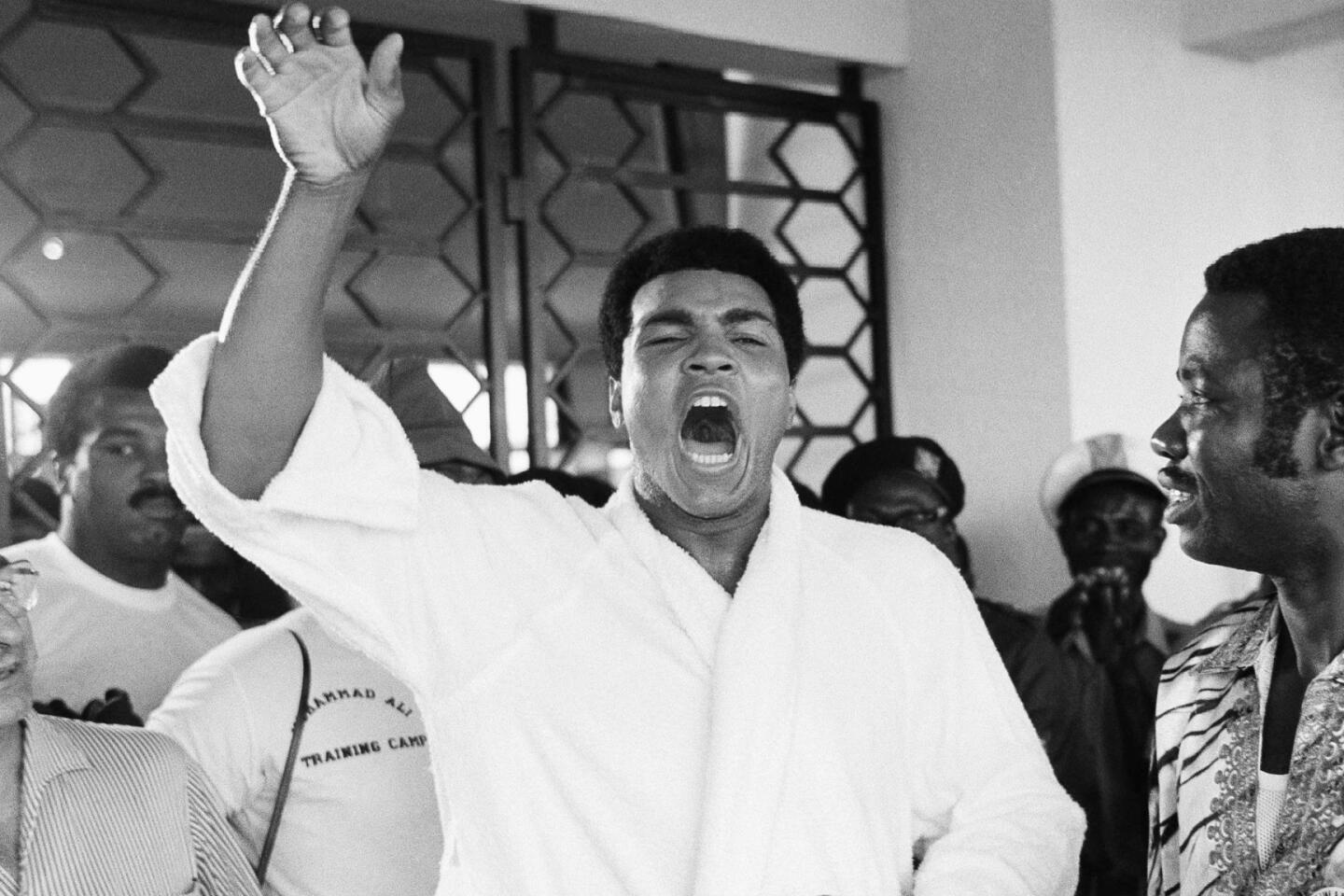

Days later, on April 23, 1962, Ali scored a fourth-round technical knockout victory over Idaho’s George Logan en route to becoming a three-time heavyweight champion and the most iconic athlete of the 20th century.

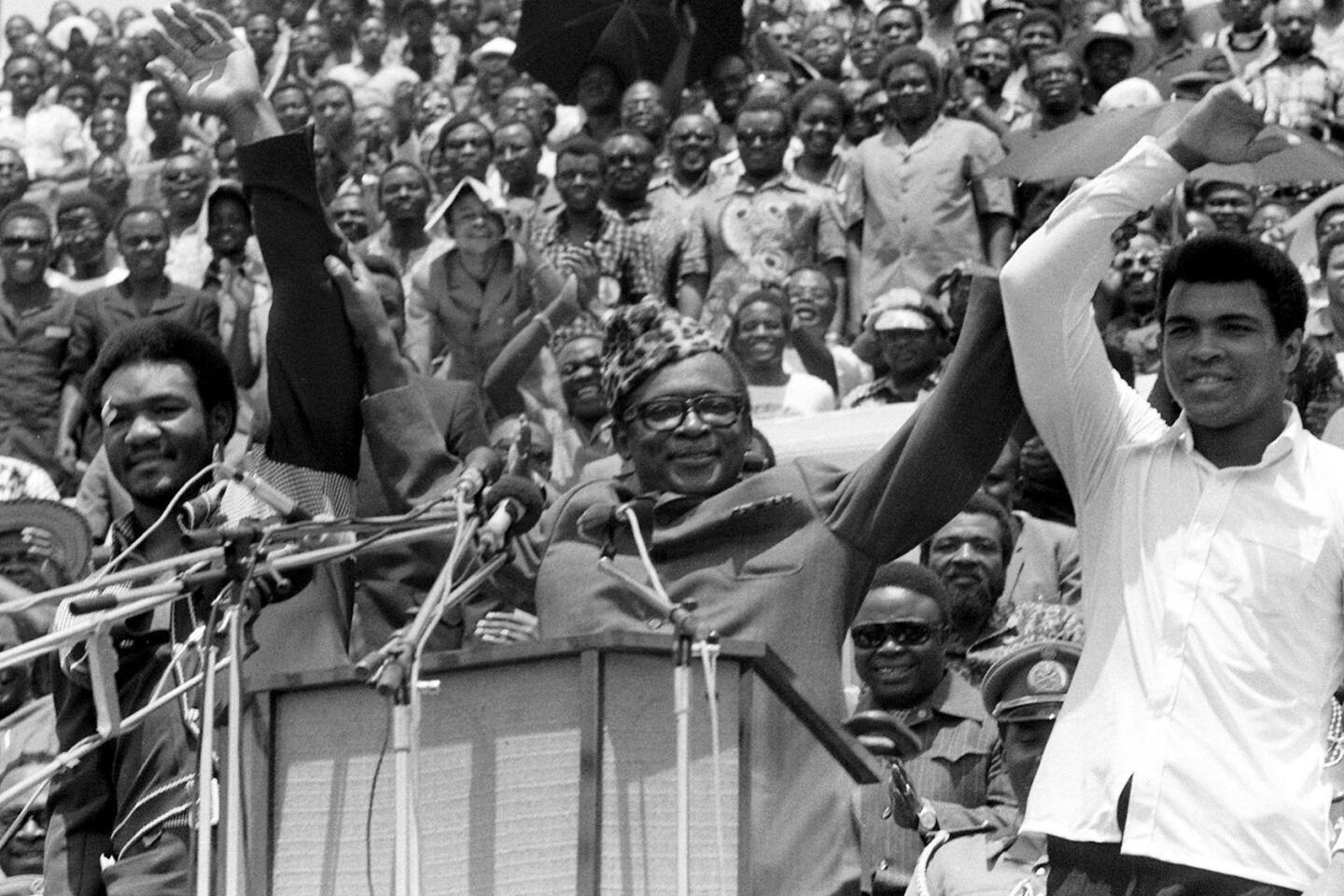

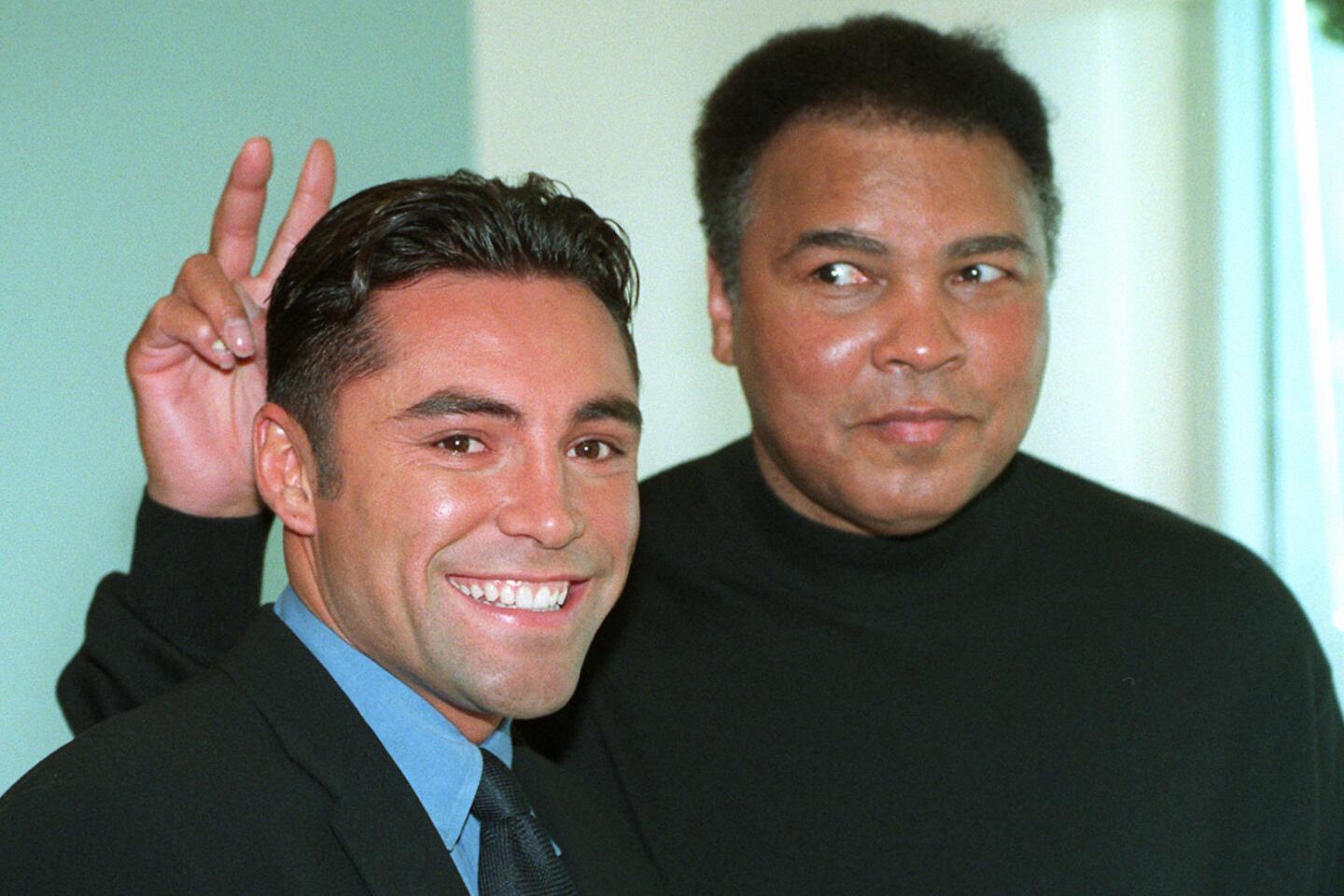

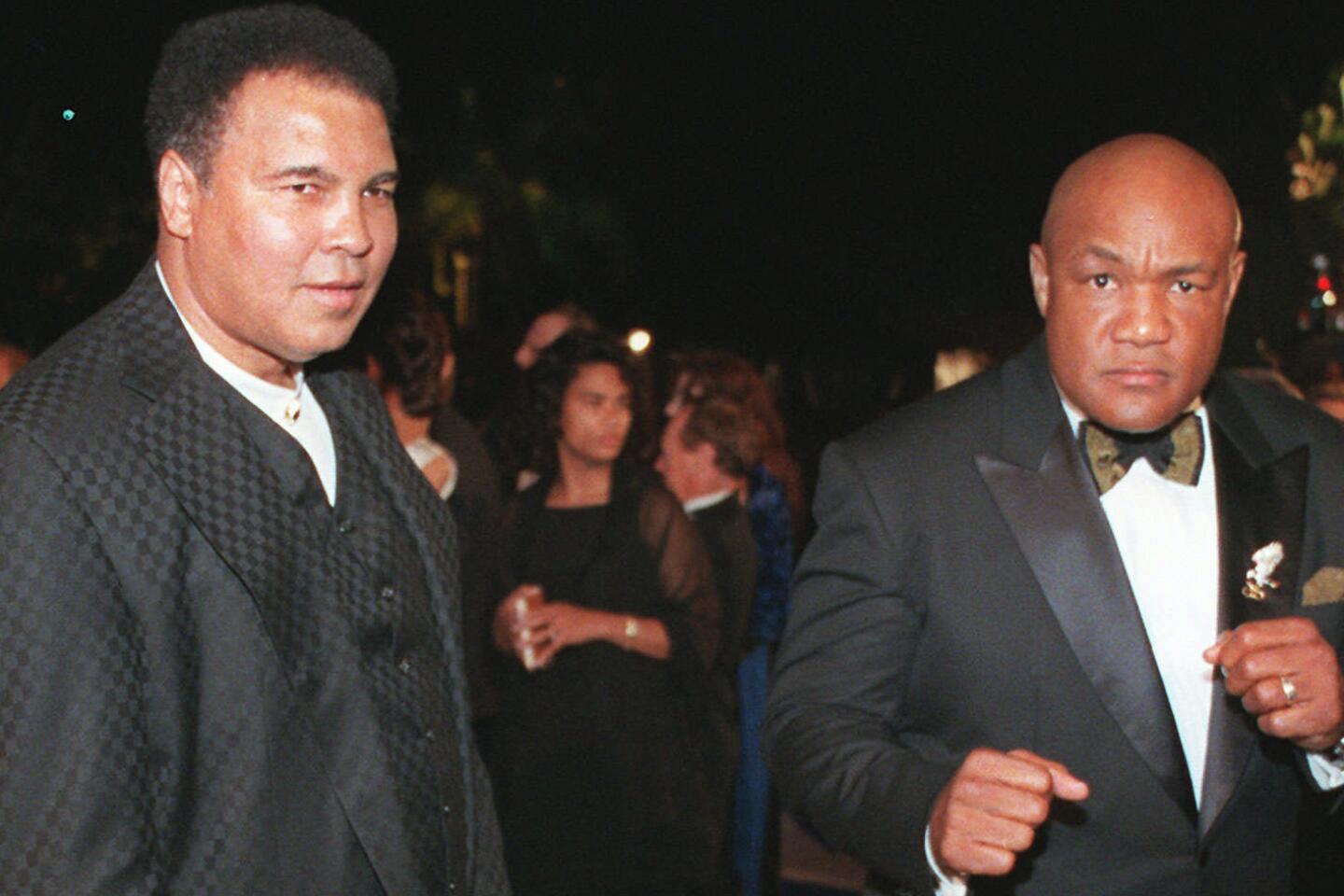

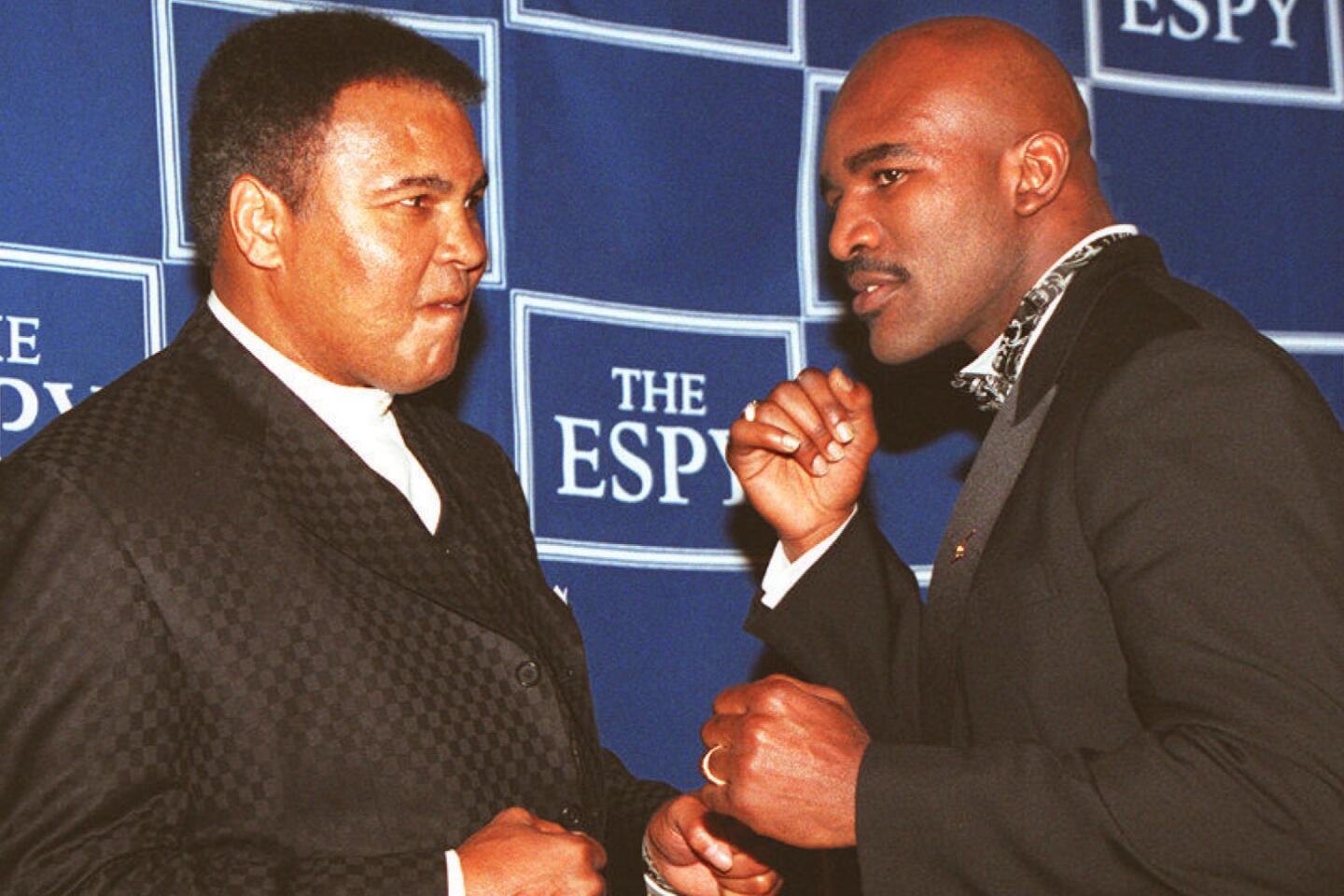

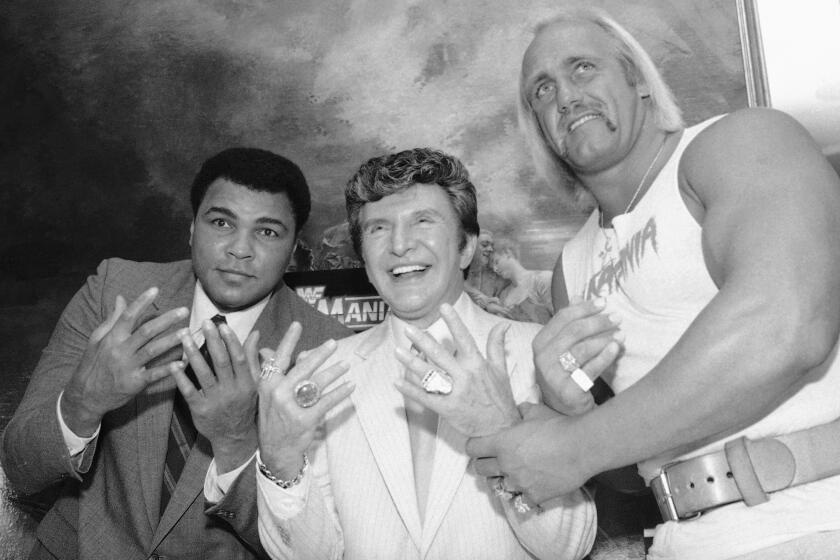

Ali and Caplan would cross paths throughout the years, including Caplan’s work with George Foreman for the 1974 “Rumble in the Jungle” against Ali.

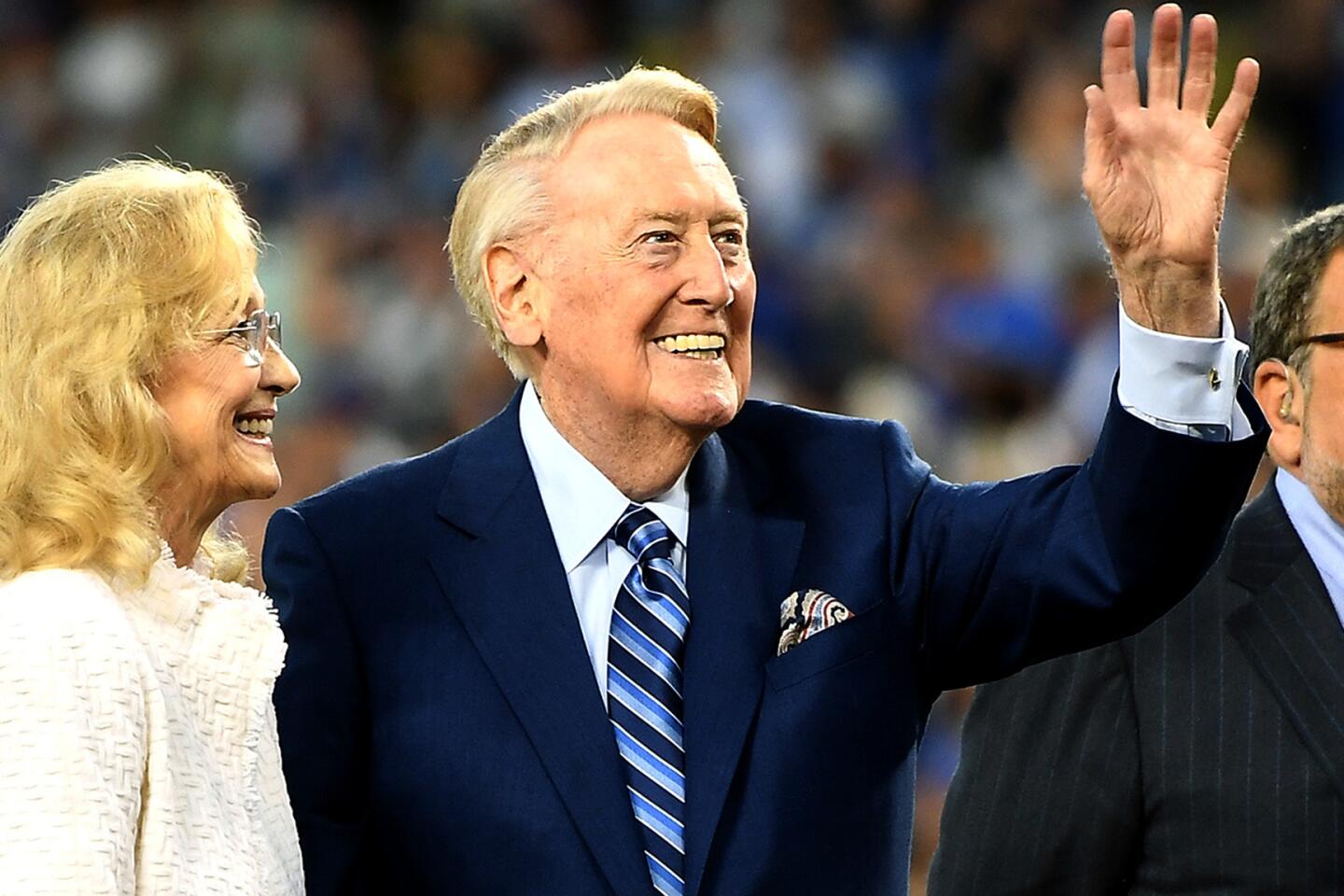

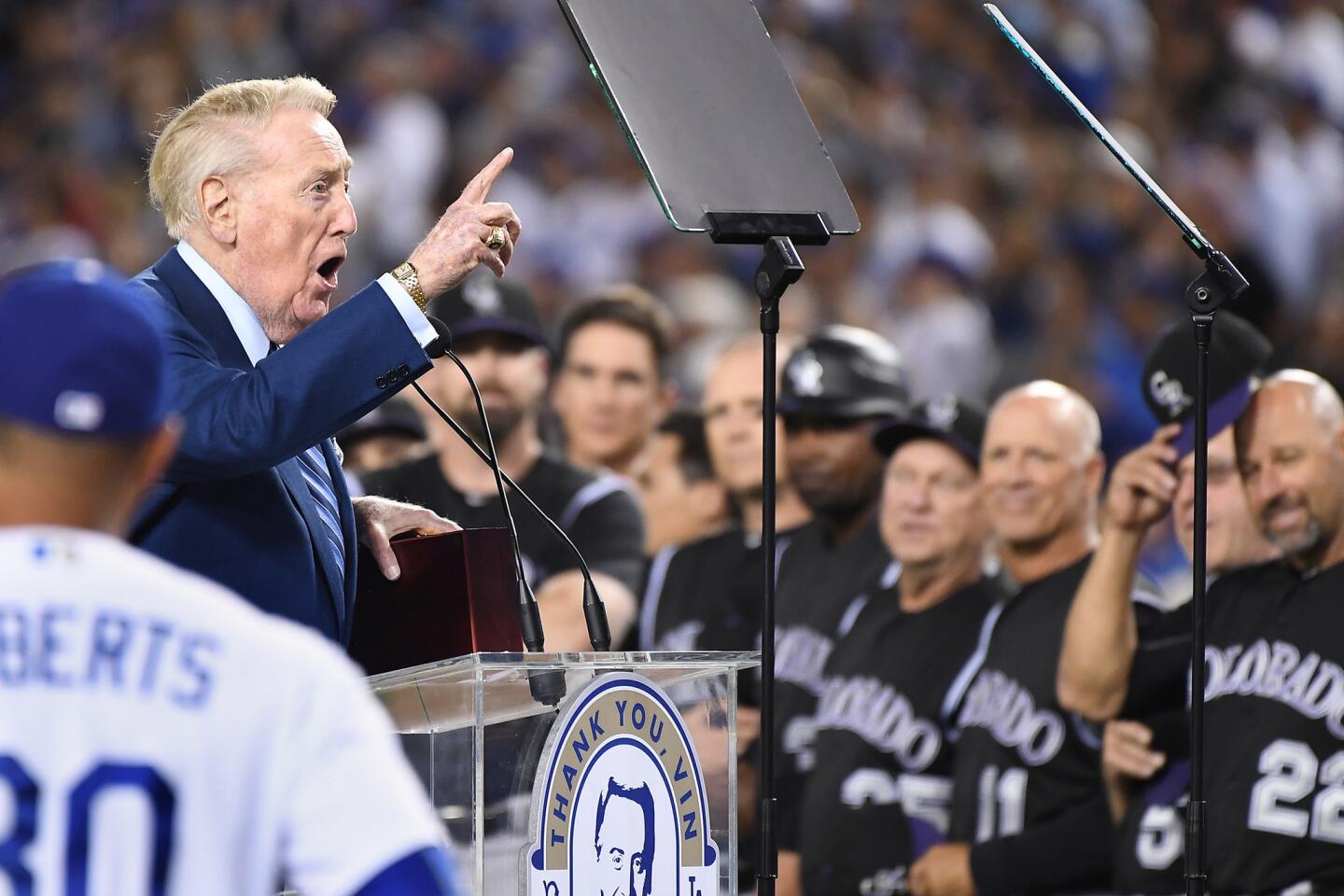

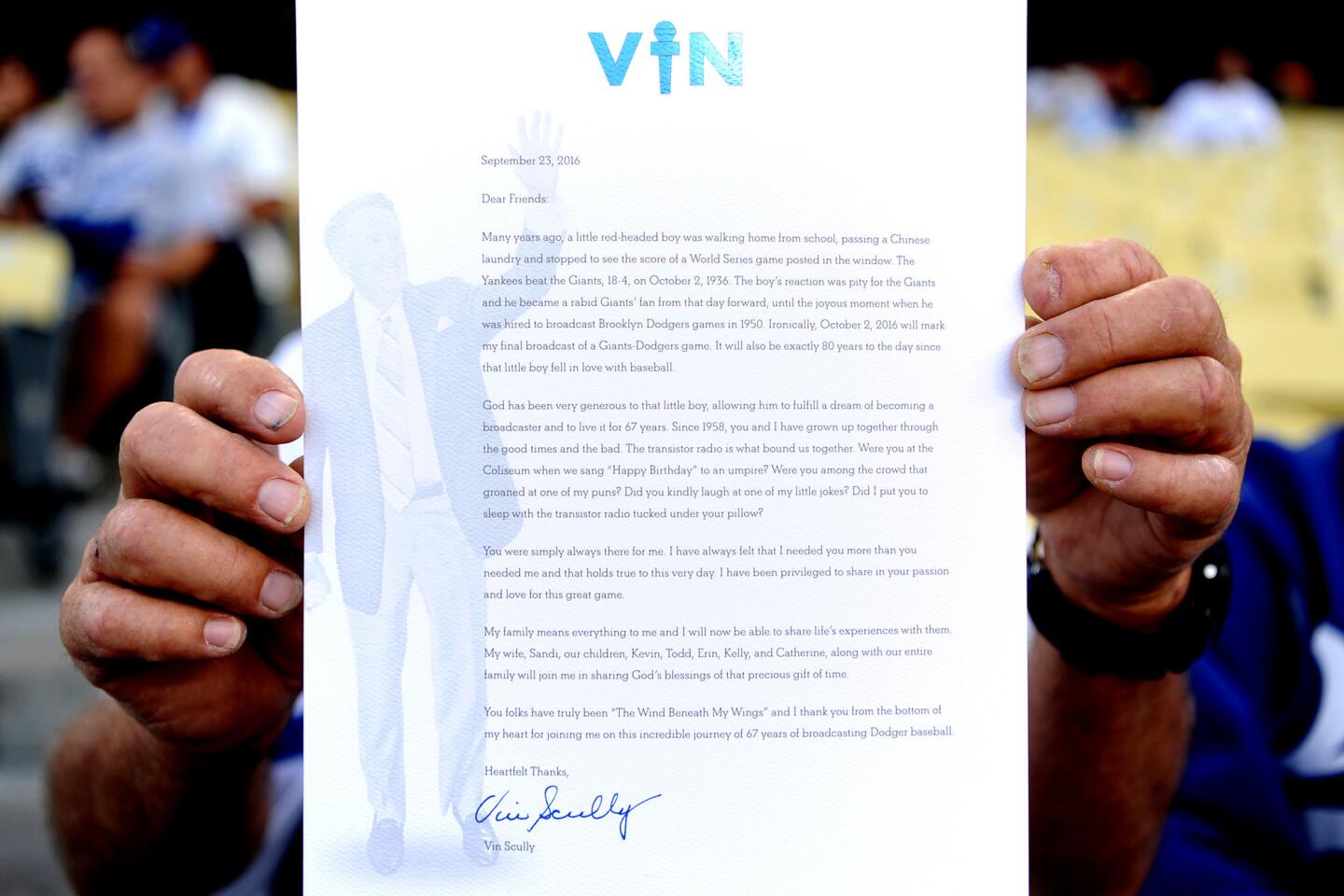

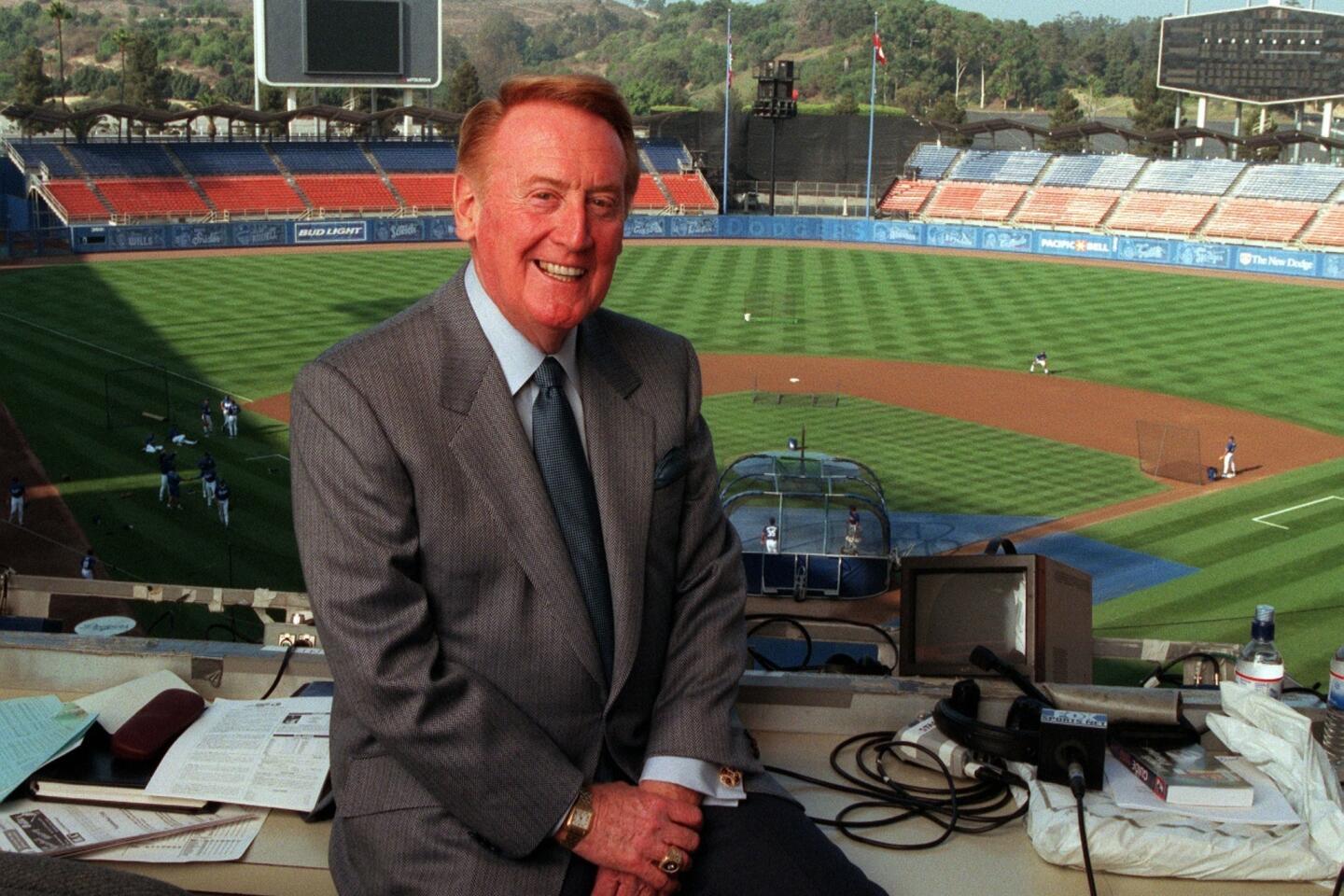

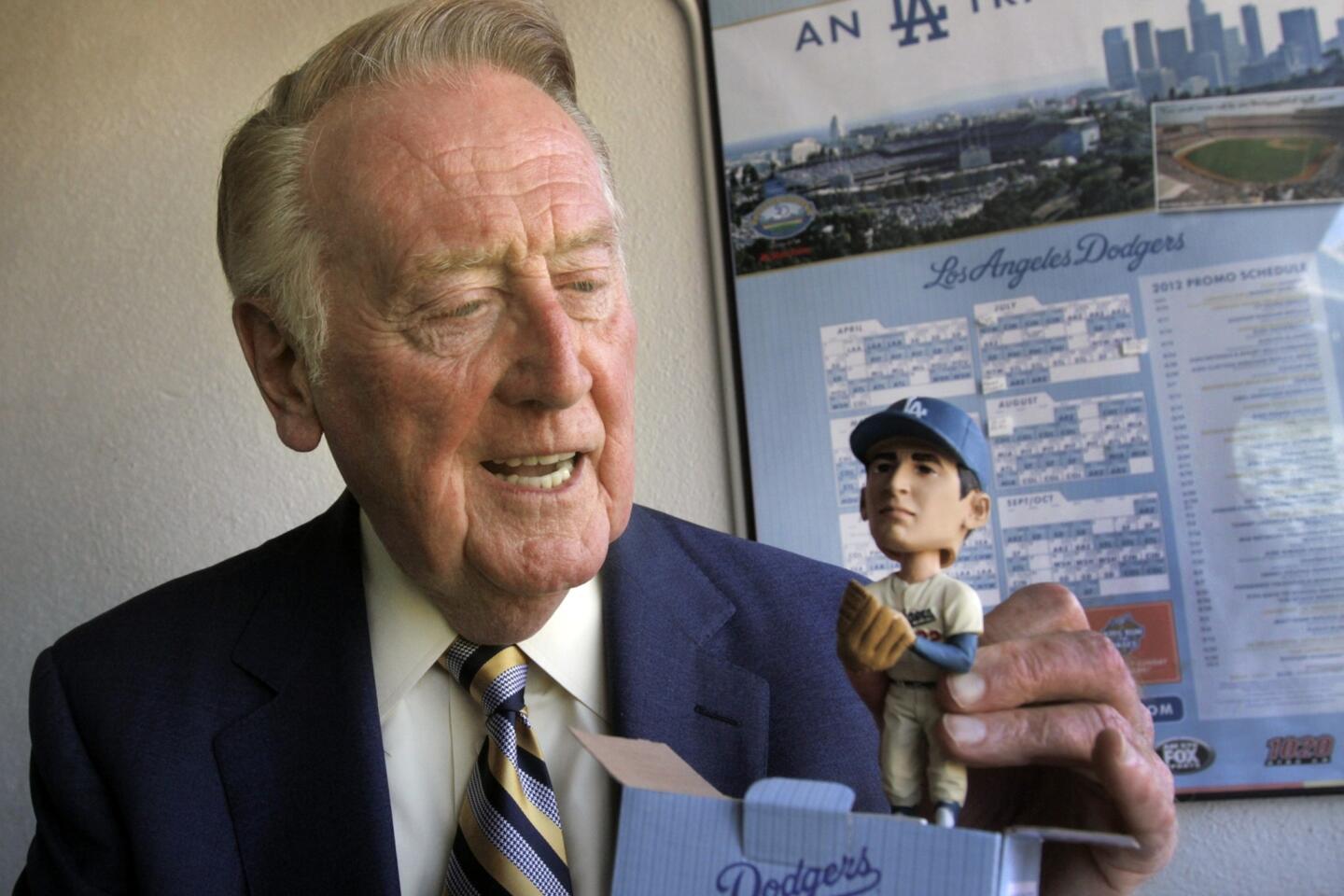

Caplan’s been transfixed by the weekend happenings with Scully, who was honored at a powerful farewell ceremony Friday at Dodger Stadium, then broadcast his final home game Sunday, when the Dodgers clinched the National League West with a walk-off home run in the 10th inning.

“A few years ago, I paid $100 for a Vin Scully baseball at a Ross Porter charity golf tournament,” Caplan said. “Vin was there and I told him my son has said to me, ‘The second most familiar male voice in my life is Vin Scully’s.’

“Vin said in a very humble, modest way, ‘You’d be surprised how many people have told me that.’”

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.