O’Bannon vs. NCAA: Judge weighing class-action certification

For the last few years, the powers that be in college sports have watched nervously as an antitrust lawsuit wends its way through federal court.

O’Bannon vs. NCAA is challenging traditional notions of amateurism, arguing that young athletes should receive more than just scholarships for their role in what has become a multibillion-dollar enterprise.

On Thursday, the case arrives at a crucial fork in the road.

A Northern California judge must decide if thousands of current and former college players can join as plaintiffs in what would become a class-action suit. That could set the stage for a massive judgment, potentially changing the business of Saturday afternoon football games and March Madness.

“It’s a very big deal,” said Michael McCann, a law professor at the University of New Hampshire. “This could be an instrumental lawsuit in terms of reshaping college sports.”

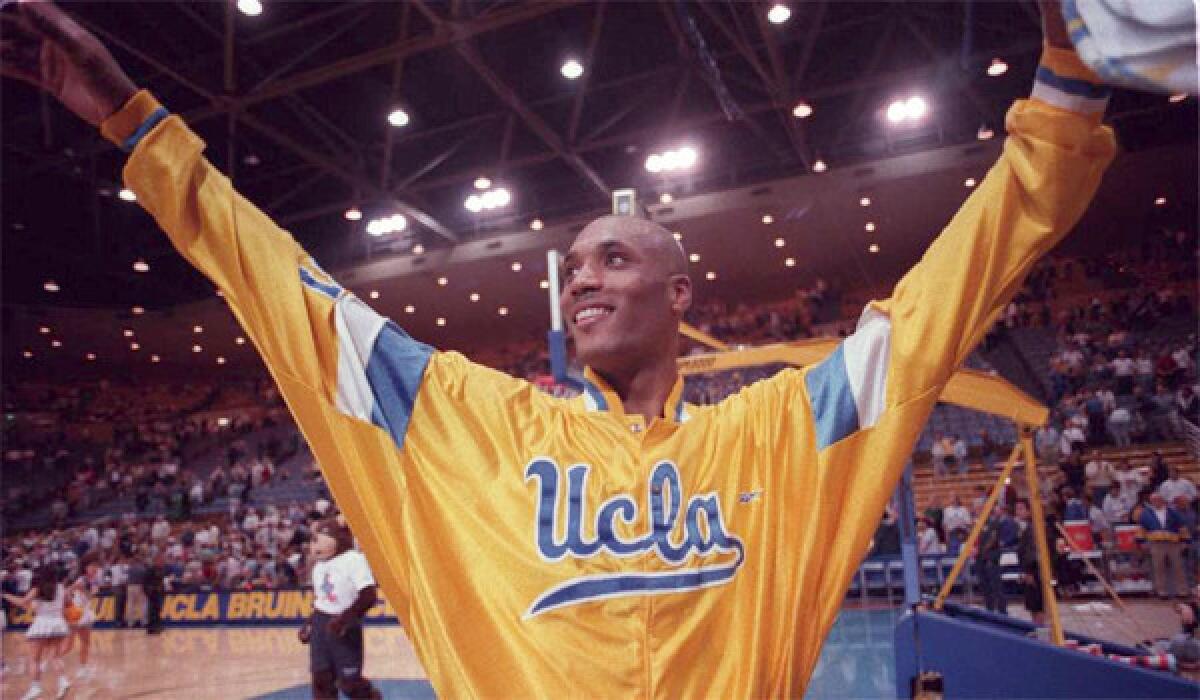

The case — spearheaded by former UCLA basketball player Ed O’Bannon — focuses on the way the NCAA and its business partners profit by using athletes’ names and likenesses in video games, photographs, promotions and, potentially, television broadcasts. The plaintiffs want a cut.

College sports leaders say they need the riches derived from football and men’s basketball to support less-popular sports. Big Ten Conference Commissioner Jim Delany filed a legal declaration stating that changes to the current system might force his member schools to “downsize the scope, breadth and activity of their athletic programs,” shifting to a model that resembles the smaller, less glamorous Division III.

But not everyone agrees with this doomsday prediction.

Some experts believe there is enough money to spread around. And a longtime critic of college sports wonders if giving athletes a larger share might help curtail what she sees as out-of-control spending on coaching salaries and training facilities.

“The perception that college athletics as we know them would be destroyed is an overreaction,” said Ellen Staurowsky, a sport management professor at Drexel University in Philadelphia. “This could be a clarifying moment.”

It was unclear whether Judge Claudia Wilken would hear oral arguments or render a decision during the certification hearing Thursday.

The case before her is a consolidation of suits filed by O’Bannon and former Nebraska quarterback Sam Keller. Others, such as basketball greats Oscar Robertson and Bill Russell, have joined in.

The plaintiffs are represented by Michael Hausfeld, famous for negotiating a large antitrust settlement with Microsoft. Attorney Ken Feinberg, who played a role in financial settlements for the BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, is also involved.

The O’Bannon suit originally focused on the use of former athlete likenesses in video games licensed by the NCAA and sold by EA Sports. The Collegiate Licensing Co., which represents nearly 200 colleges, the Heisman Trophy and the NCAA, was named too.

“I saw a kid playing a video game that had my likeness, and I thought that was wrong,” said O’Bannon, who now lives in Nevada, working at a car dealership and coaching high school basketball. “I thought that a change needed to be made.”

His legal challenge soon broadened, seeking to include current athletes and bringing television into the mix. TV money dwarfs video-game revenue, which has been estimated at less than $10 million a year.

By comparison, the NCAA has an 11-year, $10.8-billion contract with CBS Sports and Turner Broadcasting to televise its men’s basketball tournament. The Pac-12 has a $3-billion deal with Fox and ESPN, characteristic of the wealth that conferences amass by offering replays of classic games and other broadcast content.

“The NCAA is clearly worried,” said Robert Orr, a North Carolina attorney who has represented athletes, including former UCLA player Shabazz Muhammad. “You can see the PR campaign they are mounting.”

The dispute has focused on several issues: use of likenesses, a waiver that student-athletes must sign and the potential effects of revenue sharing.

Last year, NCAA executive vice president and general counsel Donald Remy issued a statement saying: “The simple, straightforward truth is that the NCAA has never licensed student-athlete likenesses.”

It is true that games such as EA Sports’ “NCAA Football” do not feature names or faces of players. But the plaintiffs say they have discovered internal NCAA emails suggesting that EA uses attributes and jersey numbers of famous players in its games.

The 2011 version of the game offers numerous examples. USC’s quarterback wears No. 7, just as Matt Barkley did that season. Louisiana State has a black quarterback wearing No. 9, just like Jordan Jefferson. Oregon State’s running back is No. 1, just like Jacquizz Rodgers the previous season.

Division I athletes must sign a waiver at the beginning of each school year to become eligible. It grants the NCAA, conferences and schools permission to use their names and likenesses “to promote NCAA championships or other NCAA events, activities and programs.”

“These are 17-year-old kids who will sign anything a school puts in front of them,” Orr said. “They don’t have a lawyer there. No businessperson in his right mind would enter into that kind of contract.”

Legal experts say athletes differ from other scholarship students who face no limitations on using their talents to earn money while in school. Music students can perform for pay and science students can take summer internships in laboratories.

If athletes were to receive a portion of the television money they help generate, college sports could be irreparably harmed, according to a series of written statements filed with the court by Delany and other college and conference executives.

Not only would revenue sharing siphon dollars away from sports such as soccer, tennis and gymnastics, it might also preclude athletic departments from maintaining women’s teams in compliance with Title IX, the critics say.

Another issue comes into play.

“I don’t think student-athletes should be paid for what they do,” said Harvey Perlman, chancellor at the University of Nebraska and a former member of the NCAA board of directors. “That is a wage, and it is inconsistent with the mission of higher education.”

If O’Bannon and his fellow plaintiffs prevail, the court would have to fit athletes into a potentially intricate financial model.

How many athletes would be reimbursed and how? Would the star quarterback, whose image appears on a video-game box, receive more than his left tackle? What about the linebacker shown making a tackle in a television special about last year’s top running back — does he get compensation?

The NCAA might also have to devise a way of compensating current players while maintaining a sense of amateurism. Some have suggested a trust fund that distributes monies after athletes have left school.

“It would be complex, but it would be solvable,” McCann said. “We’ve solved more complex things in this world.”

Such a system could affect each school differently. A recent USA Today study showed that sports programs at nine universities — including Texas, Ohio State and Alabama — generated more than $100 million during a recent school year. Many other schools had athletic budgets a fraction of that amount.

As a sport management professor at the University of Michigan, Rod Fort has studied athletic departments nationwide and believes that most could adjust.

“College sports would not change one iota,” Fort said. “It would mean that Nick Saban can’t make $5 million to coach Alabama. He can make $3 million.”

There is another possibility: Programs that attract the best recruits would probably incur the greatest revenue-sharing costs. That could serve as a luxury tax, leveling the playing field — in a small way — for the haves and have-nots.

“There is a way to make this system work,” Staurowsky said. “It’s simply a matter of distributing resources in a more appropriate way.”

Of course, not all of the potential impacts would be measured in dollars and cents.

College sports promote the romantic idea that unpaid athletes compete solely for the love of the game. At least some fans have clung to this notion, even if it requires a willing suspension of disbelief.

Would those fans like college sports less if players were being openly compensated? On the flip side, might revenue sharing keep some athletes from leaving school early to turn professional?

Perlman would like to see a compromise, with scholarships expanded to include living costs. As for selling athlete likenesses for video games, he says: “I have real questions in my mind as to whether the NCAA should be involved in that kind of activity.”

If O’Bannon vs. NCAA is going to bring change, a number of questions must be answered first, beginning with the upcoming class certification hearing.

“I don’t want to make a prediction,” McCann said of the impending decision. “But it’s one of the most interesting sports cases ever.”

Many legal experts believe that if Wilken certifies the case, the NCAA would pursue a settlement that could involve a substantial amount of money but could mitigate changes to the current arrangement.

A trial could result in larger systemic changes, but getting to the courtroom could take years.

Either way, attorney Orr expects that the most important part of college sports will endure.

“It doesn’t change the games,” he said. “It doesn’t change Duke-North Carolina basketball. And it doesn’t make UCLA-Southern Cal football any less exciting.”

twitter.com/LATimesWharton

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.