Arresting developments from Neuheisel’s past

Rick Neuheisel focused his sharp, gray eyes on me. This was not the smiling Rick we’ve seen recently. This was the serious Rick, and he needed to be.

“It is what it is,” he said. “I am not going to run and hide.”

It was Tuesday afternoon and I had come to his office with questions about a recent newspaper series that reported several players on his 2000 Washington football team had blazed a trail of unchecked lawlessness.

Neuheisel was, of course, well aware of the series, published last month by the Seattle Times. While the series said at least 14 athletes from that team would eventually be accused of serious crimes, it focused on three of the most valuable -- defensive players Curtis Williams and Jeremiah Pharms, and offensive star Jerramy Stevens.

I read aloud a section of the series listing accusations against his players, including allegations of sexual assault, animal cruelty, driving drunk and domestic violence.

He grimaced.

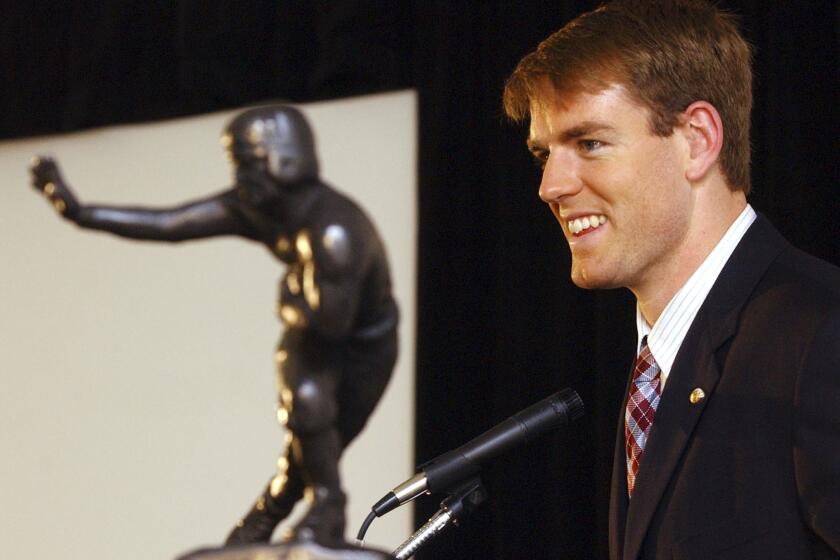

All of this was mighty uncomfortable for Neuheisel. In December, he was named coach at UCLA. He’s a hometown hero. For many, he has returned as a savior for a struggling team.

But there’s no escaping his past. Neuheisel left his last two head coaching jobs -- at Colorado and Washington -- amid a storm of allegations and findings that he’d played it loose with the rules that govern college sports.

Now he sat before me in his office, intent, focused, ready to talk -- and eager to show that he’s learned something.

For starters, though, he reminded me that some of the Seattle Times’ series focused on problems that occurred before he was at Washington. This is true, particularly so of Williams, who ended up paralyzed after a hit in a game during that 2000 season.

Neuheisel also said that when he was coach and the players in question were under investigation, he was largely kept out of the loop by prosecutors and police. That’s a fair point, too. Good prosecutors and police don’t have loose lips. Much of the detail in the investigative series involves facts that Neuheisel wouldn’t have known about unless he was James Bond.

Still, the investigation showed there were ways Neuheisel could have done a much better job of disciplining his players -- showing them there’s a price to be paid for acting like entitled prima donnas.

By failing to act decisively with one of them, Neuheisel may well have sent a troubling message to some on his team: play for the Huskies and you are above the law.

The player in question was Stevens, the Huskies’ best receiver that year.

I don’t know Stevens, who clings to a career in the NFL despite more recent troubles and was recruited to Washington by Neuheisel’s predecessor. I’ve heard that he can be extremely smart and charming. But if the Seattle Times’ investigation is to be believed, he can also be a menace.

Before arriving at Washington, Stevens reportedly had spent time in jail for smoking pot while on probation for fighting. As Neuheisel took over at Washington in 1999, he knew of Stevens’ past and hoped the 6-foot-7 tight end had turned the corner.

But months before Neuheisel’s second season, Stevens was arrested -- accused of raping a coed on an early morning outside a row of fraternities and sororities.

What happened? Not much.

There was talk of an internal university investigation into the alleged crime. It never happened.

I asked the new UCLA coach why he hadn’t pushed for one. He leaned back on his couch, looked out the window and said it just wasn’t his place. He said that after the arrest was made he met with his athletic director, and that an agreement was made to not penalize his player until more facts emerged.

The entire affair showed how prosecutors in Huskies-crazed Seattle treated the Stevens case with kid gloves. According to the Seattle Times, among several questionable moves, prosecutors never interviewed Stevens, and even turned over victim and witness statements to his legal team.

In the end, the Seattle Times reported, despite compelling DNA evidence and witness accounts, prosecutors decided not to press charges, saying the accusations could not be proved.

“What happened with Jerramy,” Neuheisel said, “is he was arrested but not charged.” That meant the team did nothing, too.

I told the coach that maybe, while prosecutors looked at the case and before they decided not to press charges, he should have suspended Stevens. These allegations were that serious.

Neuheisel rubbed his hands together and disagreed. It wouldn’t be right, he said, for a coach to suspend a player for mere accusations, no matter what they were. He’d need more evidence to make such a move, and said that at the time he just didn’t have it.

“What evidence did we have, that I was privy to?” he asked. “The stuff that was written in that article was not stuff that I was privy to.”

Stevens kept getting in trouble. The Seattle Times’ investigation showed that soon he was involved in an accident on a freeway and fled the scene.

A few months later, after the Huskies won the Rose Bowl in January 2001, he reportedly slammed his pickup truck into a retirement home and then drove off. Soon, he pleaded guilty to hit and run and received a 90-day sentence that was suspended on the condition he stay clear of trouble.

All Neuheisel did for punishment after the hit and run was sit Stevens on the bench for the first half of 2001’s opening game.

Just a half? I asked. Come on.

“Out of all of this, that’s my biggest regret,” Neuheisel said. He gave a painful look. “I should have made that penalty stiffer. I had an opportunity to send a loud and clear message and neglected to do so. I should have been stronger.”

He told me that, if he had to do it all over, he’d have taken Stevens out for at least three games.

Now, I hadn’t necessarily agreed with all of what Neuheisel had told me. He could have done more. While he was no James Bond, he was the powerful head coach of a powerful team -- he could have known more, too. But this talk of a three-game suspension? Music to my ears.

To me, the Seattle Times series shows that college coaches need to back away from their fear of disciplining players who are being investigated for serious crimes. This was a rape accusation, bad enough. What if a guy is being investigated for murder? You’re telling me he’s still going to suit up on Saturdays?

A good coach is like a parent, and any parent worth much of anything will make a kid feel the consequences of judgments poorly made.

At the least, Stevens seemed to have shown poor judgment, just for being where he was -- in public, having sex, according to the series. If coaches know a player’s past the way they should -- if there’s trouble with anger or drugs or domestic violence -- then there should be no dancing around doing what’s right and effective. Suspend such players the moment they get arrested. Don’t wait for prosecutors to press charges. So a kid has to miss playing a few football games while an investigation goes on -- big deal.

Get these kids into counseling. On game days, see to it they are studying. If the players don’t like it, tough, take away their scholarship. They need to learn some limits.

Neuheisel didn’t agree with me. He thought my solution was draconian. No surprise. Still, he said that at UCLA he’ll be tougher on his players.

“I didn’t give out huge penalties in the first place,” he said, leaning forward. But now, “I can see the value of stiff penalties in the future, when they are warranted.”

Bruins fans need to hold him to that.

--

Kurt Streeter can be reached at kurt.streeter@latimes.com. To read previous columns by Streeter, go to latimes.com/streeeter.

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.