Patriots’ rule-bending goes back decades, to ‘snow plow’ game in 1982

The New England Patriots weren’t always a NFL powerhouse. Far from it.

But for many years they have stretched the rules for the sake of winning. And that started with the infamous “snow plow game.”

In 1981, the Patriots were 2-14 and the only team to lose to the lowly Baltimore Colts — which they did twice — and ended the season with a nine-game losing streak.

They played in a place named for a low-rent beer, Schaefer Stadium, a dump with zero amenities that cost only $7 million to build in 1970 (or about $41 million in 2015 money). And it was cold. Very cold. I remember this because I worked there in high school, peddling merchandise adornedwith the Patriots’ then-hideous logo, and always sold more of the opponents’ gear.

The next season wasn’t shaping up to be much better. The NFL’s 1982 season was shortened to nine games because of a players’ strike, meaning every game held bigger consequences toward qualifying for the postseason.

By Sunday, Dec. 12, the Patriots were 2-3 and could not withstand another loss. They were to face the mighty Miami Dolphins, who would reach the Super Bowl in January.

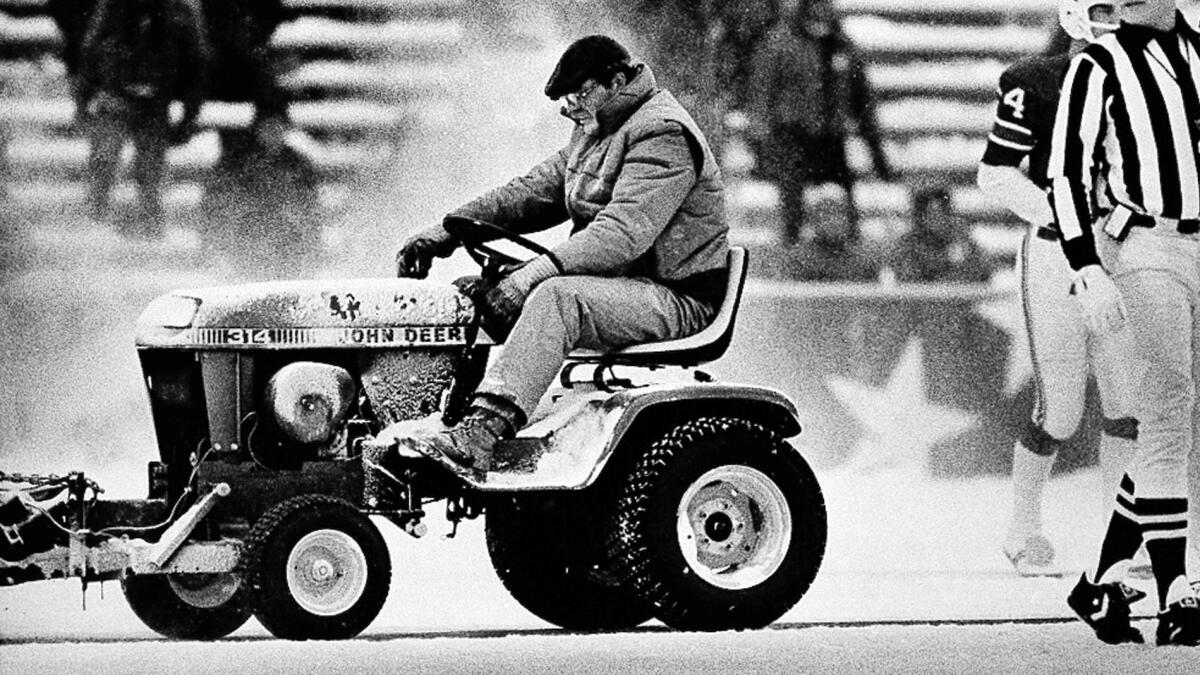

The night before the game, Schaefer Stadium’s artificial-turf field was iced over by frozen rain. And shortly before the game started, a heavy blanket of snow descended. An emergency plan was made by the officials to allow a sweeper — it was reported as a snow plow, but it was actually a tractor equipped with a sweeper attached to the front — to clear the field at 10-yard intervals during breaks in the action.

Just 25,716 people showed up to watch — low even for the terrible Patriots but a testament to the team’s hardscrabble days, when Tom Brady was in kindergarten.

With 4 minutes 45 seconds left in the fourth quarter, the score was 0-0. But the Patriots drove down to the Dolphins’ 16-yard line. Facing fourth down, they had a chance to put three points on the board and took it.

As the field-goal unit came on, a man named Mark Henderson drove the sweeper onto the field. But instead of sweeping only the 20-yard line, Henderson veered three yards wide, across the 23, where Matt Cavanaugh would hold the ball for placekicker John Smith.

Dolphins coach Don Shula threw a fit, but his pleas to stop the play were disregarded by game officials. The ball was snapped, caught by Cavanaugh, and held in place for the left-footed Smith to kick it through the uprights for a 3-0 Patriots lead.

And that was the final score.

“I think it’s the most unfair thing I’ve ever been associated with in coaching,” Shula later said. “It’s the most unsportsmanlike act that I’ve ever been around.”

Henderson, a convicted burglar on work release from the nearby prison, Massachusetts Correctional Institute-Norfolk, became an instant celebrity. The Patriots praised Henderson’s move — for which the NFL would create a rule to prevent its happening again — and awarded him a game ball.

Interviewed years later, Henderson jokingly said of his actions, “What are they gonna do, throw me in jail?”

The Dolphins exacted revenge, 28-13, in the playoffs a few weeks later, but that did little to dampen the Patriots’ season highlight.

The tractor, a John Deere 314, and its snow attachment hang in an exhibit in the team’s museum.

Schaefer Stadium was later destroyed to make way for Gillette Stadium, a top-tier venue. And the Patriots have played in seven Super Bowls, winning three, with another opportunity on Sunday.

Whatever happens, you can bet the Patriots will do whatever it takes to win. It’s a celebrated part of their history.

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.