Road for female wrestlers is often filled with prejudice and misunderstanding

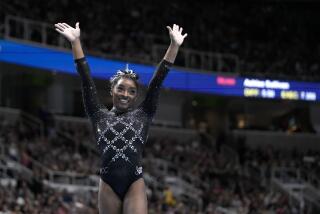

The first time Adeline Gray stepped onto a wrestling mat, she was 6 years old and her long hair wasn’t the only thing that distinguished her from all the boys in the gym.

“I wore leotards that were pink and purple,” she said. “And I put on these shoes that were colored with a marker to make them girlier.”

No one raised a fuss about her joining a traditionally male sport — it simply wasn’t a big deal for little boys and girls to wrestle each other.

But Gray’s path to the Olympics — she ranks as a gold-medal favorite in Rio de Janeiro this summer — hit a roadblock several years later when she encountered an obstacle all-too-common for female wrestlers:

High school.

“Your bodies change and you start getting self-conscious about wearing these spandex suits,” she recalls. “That’s when people start to notice.”

It’s a lot bigger than just wrestling on the boys team. It’s about women living out an athletic dream and getting to do something amazing with their lives.

— Adeline Gray

Coaches and parents make nasty comments. Male opponents get squeamish or forfeit in protest. It can be discouraging for a teenage athlete looking for the toughest competition she can get.

“It’s a critical time for females in our sport,” said Terry Steiner, the U.S. Olympic women’s coach. “All of a sudden, there are people thinking they don’t want that kind of contact between boys and girls.”

The problem is numbers: Women’s wrestling wasn’t added to the Olympics until 2004 and is still a relatively small sport in this country, with an estimated 11,500 participants at the high school level.

So there aren’t enough girls to wrestle only against girls; to get regular competition, they must go against boys.

Growing up in Colorado, Gray was an oddity on the club team coached by her uncle. The same was true for Helen Maroulis, another top U.S. Olympian, in her Maryland town.

Still, they were both encouraged by early success against boys.

“Girls are a little more physically developed at the younger level,” said Mike Moyer, executive director of the National Wrestling Coaches Assn. “It takes a while for the boys to catch up.”

The talent usually evens out in high school, where the sport also becomes more serious. Difficulties that arise for female wrestlers often fall into three categories, beginning with parents.

People began muttering negative comments about Maroulis in the stands. She could ignore them but her mother and father could not, urging her to quit.

It wasn’t until the Olympics added women’s wrestling that they could see a future for their daughter in the sport.

“I almost lost what I love the most,” she said.

Coaching is another challenge.

The overwhelming majority of coaches are male and they must take a hands-on approach to the job, grappling with their athletes to demonstrate technique. Steiner struggled with this when he switched from men’s wrestling to overseeing the women’s national team.

“There are a lot of places I touch someone on the wrestling mat that I would never touch them off the mat,” he said. “With a female, you worry about doing something wrong.”

Athletes are the final piece of the puzzle. Gray hit her first substantial resistance when she made varsity as a freshman at a high school with a strong wrestling program.

Some teammates quietly resented her presence, she said. The coach — who also happened to be her guidance counselor — stepped in.

“Women are going to be allowed on this mat,” she recalls him telling the team. “You’re going to treat them as athletes.”

Not everyone agreed. Some wrestlers from other schools forfeited their matches rather than face a girl.

“It hurt for those boys not to give me any respect,” she said. “My parents would tell me ‘You got a bye this round, just keep going.’ ”

All of this can be daunting for young women already dealing with teenage years. Gray and Maroulis said their love of wrestling pulled them through.

Both ended up at a U.S. Olympic training site in Michigan where they could get elite-level coaching and wrestle for a nearby high school. Gray progressed to the national team while Maroulis competed for Simon Fraser University in Canada.

As defending world champions in their weight classes, the women no longer face questions about their place in the sport. And now they have female wrestlers to practice and compete against at the international level.

Wrestling officials hope the women’s side of the sport will come to be viewed in the same light as martial arts such as karate and judo, where gender is not as much of an issue. They would like to believe things are improving.

Seven states now hold girls’ high school championships and more than 30 colleges field women’s teams.

Still, Gray hears horror stories when teaching at junior camps.

One young wrestler, she says, was forced to cut her hair short by a high school coach trying to discourage her from trying out for the team.

“Thank God this girl had the cutest face and could rock a pixie cut,” Gray said. “But it really broke my heart to know there are people still fighting to keep women out of combat sports.”

That kind of resistance provides even more incentive for her and Maroulis. They believe a pair of gold medals in Rio might further legitimize their sport.

“It’s a lot bigger than just wrestling on the boys team,” Gray said. “It’s about women living out an athletic dream and getting to do something amazing with their lives.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.