1968: ‘Game of the Century’ changed college basketball, for better and worse

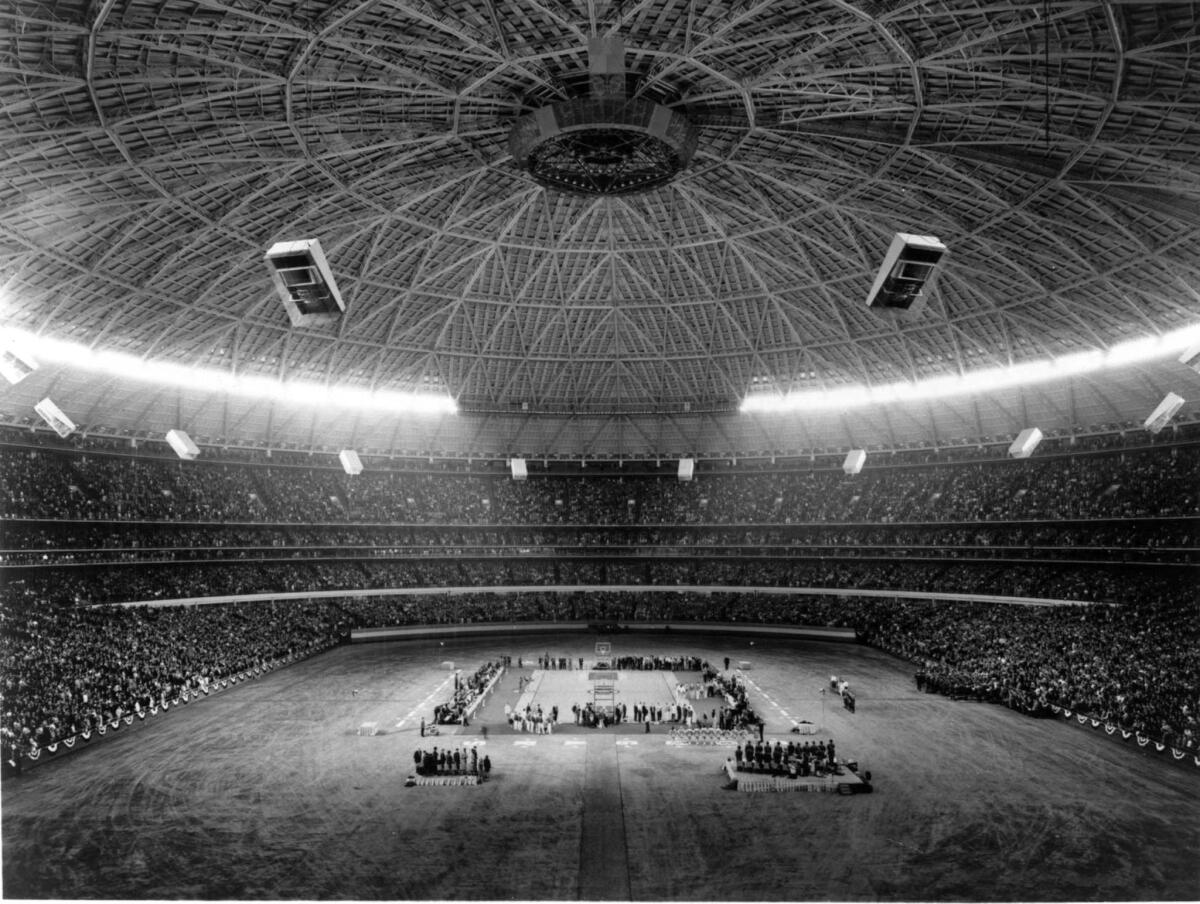

The borrowed basketball court seemed overwhelmed by the climate-controlled palace of concrete and steel.

Nicknamed the Eighth Wonder of the World, the Houston Astrodome had already hosted a president, two dozen astronauts and, more recently, a demolition derby before the court arrived in two moving vans in late January 1968.

The space-age dome packed with foam-padded seats in a kaleidoscope of colors hadn’t hosted an event quite like the showdown between UCLA and Houston.

For weeks, advertisements in Houston touted the meeting between the country’s top-ranked teams as the “Game of the Century.” The dome’s trademark AstroTurf had been rolled up. Workers pieced together 225 sections of the 22,000-pound court on loan from the Los Angeles Sports Arena. It sat alone in the middle of the sprawling dirt floor, illuminated by more than 1,000 floodlights.

“The whole setting is so garishly spectacular, if unreal,” Jeff Prugh wrote in The Los Angeles Times, “that probably not even Warner Bros. or Cecil B. DeMille could have dreamed of it.”

Fifty years later, the questions surrounding the game have faded. Would Lew Alcindor, later known as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, play for UCLA after suffering a scratched left cornea eight days earlier? Could a dome designed for baseball and football work for basketball? How many viewers would tune in for the first regular-season college basketball game broadcast nationally in prime time? Would UCLA’s 47-game win streak continue?

The game transformed college basketball from a regional to national sport, opened the way for multibillion-dollar television contracts to broadcast March Madness and helped spark the long-running debate over whether athletes should share in the windfall.

“This game unmasked the commercial appeal of college sports and really stripped away much of the remaining innocence about college sports being amateur and pure,” said B. David Ridpath, president of The Drake Group, which advocates for academic and financial responsibility in college athletics. “The facade was easier to keep back then but ... the game looked more professional than college at that point.”

The late Dick Enberg, UCLA’s broadcaster, provided play by play from an 18-inch deep trench near the court for 120 television stations in 49 states. He said he believed it was the most important sporting event he broadcast.

“[The game] was absolutely critical in catapulting college basketball to the level of popularity we know today,” Enberg wrote in his memoir ‘Oh My!’

Organizers faced a basic problem before the history making night. The three major television networks didn’t want to broadcast the game. Eventually Eddie Einhorn, who became president of the Chicago White Sox years later, paid $27,000 to syndicate the game through TV Sports Inc. He pitched stations in person to carry the game, author Ron Rapoport recalled in “How March Became Madness,” and convinced scores of them to cancel regular programming to clear space for the spectacle.

Though showing a college basketball game to a national audience hardly seems revolutionary 50 years later, Einhorn’s gamble created a sensation.

“It is throbbing with mystery and intrigue,” columnist Don Page wrote in The Times before the game. “No matter what transpires, watching 50,000 fans watching 10 giants bouncing a ball in the Astrodome is worth the price of flipping on the TV dial. It kind of makes you forget it’s only a game.”

The move to television didn’t please UCLA coach John Wooden.

“The television people won’t like hearing me say it, but I said it before so I’ll say it again: I think television is one of the worst things that ever happened to intercollegiate basketball,” he told The Times in 1998. “It’s made showmen out of the players and that hurts team play. And it means that there are games played every day of the week at any time of day.”

A bigger issue loomed for Wooden in the days before the game. Alcindor, already the subject of frenzied speculation about a professional career, suffered from vertical double vision and impaired depth perception after his eye was scratched against Cal eight days earlier.

He missed two games, confined to the Jules Stein Eye Clinic at UCLA much of the time. His conditioning suffered. His status remained in doubt and Wooden later said he gave Alcindor the option to sit out against Houston.

“Now a scratched eyeball may not be much of a problem for a guitar player or a well digger, but it’s a disaster for a basketball player,” Alcindor wrote in Sports Illustrated in 1969. “The whole game is based on depth perception and visibility and when one of your eyes is giving you two blurred images instead of one clear one, you might as well stay in bed and turn the job over to somebody else.”

The star didn’t stay in bed — which happened to be a custom 10-foot model at the team hotel with “Big Lew” written on it.

Twenty million viewers tuned in for the game. The largest crowd to watch college basketball at the time — 52,693 people — filled the dome in seats that ranged from $2 to $5. The best ones were 100 feet from the court. Some used binoculars or opera glasses.

“There were dazzling lights and thundering cheers that swirled inside the cavernous arena and a fireworks-spewing, cartoon-flashing scoreboard that looked almost as big as the LBJ Ranch,” Prugh and Dwight Chapin wrote in “The Wizard of Westwood.”

Einhorn sat in the trench next to Enberg and took calls in the first half from advertisers purchasing spots for the second half.

The Astrolite animated scoreboard flashed the attendance: “Largest paid crowd to see a basketball game anywhere in the world ... ever!!!”

Alcindor played all 40 minutes but didn’t resemble the best player in the country. He made just four of 18 shots, one of his worst performances at UCLA, and managed 15 points. Meanwhile, Houston’s Elvin Hayes rolled up 39 points, including two free throws with 28 seconds left to give the Cougars a 71-69 victory. Hundreds of fans rushed across the ring of dirt to celebrate on the court.

“This was the most fantastic basketball game ever conceived by the human mind,” columnist Wells Twombly wrote in the Houston Chronicle.

The day after, Wooden second-guessed his decision to play Alcindor.

“I think I handled the situation rather poorly,” Wooden told reporters.

The schools split $200,000 in revenue from the game — about $1.5 million in present-day value — minus a 17% cut for the Astrodome.

Even as UCLA and Houston cashed in and proved nationally televised basketball games could compete in prime time, the NCAA worried about the spiraling costs of college athletics. Newspaper stories warned of a “financial crisis” and “sky-rocketing cost” and schools investing in “giant, modern athletic complexes costing millions.”

“These are not luxuries, but necessities,” an NCAA spokesman told reporters at the time.

One Times columnist suggested Alcindor needed to thank UCLA for a “free education.” Robert Maynard Hutchins, the former president of the University of Chicago, proposed athletes skip college and immediately start professional careers.

“The industrialization of athletes at a university is almost identical with the industrialization of any other process that goes on in the commercial world,” Hutchins said six months after the game. “Not interested in educating these young people, not interested in what happens to them after they graduate, all you want to do is make as much money, get as much publicity as possible.”

Times columnist Jim Murray criticized the entire system.

“Do YOU care whether UCLA wins the NCAA? Do I? Should society?” he wrote. “How much longer do we woo these young popinjays in sneakers, water-walkers in shoulder pads, till they lose all perspective of where they really fit in the grand scheme of things?”

One Yucaipa man wrote to The Times in response: “I have yet to hear an acceptable justification of the place of ‘big-time’ athletics in an educational program.”

A year after the game, NBC paid $500,000 to broadcast the NCAA tournament, which was then comprised of 25 teams. The tournament expanded — reaching 64 teams in 1985; 68 in 2011 — and revenue grew exponentially. The NCAA is in the midst of a $10.8-billion deal with CBS and Turner that runs through 2024 and, two years ago, agreed on a $8.8-billion extension over seven years.

“Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone and [Einhorn] invented college basketball on television,” Enberg said in “How March Became Madness.”

Two months after the game, UCLA and Houston met in an NCAA tournament semifinal at the Sports Arena. In his locker, Alcindor kept the Sports Illustrated cover with a picture of Hayes shooting over him in the January loss. The extra motivation wasn’t needed. Alcindor delivered 19 points and 18 rebounds as UCLA destroyed Houston 101-69 en route to winning the championship.

“Anybody with eyes in his head,” Alcindor wrote in Sports Illustrated, “could see how much better we were than Houston.”

Twitter: @nathanfenno

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.