Dazzling, then they disappear

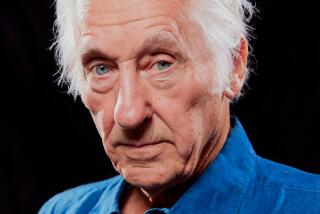

Last February, Andy Goldsworthy was working on a massive stone sculpture on the grounds of Church Brough school in Cumbria County, in northwestern England. Goldsworthy, an environmental artist popularly known for the 2001 documentary about his work, “Rivers and Tides,” has spent his life crafting shapely things from found materials — leaves, stems, thorns, earth, stones, icicles, snow — near his home in southern Scotland.

That day as he trimmed one rough-hewn stone after another to build a cone shape, he paused to look up with delight at snow drifts making white patterns in a gully high on Warcop Fell, and he remarked on how the drifts were shrinking day by day, becoming ever more elegant and linear, dividing into segments.

Just as the snow, the steep hillside and the temperature cooperate to make a beautiful image, so Goldsworthy himself works — learning how snow and ice melt and cling, crack and taper, accepting these properties and easing them into new forms.

Of working in winter, he has written, “I can touch North in the cold shadow of a mountain, the green side of a tree, the mossy side of a rock .”

The work requires inexhaustible inventiveness, patience and the sheer hardihood to craft freezing materials out in the open, sometimes through the night, and it is not without risk: “I hate wearing glasses . I am always wanting to take them off and have to stop myself because of the danger of getting snow blindness.”

One of his classic ice works — and the first I saw — is a starburst made of icicles. He dipped their ends in snow, then water and held them in position till they knitted together to make a form like a glittering, spiny sea urchin come to land.

Goldsworthy first worked with ice when he was a gardener a few miles north of Cumbria County in 1981, at a place where the Swindale Beck river cuts through a deep valley. “It was freezing cold down there all day,” he said. “Perfect for making ice works.”

In his work, icicles jut horizontally out of dry stone walls as though they were silvery javelins driven through the wall from the far side. Ice walls, stacked in a style he learned from the Inuit, are carved so thin that light glows through a lattice of shimmering white circles.

Goldsworthy relishes the harsh conditions and cunningly adapts to them. In the creation of some pieces, he sometimes has to prop up the various components, as they fuse, with wooden sticks that he then detaches by breathing or urinating on them.

At the same time as his feet and fingers suffer from the cold, he’s thinking with the utmost subtlety about the implications of his work. His language is often imaginatively physical.

Of a work made of icicles, bent and joined to make a gleaming spiral like a spring coiled round a tree trunk, he writes that the ice expresses “the core of the tree, its spine as if for a moment that spine has shifted and stepped outside the tree, almost as an apparition.”

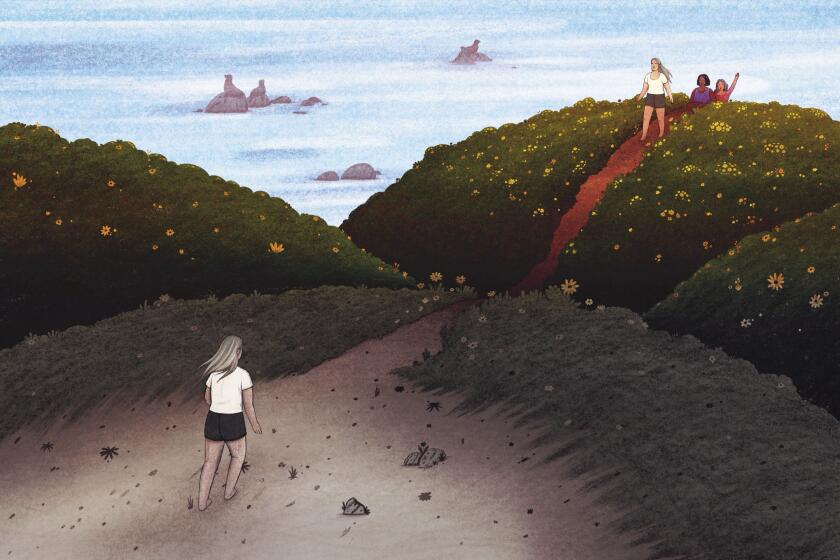

At other times his language defines fundamental values. In winter 1989, when he was about to go and make snow works at the North Pole, he wrote: “It belongs to no one — it is the Earth’s common — an ever changing landscape in which whatever I make will soon disappear.”

Sometimes I try to make Goldsworthy-like works. The beauty of a circular vessel is that if the water in it freezes, then thaws, a perfect disc of ice floats free. When this happens in our birdbath, I pose the disc in the crotch of a tree or on a stone and photograph it, like a full moon of silver come to Earth. Once I did this with a massive disc, a yard across and 2 inches thick,from a water cask at an olive farmer’s shelter in the Tuscan Alps. When I posed it on the rim of an ancient warlord’s tower nearby, it shone like a steel targe.

*

Craig is the author most recently of “The Glens of Silence: Landscapes of the Highland Clearances.” He and Andy Goldsworthy cowrote “Arch” in 1999.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.