A sound check along the Memphis-to-Nashville ‘Music Highway’

Memphis, Tenn.

Knowing how obsessed Elvis fans can be, I wasn’t surprised when my wife and I drove up to the Heartbreak Hotel and found, true to the song’s lyrics, that it was actually “down at the end of Lonely Street” and that the desk clerk was “dressed in black.”

Our room was lined with photos of the King, and two TV channels were devoted 24/7 to Elvis Presley’s music and movies. And, as expected, the souvenir shop contained such Elvis novelties as “Love Me Tender” tea sets and copies of the work shirt that a teenage Presley wore when he drove a truck for Crown Electric. (Guess which one I bought.)

But one thing that did surprise me on this, the first night of our five-day Memphis and Nashville music tour, was the Elvis look-alike chatting it up in the lobby. You might expect an official greeter in a Vegas skyscraper but hardly at a modest, 128-room place like this.

It wasn’t until I saw him chowing down on biscuits and gravy at the complimentary breakfast the next morning that I realized the laugh was on me. The guy wasn’t a hotel employee but another guest, which brings us back to the point about obsessed Elvis fans.

More than 50,000 of them are expected to flock to Memphis for Elvis Week, which runs Aug. 11 to 19. Besides a candlelight vigil at Graceland marking the 30th anniversary of Presley’s death, a concert at the FedExForum will feature members of his Vegas band playing live while Elvis performs via video on a giant screen.

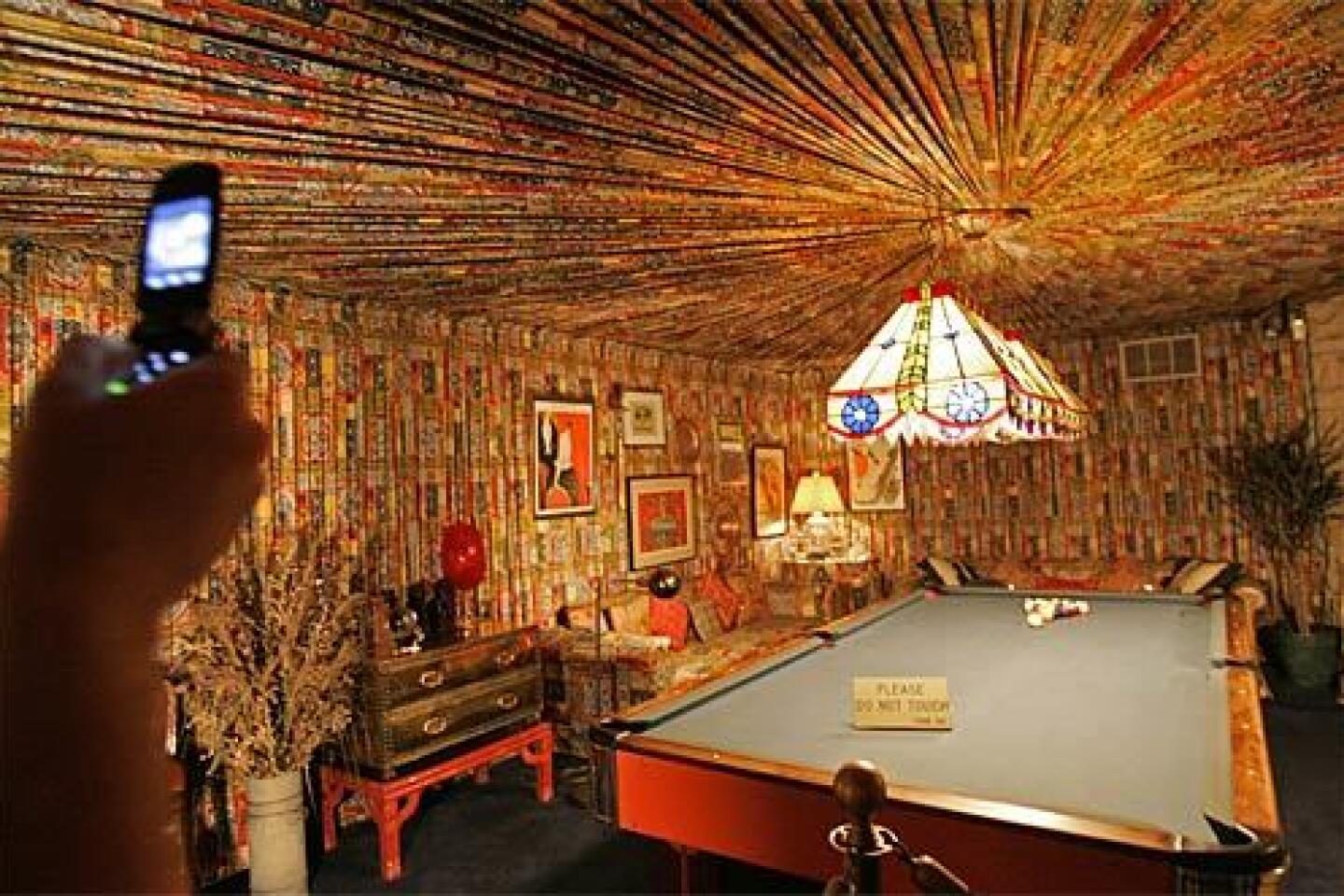

But you don’t have to wait until Elvis Week to get a dose of the King. He rules here year-round. For $100, at one of the official souvenir shops across from Graceland (Elvis’ home), you can play pool on the same table that Presley and the Beatles used during their meeting in L.A. in 1965. And just 15 minutes away at the Arcade cafe, you can have one of Elvis’ beloved peanut butter and banana sandwiches. Fried, of course.

Once you get past the carnival atmosphere, you can find an inspiring story in the music history of Memphis and Nashville, linked by Interstate 40 — the “Music Highway.” Thanks to nearly a dozen museums and historical sites, there is no richer, more illuminating showcase of musical roots in the country than in this 220-mile stretch of highway.

And we’re talking more than simply the land of Elvis. The region’s heritage also includes such landmark figures as Hank Williams, Otis Redding, Patsy Cline and Al Green.

When you follow the music trail through Tennessee, including a visit to the National Civil Rights Museum, you realize that the music was part of a wider social and cultural revolution that involved race, class and politics.

Whether you’re just after good-time nostalgia or pop-culture history, the trip is a joyful, illuminating experience.

But health-conscious pop fans, beware. I swore I would eat only one bite of that fried peanut butter and banana sandwich, but I didn’t count on it being soooo good. I ended up using half my day’s calorie allotment on just six bites.

Funny. Years ago, I used to count my pennies on vacations. Now it’s calories.

On to Graceland

Elvis may have been rock’s greatest star, but I wouldn’t want him decorating my house. Graceland’s living room, with its 15-foot-long white sofa, is tasteful enough in a formal ‘50s way, and the black baby grand piano adds a nice touch to the music room.But brace yourself before entering the den. The jungle theme, complete with a waterfall and an overload of wooden exotica, may have reminded Elvis of relaxed times in Hawaii, but the décor is more likely to remind visitors of dated scenes from a tacky ‘60s comedy. I felt dizzy after seeing the wildly conflicting patterns on the multicolored drapes covering the billiard-room ceiling and walls.

While touring the Colonial Revival-style structure, which attracts 600,000 visitors a year, you’ll see lots of Elvis’ personal items as well as gold records and colorful jumpsuits from the Vegas years. Yet there’s a more affecting side of Graceland: the rags-to-riches saga of the young man from the housing projects buying the home of his dreams, partly for his financially struggling parents.

Looking at the garden (where he now rests) and the horses in the pasture, you understand how the property was a source of pride and a sanctuary.

Figure on spending three to four hours at Graceland, the various museums and the souvenir shops, but skip the restaurants. There are better choices, including Neely’s, a family barbecue operation, and, of course, the Arcade cafe.

For some reason, those chunky peanut butter and banana sandwiches, which come with 2 pounds of steak fries, aren’t on the menu at the informal Arcade; you have to ask for them. Cross your fingers when you do, because they’re only available when the bananas are ripe.

Next stop: Sun Records and, for rock fans, guaranteed goose bumps.

Heart and soul

It’s easy to miss the Sun Studio as you head down Union Avenue toward downtown because it’s in an ordinary, two-story brick structure that sits at an angle. Just start looking for tourists with cameras when you approach the 700 block of Union.The entrance to the museum is actually in an adjacent cafe where Sun owner Sam Phillips relaxed or held business meetings between recording duties. Sit in one of the booths, and you can imagine a young Johnny Cash telling you all about this song he’s just written about a prison out in California.

The tour starts upstairs in a room detailing the history of the studio, which specialized in blues artists, including Ike Turner and Howlin’ Wolf, before Phillips found Presley. But the heart of the tour is the 18-by-32-foot studio, pretty much untouched since the ‘50s.

For me, in fact, the Memphis trip turned from Elvis fun to musical legacy when I looked at the tape on the floor marking the spot where the 19-year-old singer stood the night in 1954 he recorded “That’s All Right,” the single that largely defined rock ‘n’ roll as we know it today. The Sun guide also told us that Jerry Lee Lewis recorded “Whole Lot of Shakin’ Goin’ On” in one take with the same primitive equipment, a reminder that great music is based more on imagination and passion than on technology and polish.

The sense of musical mission was equally strong at our next stop, the home of Stax Records, whose ‘60s and ‘70s glory days are saluted in a run-down stretch of McLemore Avenue. This museum, with more than 2,000 artifacts, is much larger than the Sun site. It’s also easy to spot, thanks to a large theater marquee.

Stax’s focus, oddly enough, was country and pop until co-founder Jim Stewart moved to the mostly African American neighborhood on McLemore, where he converted an old movie theater into a studio and record shop. Not only did Stewart start stocking albums his customers requested, which meant R&B and soul, but he also began making records to appeal to those customers.

Stax’s classic sound was a gritty, Southern-fried R&B and funk served up by such artists as Redding, Isaac Hayes and the Staple Singers. The label folded in 1975 and the original building was razed. The new facility opened in 2003, and it conveys well the early spirit of brotherhood among the black and white artists at the label.

If the Sun and Stax tours focus on what happened inside studios, two other essential museums in Memphis tell you about high-impact cultural and historical factors outside the studio.

Start downtown with the Rock ‘n’ Soul Museum, across from the Gibson Guitar Factory (which offers yet another tour).

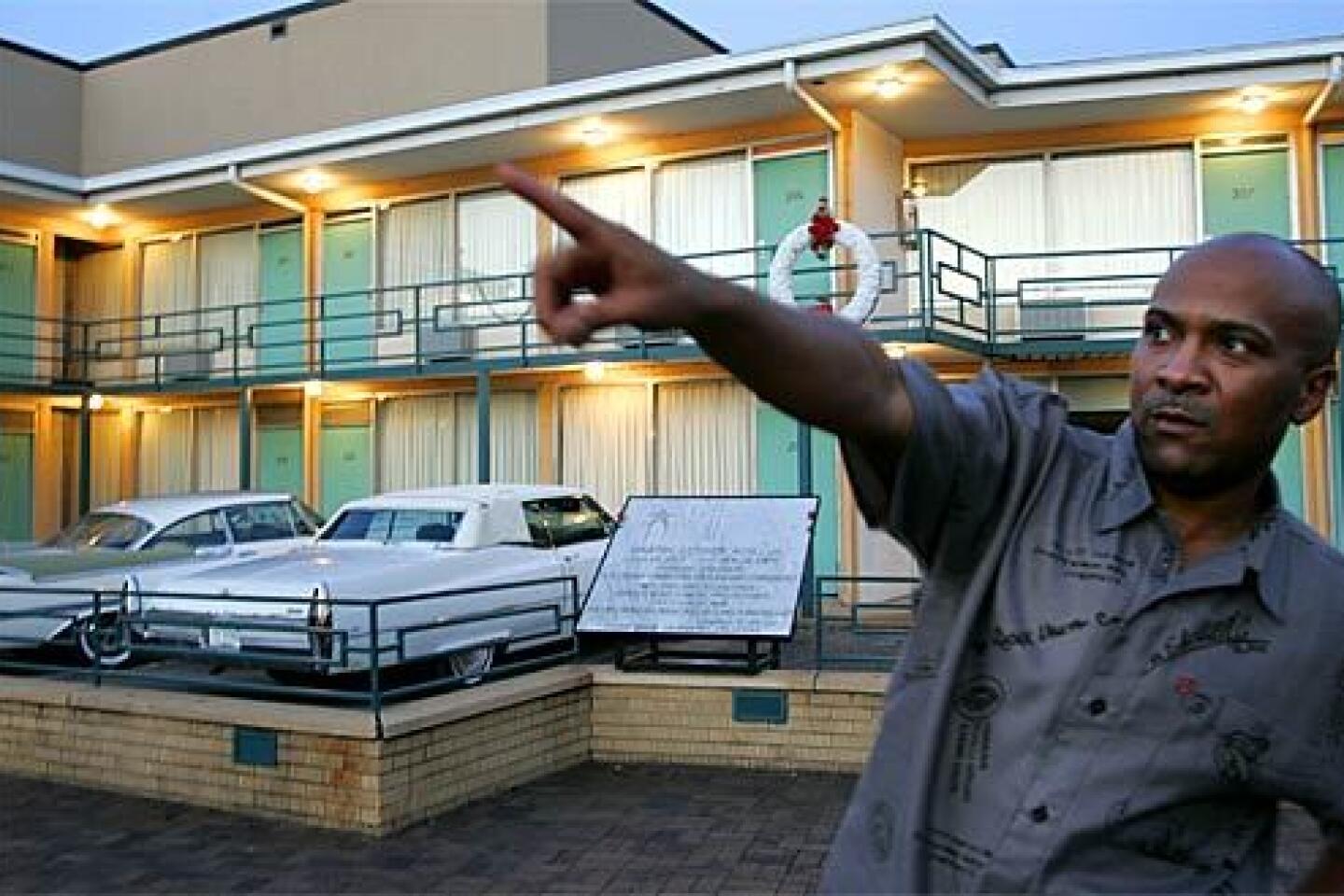

Then head a few blocks southwest to the National Civil Rights Museum, which addresses the wider story of racial struggle in this country.

The museum is at the site of the Lorraine Motel, where the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in 1968. The first thing you see when you walk up to the museum is the balcony where the shooting occurred (the motel is closed and part of the museum).

Inside, you can look through a window at the third-floor room where King spent his final hours. I’m betting it’s a scene you’ll never forget.

Authentic duck walk

For our second night in town, we stayed at the Peabody Memphis Hotel, a place with such a history that it has its own mini-museum, although the downtown hotel may be best known for its novelty “duck walks.” Twice daily, five or six ducks march through the hotel lobby as hundreds of tourists watch in amused fascination.The Peabody is just a block from the trolley line that takes you to the civil rights museum and the Arcade. It’s also across from AutoZone Park, the home of the Memphis Redbirds of the Pacific Coast League. It’s a lovely baseball park, where the opponent was the Nashville Sounds the night we were in town.

We assumed there would be a fierce rivalry between the two teams, but we couldn’t find anyone who cared that Nashville was playing — despite the potential cross-state rivalry.

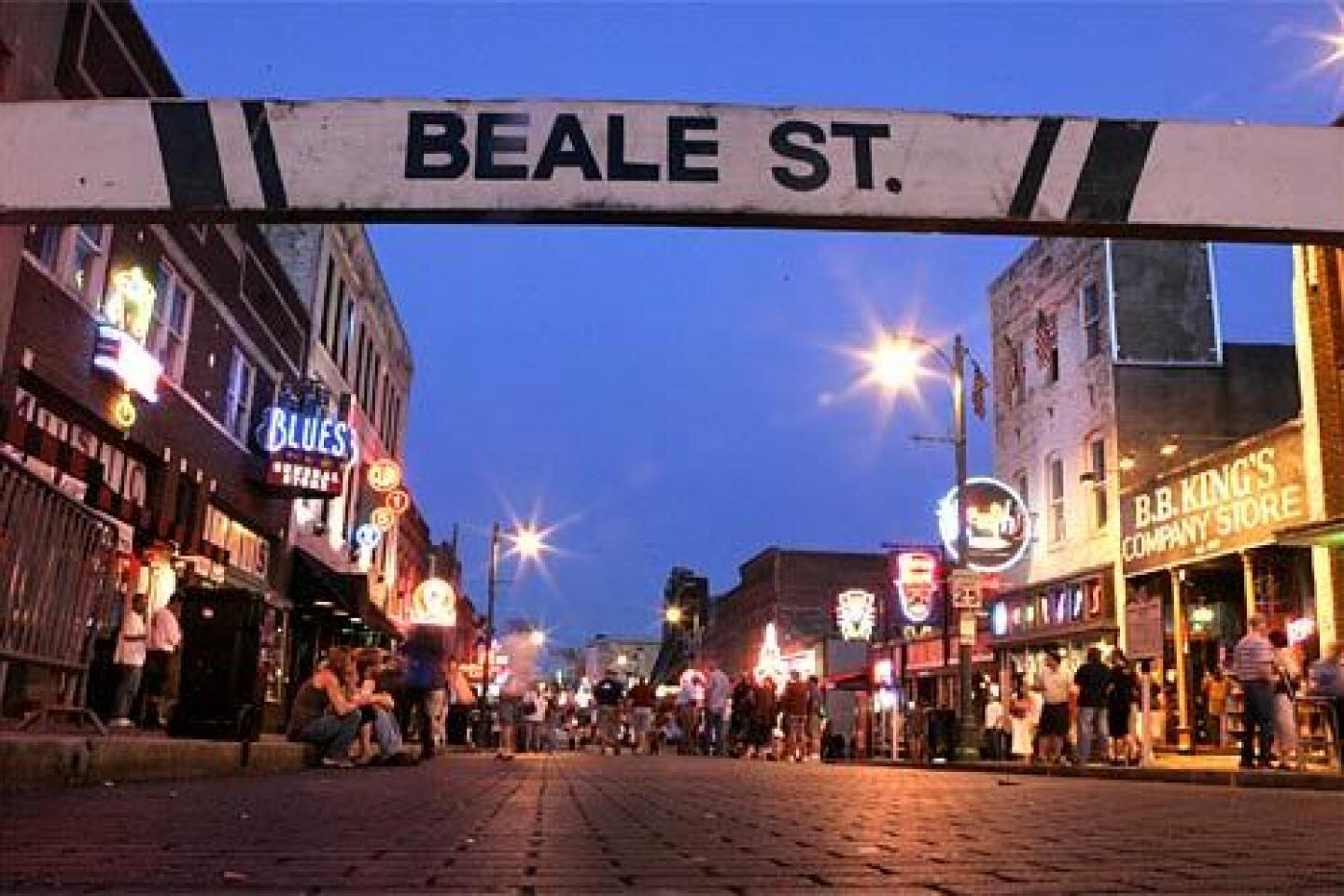

After the game, we walked to Beale Street, which once hosted one of the most active African American music scenes in the country. There are still blues and funk clubs galore, but the level of talent is pretty pedestrian.

Suddenly, Nashville was calling.

Nashville sounds

After a three-hour drive to Nashville, we were ready to start the day at the Pancake Pantry, a local favorite. But the line out front was so long that we settled for an old standby, the Waffle House, where the jukeboxes are always stocked with George Jones and Aretha Franklin.My eye caught a few songs devoted to the chain itself, so while we awaited our waffles and sugar-free syrup, I played one about working the late shift at the Waffle House. It sounded pretty good.

I was still humming the song as we headed for our primary Nashville stop — the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, which offers a superb overview of the sound that has often been called the “white man’s blues.”

The downtown location opened just six years ago and stretches for a city block without losing the down-home charm of the music.

Through the museum, you can also buy tickets for a tour of RCA Records’ old Studio B, where hundreds of recordings were made from 1957 to 1977 by Presley, Willie Nelson and Jim Reeves. It’s much larger than the Sun Studio, but there is still an intimacy.

From the Hall of Fame, it’s just a couple of blocks to the Ryman Auditorium, a place so revered as the longtime home of the Grand Ole Opry that Jack White, one of today’s hottest rock stars, got married here.

You can take a dressing-room tour, which caught me by surprise because there were no dressing rooms when the Ryman was at its peak. That’s why you’d see so many dedications to “Tootsie” on the back of country albums. The musicians often used to step across the alley between sets for drinks at Tootsies Orchid Lounge.

The dressing rooms are just an excuse for tour guides to tell Ryman stories, so the real treat is just sitting in one of the auditorium’s pews and imagining what it must have been like on some of those historic nights, such as the one in 1949 when Hank Williams did so well in his Opry debut that he sang half a dozen encores of “Lovesick Blues.”

Another downtown link with Nashville’s past is Union Station, whose massive Romanesque structure has been part of the cityscape since 1900. The old train depot is now a hotel.

When I heard a lonesome train whistle just before midnight, I figured it had to be a recording, a good-natured tip of the hat to the station’s tradition. But when I looked out my window, an actual freight train was moving on down the line.

Honky-tonkin’

After all the hours in museums, we had a craving for some live music. The most famous show in town remains the Grand Ole Opry, so we caught a Saturday-night edition at its new home in the massive Opryland resort and shopping complex about 20 minutes from downtown.It was pleasant enough watching veterans Porter Wagoner and Little Jimmy Dickens alongside current bestseller Brad Paisley, but I kept wishing it were at the Ryman, where the history of the room would have made everything feel so much more soulful.

Purists note: The Opry has returned to the Ryman for a few weeks in the winter.

Afterward, we headed back to Broadway, where the bars and honky-tonks serve as Nashville’s version of Beale Street. (Both cities are compact and easy to find your way around in.) A ‘50s-leaning country cover band named Brazilbilly was playing at Robert’s Western World, where you can buy beer or a pair of boots.

Finally, we drove across town to the Bluebird Cafe, an intimate acoustic club in a nondescript mini-mall that has been home to songwriters for nearly a quarter-century.

Although regular music fans make up most of the audience, there’s usually a sprinkling of professionals, either publishers or record execs, looking for hit material.

The Bluebird is where Garth Brooks first heard Tony Arata’s “The Dance,” which became Brooks’ signature number; a former bartender co-wrote the beautiful song “Here in the Real World,” which launched Alan Jackson’s career. Every night, the next song could be the next big country hit.

On this night, Don Schlitz — whose many compositions include “The Gambler” for Kenny Rogers and “Forever and Ever, Amen” for Randy Travis — and two of his buddies, Thom Schuyler and Fred Knobloch, sat in chairs and took turns singing new and old tunes.

As Schuyler sang, I thought about all the writers and musicians who have come to Memphis and Nashville driven by their hopes, artists as varied as Williams and Kris Kristofferson, Dolly Parton and Keith Urban. The lyrics, in part: “They walk away from everything / Just to see their dreams come true / So God bless the boys that make the noise / On 16th Avenue.”

The Bluebird was a good way to end our trip. Songwriting has always been the heart of great music, and the room’s informal setting brings you breathlessly close to the center of that creative experience. It is such a great club that don’t you just know: Someday, it too might become a museum.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.