Book Review : Real Grit of Third-World Politics

All the Wrong Places: Adrift in the Politics of the Pacific Rim by James Fenton (Atlantic Monthly Press/Little, Brown: $7.95, 269 pages)

The journalism of James Fenton--a British poet, foreign correspondent, and something of an intellectual freebooter--is rather like the places he writes about: hot, steamy, exotic, intense, sometimes darkly comic, often outrightly dangerous. It’s the stuff of Joseph Conrad, of Graham Greene: “Where there was not anger there was a frightening mixture of levity and menace,” Fenton writes of a political demonstration in Manila, thereby nicely describing his own book of reportage.

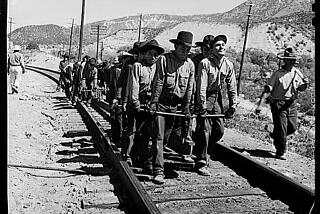

“All the Wrong Places” is an anthology of Fenton’s street-level reporting about the Third World, much of it originally written for the English magazine Granta. The American publishers of “All the Wrong Places” have chosen a trendy yuppie euphemism to describe Fenton’s turf (“ . . . the Politics of the Pacific Rim”), but the author himself announces right away that he is writing about “the Far East (as it used to be called)”--Vietnam, Cambodia, the Philippines, and Korea--from the perspective one who is “alive, conscious and with a point of view.”

Unapologetic Socialist

Then, too, Fenton’s point of view is that of an unapologetic European socialist, the kind who insists on making careful distinctions between Stalinists and Trotskyists and Maoists. (Atlantic Monthly Press offers the book in its “Traveler” series, but the book is as much about politics--and journalism--as about travel.) As a result, “All the Wrong Places” is one contemporary memoir that does not partake of the revisionism in our recent national musings over the war in Southeast Asia--Fenton perceives the American exertions in Vietnam as a crime, and nothing more.

“I considered myself a revolutionary socialist,” he writes of himself at the time of his journey in the mid-’70s to Southeast Asia as a poet, a free-lance journalist and a witness to history. “I wanted very much to see a communist victory because. . . . I believed that the Americans had not the slightest justification for their interference in Indochina.” But Fenton is also candid about his own motives, which are more resemble the impulses of the bystander who gawks at a bloody accident: “I wanted to see a war and the fall of a city because . . . because I wanted to see what such things were like.”

The pieces about the fall of Vietnam are the heart and soul of the book, full of vivid portraiture of both the victors and the vanquished. “Saigon was an addicted city,” Fenton recalls, “and we--the foreigners--were the drug.” But he brings the same caustic intellect, the same ironic sense of history, and the same intimate portraiture to his coverage of “the Snap Revolution” that replaced Marcos with Corazon Aquino (“The Filipino struggle is the missing radical wing of American politics”), and the urban agonies of pre-Olympic Seoul: “ ‘They don’t use guns or truncheons particularly,’ said somebody’s ambassador, ‘but they do use an awful lot of tear gas.’ ”

Along the way, Fenton gives a refreshingly unsentimental glimpse of journalism in the trenches of the Third World. He trashes the corporate journalism of the weekly newsmagazines; he punctures the pretentious rivalries of the New York Times and the Washington Post; and he parodies the conventional wisdom of pack journalism: “I developed a theory of journalism on which I hoped to build a school,” he cracks. “It was to be called the Crepuscular School and the rules were simple: Believe nothing that you are told before dusk. . . . The predominant colorings of the crepuscular journalists would be melancholy and gloom. In this they would reflect more accurately the mood of the times.”

Clearly, Fenton is no blown-dry network correspondent, and his experience of war and revolution in the Third World one of squalor, terror, anxiety and chaos. And, contrary to the book’s title, Fenton demonstrates a genius--a poet’s genius as much as a journalist’s--for being in the right place at the right time.

During the fall of Saigon, for example, Fenton rode the first North Vietnamese tank onto the grounds of the presidential palace in Saigon, and later he followed a crowd of looters into the abandoned American Embassy: “Some people gave me suspicious looks, as if I might be a member of the embassy staff, so I began to do a little looting myself, in order to show that I was entering into the spirit of the thing,” Fenton writes. But he left behind a plaque that quoted Lawrence of Arabia and that nicely sums up Fenton’s own perspective as a witness to history in Saigon, Manila, Seoul:

“Better to let them do it imperfectly than to do it perfectly yourself, for it is their country, their war, and your time is short.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.