The Geographic’s Graphic World

With the final issue of its centennial year, the National Geographic decided to make history and a political statement, all at once.

The gleaming gold cover that wraps around the December issue is the first all-holographic cover of any magazine, right down to the book’s spine and the McDonald’s ad on the back. “Can Man Save This Fragile Earth?” the headline asks.

For National Geographic editor Wilbur E. Garrett, the holographic cover depicting a crystal Earth that is shattered by a bullet was more than an eye-catching graphic experiment.

“Human destruction of the real planet moves slower than a bullet, but unless we change our ways, the result will be just as shattering,” Garrett wrote in an editor’s note in the back of the magazine. In a telephone interview this week from his office in Washington, Garrett added, “All I’m trying to do is blow the whistle.”

Yes, he said, the message could be interpreted as one of gloom and doom: an Earth that, under proper light, disintegrates before a reader’s very eyes.

“It’s a very serious problem,” Garrett said. “We’re hellbent to destroy the Earth.”

To convey this dramatic scenario, Garrett detailed National Geographic staff photographer Bruce Dale, as adept with a computer as he is with a camera. The three-month project proved “terribly complicated,” Garrett said, in the end consuming 200 small glass globes while Dale struggled to shatter them holographically. The final crystal globe used in the holograph came from the Steuben factory.

“I explored and rejected various methods such as explosives, freezing and heating, and sound waves,” Dale said. He consulted glass experts around the world, and finally settled on a .177-caliber zinc pellet, fired from a competition-grade air pistol with an electronic trigger. Four timing mechanisms devised by his son Greg, an electronics engineer, controlled events and the precise sequence.

Physics dictated that the globe be dropped from the air on command rather than suspended. Geographic science wizards constructed a release mechanism to drop the glass ball, and Dale came up with a computer program to calculate such variables as the velocity of the bullet, the time of delay after impact and the diameter of the globe.

The holographic explosion of the Earth was so challenging that “we needed exposure durations measured in billionths of a second,” Dale added.

Appearing on 10.8-million copies of the magazine, the holographic cover ended up costing about $2.8 million, Garrett said. Most National Geographic covers cost “a few hundred thousand,” he said.

“It won’t pay for itself in cash,” Garrett said. “But it will pay for itself in terms of bringing attention to the subject, and hopefully to the Geographic.”

Inside the holographic cover, the magazine includes an article by Paul Ehrlich about population problems around the world. The weighty topic of environmental destruction, Garrett contends, is reflective of the Geographic Society’s commitment to exploring the planet in all its dimensions. Still, he conceded, the stereotype of photos of bare-breasted women continues to dog the magazine.

“There are a lot of cliches that are hard to kill,” he said. “We haven’t had bare-breasted women around here for a long time. We don’t have bare-breasted secretaries, either.”

Rather, Garrett said, the magazine continues in the spirit of the “original guys who set this thing up 100 years ago.” Their purpose was to establish a society “so we could know more about this world in which we live.” In those days, however, color photographs were probably unimaginable, much less a three-dimensional cover of the Earth blowing up.

Meanwhile, in the magazine’s corporate headquarters, spokesman Barbara Moffet had a warning about the bold December cover.

“Be careful,” she said. “Your fingerprints come off all over it.”

Harper’s Little Secrets

Readers in Great Britain who have longed to pore over the memoirs of former British intelligence officer Anthony Cavendish need only turn to the December issue of an American magazine, Harper’s, to satisfy their curiosity about the contents of the reminiscence, banned by the Thatcher government.

“Inside Intelligence,” Cavendish’s recollections of spy duty in Latvia and Albania, among other places, was suppressed by British authorities two years ago when Cavendish sought to publish it. Instead he had it printed privately and distributed to close friends who included members of the Parliament. A copy made its way to the Times of London, which printed excerpts. The British government retaliated by obtaining an injunction, still under appeal, against further printing.

But Harper’s publisher Rick MacArthur was unruffled by the British government’s huffing and puffing. MacArthur has announced he will use the British courts to fight any attempt to block distribution of the magazine in that country. As precedent, MacArthur cited the case of Peter Wright’s “Spycatcher,” another ex-spook’s memoir, that was banned in Britain but became a best-seller in the United States. Its success overseas forced British courts to rule that the book could be excerpted in the British press.

Only 200 copies of Harper’s are sold in all of England most months, so Cavendish fans will have to scramble.

More to Read

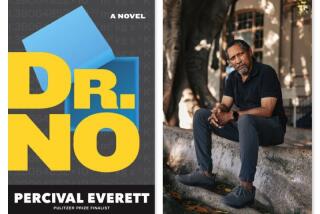

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.