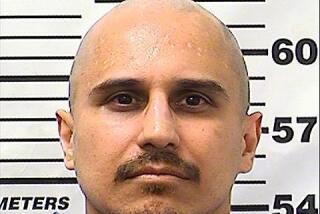

Transit Planners’ Idea Man Is on Track to Be Rail Man : Transportation: Brian Pearson is likely to take charge of designing county’s 23-mile, urban elevated line.

On weekends, Brian Pearson escapes Orange County’s infuriating traffic by bicycling with friends between Tecate and Ensenada, scuba diving or sailing his 28-foot boat, the Lone Ranger.

Come Monday mornings, however, Pearson mounts his steady steed, a Yamaha motorcycle, and heads from his Dana Point home for the car-pool lanes. And once settled in his Garden Grove office, the 14-year veteran Orange County Transit District planner helps plot the bus agency’s next moves against the Solo Commute.

“Brian,” said Santa Ana Mayor Daniel H. Young, “knows transit.”

And Monday, officials expect Pearson to be named director of a new Orange County Rail Program Office at a joint meeting of the transit district board and the Orange County Transportation Commission.

If approved, Pearson’s new job will give him a powerful role in designing a proposed $1-billion, 23-mile urban “core” elevated rail transit line through six cities--from Irvine to Fullerton--that may utilize Disneyland-style monorail vehicles.

Also, Pearson, 51, would be a key player in coordinating development of a central Orange County system with other new or expanded rail services elsewhere. These include additional commuter trains on existing tracks, the high-speed, magnetically levitated Las Vegas-to-Anaheim train, and smaller “feeder” monorail, light rail or people-mover systems planned in Anaheim, Irvine and Santa Ana.

Surrounded in his austere office at the transit district headquarters by books and artists’ renderings of transit stations, Pearson’s words cascade into a torrent of facts and visions, a reminder that he is the bus agency’s resident idea man in a hurry to get to the future.

As Pearson sees it, he’ll get there by rail.

The new job, Pearson explained, is “an opportunity to have a real impact on the development of rail programs in the county--an opportunity to be involved in the decision-making process.”

Pearson now holds the title of OCTD’s director of development, an $80,000-a-year post in which he supervised the agency’s plans for special ramps, reserved for buses and car pools, that would be elevated above congested freeway interchanges. While at the Southern California Rapid Transit District in Los Angeles in the early 1970s, Pearson planned never-built rail projects that were precursors to today’s Blue Line between Los Angeles and Long Beach, and he helped develop the El Monte Transitway, a two-way, 13-mile stretch of concrete with bus stations in the San Bernardino Freeway median.

A civil engineer with degrees and certificates in various fields from San Jose State University, Cal State Los Angeles, UCLA, Carnegie Mellon University and UC Irvine, Pearson believes that the public’s fascination with technologically sexy monorail systems is fine, but overlooks a far more important issue--choosing sites for the stations.

“Most of the focus is on the rail technology--the vehicles,” said Pearson. “But it’s the stations that must determine whether the system you build will be successful. The vehicle itself is just a box that carries people from station to station.”

The stations, he explained, must be located within high-density employment centers. And because there are no guidelines yet for cities to follow, Pearson added, it is unlikely that cities will plan office projects that will concentrate enough workers in small areas to justify locating urban rail transit stations there.

Also, Pearson said, the stations are the key to raising $500 million for the initial 23-mile core system. To make up for a funding shortfall, private firms may be sold rights to develop the stations and lease out space to retailers and other tenants.

Pearson, who helped plan the transit district’s headquarters building in Garden Grove and virtually all of the agency’s maintenance sites and suburban transit centers, acknowledged there may be citizen backlash against the high-density development needed near rail stations.

But he remains optimistic.

The airport area, the Irvine Business Complex and the South Coast Metro business district around South Coast Plaza employ 180,000 people combined, making that subregion the “third biggest downtown in Southern California,” Pearson explained. The number of workers there should climb to 280,000 by 2010, making it second only to downtown Los Angeles.

With such a concentration of jobs, the area should be able to support at least some form of light rail, he said.

Last year, however, Pearson got into a flap with McDonnell Douglas Realty Corp. over the company’s plans to build a short, $4-million monorail linking the firm’s new office complex with John Wayne Airport across the street.

In promoting the project, McDonnell Douglas officials sharply criticized OCTD for being stuck in the bus age.

At the time of flap, Pearson said that although the transit agency supports the monorail project, the monorail itself won’t provide much traffic relief. People will still motor to the airport or the office complex in order to ride it.

Pearson said this week that he will support glamorous, high-tech systems if they have a proven, commercially viable track record in a busy, urban setting. While agreeing that commuters want something “sleek,” he is unwilling to make Orange County a guinea pig.

“His no-nonsense approach is needed as a reality check,” said Santa Ana’s Young, who is himself a champion of high-tech vehicles. “He’s the glue for the whole system.”

Stanley T. Oftelie, the Orange County Transportation Commission’s executive director, said Pearson is “very thorough and thoughtful. He’s always willing to look at new technology and ideas, but he’s real conservative on ridership and revenue projections. . . . Sometimes a person’s strength is also his weakness, and that’s probably the case with Brian.”

When a new rail program office was first proposed, Oftelie, Transportation Commission Chairman Dana W. Reed and other officials agreed unanimously that Pearson should head it. He was drafted.

One reason for the unanimity, officials said, is Pearson’s ability to work with people of diverse backgrounds, including politicians and developers, knowing that some decisions must rest with elected officials.

Nor is Pearson easily turned aside.

During a fact-finding trip to Europe last March, for example, he went out on his own to examine transit and highway systems whenever government officials balked or didn’t answer his probing questions satisfactorily. He rode the Hamburg and Paris transit lines for hours on end, spanning several days, occasionally taking copious notes.

Sitting at an uncluttered desk in his office, a print of van Gogh’s “Farm House in Provence” on a shelf nearby, Pearson said the next two years will be filled with studies and proposals. He cautioned that because of the enormous lead time needed for transportation projects, the public probably won’t be able buy the first tickets on the county’s 23-mile “core” light rail system for another seven years, possibly 10. Even then, will people leave their cars at home?

“Congestion is going to increase,” Pearson said. “As it worsens and parking gets more expensive, I believe we can provide a reliable, convenient alternative to the single-occupant automobile. . . . I’m excited about the opportunity we have to give people some real choices.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.