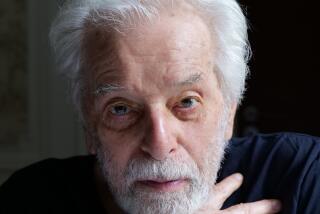

ART REVIEW : Koch Collection Out of Place : Exhibit: Yacht skipper’s art holdings make for a foul stew at the Museum of Contemporary Art that cries, ‘We want something.’

An immense, noxious yellow beast hunkers just inside the entrance of the Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego. But, if the sculpture, part of a show of work by Japanese artist Noboru Tsubaki, seems grotesque and unsettling, keep going.

Enter the second of three shows that recently opened at the museum, an exhibition from the collection of William I. Koch, skipper of America 3, and you will have reached the realm of the truly outrageous.

In the dating game that museums play to entice collectors to give art to their institutions, exhibitions of works from their personal holdings are a common and often successful lure. They are often part of a package of promises offered to the potential donor in the hope of making a lifelong match. The strategy is usually a sound one, providing the work in question is worthy of the museum’s collection.

The bulk of Koch’s art collection, alas, is not. It is a bland and at times foul stew of art assembled in the fashion of many a millionaire who wants some bang for his buck. A Florida businessman and recent champion of the America’s Cup races, Koch has gone after big names (Picasso, Monet, Renoir are represented, though not by outstanding works) and big works (Fernando Botero’s massive sculptural nudes, for instance). He has also paid excessive attention to works that relate to his own hobby, sailing.

Mediocrity appears to be the unifying theme of the collection, making most of the works unlikely museum material, and especially unlikely for a museum of contemporary art. The two dozen tedious maritime paintings here, including numerous examples by James Buttersworth, date from the late 19th and early 20th Centuries. Most of the other paintings and sculptures are equally out of place here, despite some ludicrous, superficial efforts at creating a meaningful installation.

A Mel Ramos painting of a nude pin-up girl seen through a keyhole hangs next to a Picasso nude in much the same posture, for instance, reducing both paintings to a simple comparison of naked women. And a grouping of cowboy paintings and sculpture, if not retrograde enough by itself, is paired--no doubt in the spirit of political correctness--with several objects of Indian beaded work. Surely, museum director Hugh Davies and curator Lynda Forsha, who selected the show, could not be beckoning this hodgepodge into the museum’s vault. What then, could be their rationale for such a show?

We want something from you. We expect something from you.

The message hums through the galleries with a persistent drone, like the truisms on a Jenny Holzer electronic signboard. It is a private message to Koch from the museum, but it reads like a caption to every work in this show.

Confusing the value of surface and substance has become quite a problem for the Museum of Contemporary Art lately, and this exhibition, with its attempt to cash in on the celebrity of the lender, is but the most blatant of recent examples. Deft cosmetic changes, such as renaming the museum twice in the past two years, and a recent overhaul of the institution’s graphic identity, have come at the expense of critical and art-historical contributions.

Poised on the brink of a major expansion, the museum seems, strangely, to be shrinking in ambition, scope and relevance. Economic necessity has forced cutbacks--eliminating the film curator’s position, for instance, and lengthening exhibition runs so that fewer shows are offered per year: A one-person show of British sculptor Anish Kapoor occupied the entire museum from January to July of this year. With fewer opportunities to fulfill its mandate, the museum’s remaining efforts should be of concentrated strength, not diluted fillers like the Koch collection show.

Adding insult to injury, the Koch show has been divided in half and installed in two separate galleries that straddle the installations of Noboru Tsubaki. Tsubaki’s monumental sculptures end up looking cramped in their allotted spaces, and both shows overshadow a third, Julie Bozzi’s “American Food,” which looks downright visionary in its present company.

Bozzi, who is based in Ft. Worth, Tex., has played something of the cultural anthropologist since the mid-70s, collecting and categorizing common American foods. In a 12-drawer oak chest, she presents her data: miniature recreations of entire meals, surveys of snack cakes, doughnuts, cereal, breakfast foods, carnival fare and more. Her research has clearly been extensive and the fidelity of her tiny sculptures to their models is richly varied--sometimes the likeness is exact, sometimes a coy evocation is offered instead.

The drawers, which have been mounted individually on the walls in this clean installation, are paired with drawings that act as keys to the physical evidence. Though Bozzi proposes no theories about what this accumulation of evidence might mean, the naive charm of her presentation allows us to both feel the nostalgic tug toward these familiar foods and also to look at them anew, as if relics from another civilization.

Tsubaki, a young artist from Kyoto, has far less endearing things to say about human occupation of the planet. His two large installations here signal worlds gone amok, with “Rubbing Band” a metaphor, perhaps, of the industrial world that functions smoothly, continuously, but accomplishes nothing.

“Rubbing Band” consists of a huge egg-like sphere, seemingly of fiberglass and lit from within, which turns slowly in a tangerine-colored gallery. A clumsy arm sprouts from one side and drops down into an accompanying bucket filled with a shallow layer of orange marmalade. As the sphere turns, the arm drags the bucket along, and the vessel’s wheels etch their circular course into the gallery floor--rubbing a band, as the title suggests. It’s quite a small pun, however, for such a mighty contraption.

“Fresh Gasoline” is the title of the 10-foot-high acrid yellow blob that greets visitors at the entrance to the museum. It harks from the natural world, albeit one that has suffered at the hands of genetic engineers and a poisoning population of ordinary citizens. Organic and orgiastic, its scaly, barnacled skin seems to be expanding, folding in on itself, then oozing forward, unleashed. A host of spiny fingers stretches upward from its back, like a sea urchin’s protective spikes.

Tsubaki’s work is an exercise in approaching the ungainly, the unsightly, and recognizing it as one’s own. As such, it is good preparation for the further offenses within.

* Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego, 700 Prospect St., La Jolla, through Sept. 26. Open Tuesday through Sunday 10-5, Wednesday evenings until 9.

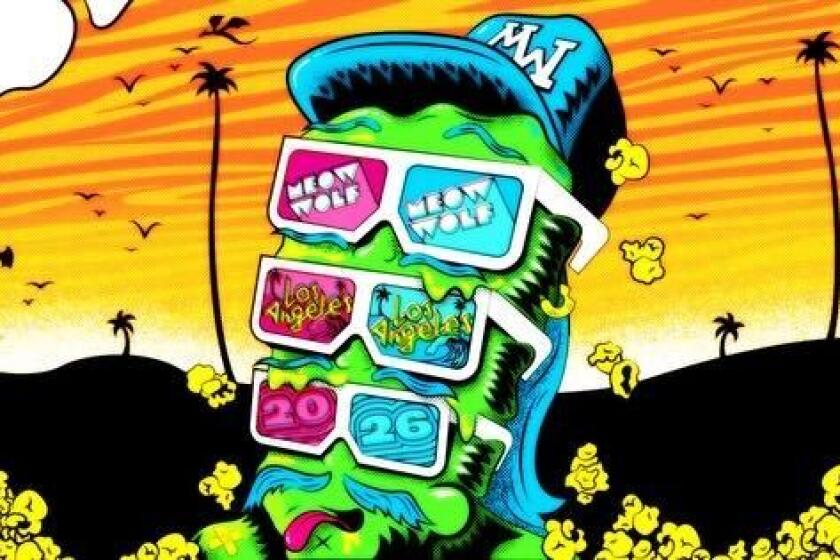

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.