Sterile Medfly: Giving Eradication Plans Bite : Infestation: Insects are zapped, chilled and set free, so that fertile counterparts will vainly mate with them.

On their way to becoming the state’s chief weapon against Mediterranean fruit fly infestations, a couple of million members of the breed are dyed pink, bathed in radiation, chilled and then dropped 1,000 feet from an airplane.

Then, these sterile flies are supposed to wipe out future generations by mating with their fertile counterparts.

Nobody said love was easy, but the complicated sterilization process that takes the Medflies from a lab in Hawaii to a laboratory at the Armed Forces Reserve Center here makes the average courtship seem simple.

More than 610 million neutered flies are being cranked out each week to fight three separate infestations in the Southland, including one in Westminster where state workers are dumping 26 million Medflies weekly by air and land.

“We’ve made a longstanding commitment not to let this insect get a foothold in the United States,” said Gary Agosta, who supervises the state laboratory at Los Alamitos. The sterile-release program, run from the laboratory at the base, is the largest of its kind in the Western Hemisphere. And despite some research that calls into question its effectiveness, the program is the cornerstone of the state and federal governments’ plan to eradicate the fruit-destroying pest.

The idea is simple: neuter millions of Medflies, then dump them in the wild to mate with their feral counterparts. The flies become their own destroyers, disrupting the species’ chances at reproduction.

The reality, though, is a small miracle of biology.

To lessen the chance of an accidental escape of wild flies here, the Medflies are reared in Hawaii, where the pest is already established. There, the eggs are raised to the pupae stage, when the maggots form a hard casing around themselves before developing into adults.

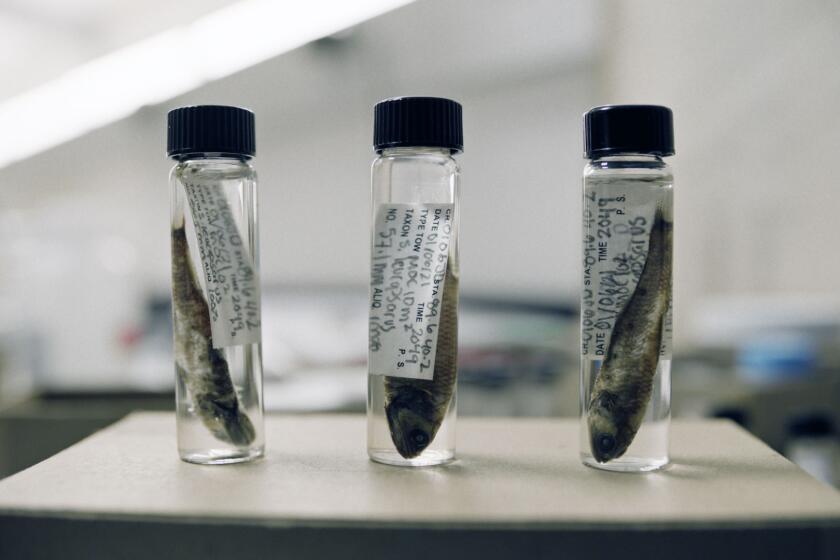

State and federal workers collect the pupae, coat them with fluorescent pink dye, and stuff them by the thousands into “sausage bags,” so-called because of their shape. The bags are next put through a low-level radiation bath, neutering the bugs inside, and then shipped to the Mainland.

“At that point, it’s almost like they’re in a state of suspended animation,” said Larry Hawkins, a spokesman for the state Department of Food and Agriculture.

Once here, the already sterilized insects hatch, marking themselves with the pink dye as they push their way out of their casings. The dye provides a way of telling the barren flies from the wild ones when state workers check the traps that monitor the infestations.

The full-grown flies are then put into a dark room for a couple of days--a practice that makes them, well, sort of lusty.

“We keep the lights out. We want them to be ready to go,” said Stuart Stein, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s lab director in Los Alamitos.

To prove his point, he guides a visitor into a darkened trailer filled ceiling to floor with boxes of sterilized flies--19.5 million in all. Stein flips the light switch and, as if on cue, a furious humming fills the room.

“See?” he says. “We want to save all that energy for when they go out in the field.”

But even a dark room can’t keep a good fly down. As Stein walks from one trailer to another, sterilized Medflies occasionally fly by, sticking to his skin and glasses. “With this many flies, it’s hard not to have any get away from you,” he says.

So to minimize the flight risk, the Medflies are cooled to 38 degrees before being released from airplanes. As they are dropped from an altitude of about 1,000 feet, the flies warm up. They instinctively head for the fruit trees where they make their homes--and, state workers hope, find their mates.

The flies are not dangerous to humans, nor are they likely to be seen. They stick to the orchards and gardens that contain the more than 250 kinds of fruits and vegetables in which they can lay their eggs.

Controlling the fly is a high priority both to protect back-yard fruit and to keep the infestations from spreading to the state’s agricultural heartland.

That’s what makes local outbreaks dangerous to the state’s multibillion-dollar agriculture industry. And it’s also why state workers say they can’t give up on efforts to eradicate the pest.

“The economic consequences would be pretty dramatic for everybody,” said Hawkins. “And besides that, how many Southern Californians who brag about the fresh fruit in their yards are going to tolerate maggots in their fruit? Not a lot.”

The state’s confidence in the program’s efficacy flies in the face of some recent research that says efforts to halt the flies are too late. Not only is the insect a California resident, these researchers say, but the current method of releasing sterile Medflies also is doomed.

The reason: The barren Romeos just don’t have the right breeding stuff, and wild flies are more attracted to their wild brethren than to their nerdy, lab-raised cousins.

To counteract that problem, said Ken Kaneshiro, a University of Hawaii entomologist who has studied the bug, the program must be carried out for a longer period of time. Currently, an area is usually blanketed with sterile flies for nine to 10 months, which covers four generations of the Medfly.

“We should go at least for six generations, if not longer than that,” Kaneshiro said. His study found that even when sterile Medflies outnumber feral ones by more than 60 to one, mating between the two groups occurs only about 37% of the time.

The lab-raised flies seem unable to effectively perform the elaborate courtship rituals needed to attract the picky wild flies, he said.

State officials, though, discount Kaneshiro’s study, saying more research needs to be done. And since infestations have been successfully eradicated, they say, the effectiveness of the technique speaks for itself.

“This is a proven program,” said Agosta, pointing to the eradication of the pest around Whittier during the 1989-1990 infestation. No flies have been found in that region in three years.

Barren Flies Orange County receives about 34 million sterile Mediterranean fruit flies a week through a state program to eradicate the pests locally. They come from a laboratory in Hawaii that produces 610 million flies a week for various programs throughout California. 1. In mating cages containing about 2 million flies, females deposit eggs onto a sweet, jellylike substance. Eggs are incubated at 80 degrees for three days. 2. Larvae hatch, are collected into large bins, mixed with vermiculite food and stored at 70 degrees. 3. In two days larvae develop into pupae. They are sifted from the vermiculite and placed on screened trays, where they mature for about 10 days. During this period they are dyed pink for identification purposes. 4. Sausage-shaped bags are filled with pupae and irradiated with cesium-137 for three minutes, completing the sterilization process. 4. Pupae are collected into bags and irradiated for three minutes. 5. Bags are packed into boxes, refrigerated and shipped. Within a few days, pupae mature into flies and are released into infested areas. Source: California Department of Agriculture; Researched by APRIL JACKSON/Los Angeles Times

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.