Disaster Victims Must Be Wary of Con Artists : Americans Continue to Ignore Warnings of Fraud

Perhaps an investigator in the consumer protection unit of the San Francisco district attorney’s office said it best. Months after the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake had devastated the Bay region, a small army of people intent on committing frauds had surfaced to prey upon an oddly unsuspecting populace. As Laurel Pallock put it then, “we’re trying to warn people that the con artists are coming out of whatever woodwork you have left.”

We Americans apparently have a very short attention span for this sort of thing, but this is a matter that ought to be permanently etched in our memory. After all, we have hardly seen the last mudslides, wildfires and earthquakes, right?

Well, let’s get it straight, shall we? Whenever a disaster of national significance occurs, a certain earthbound breed of vulture will be sure to follow closely on its heels. The bigger the pot--in terms of massive federal relief--the more numerous the shysters, schemers and scoundrels.

Why is this so hard to remember?

Sure, there have been inventive tragedies of opportunism in every such disaster, such as the Bay Area “home invaders.” As one such “contractor” assessed damage at a victim’s home, for example, the other riffled drawers and stole whatever valuables could be quickly pocketed.

But there is a depressing similarity to much of the fraud that occurs. It is a litany that makes it difficult to believe that disaster victims can continue to fall prey to the same old schemes. Examples abound.

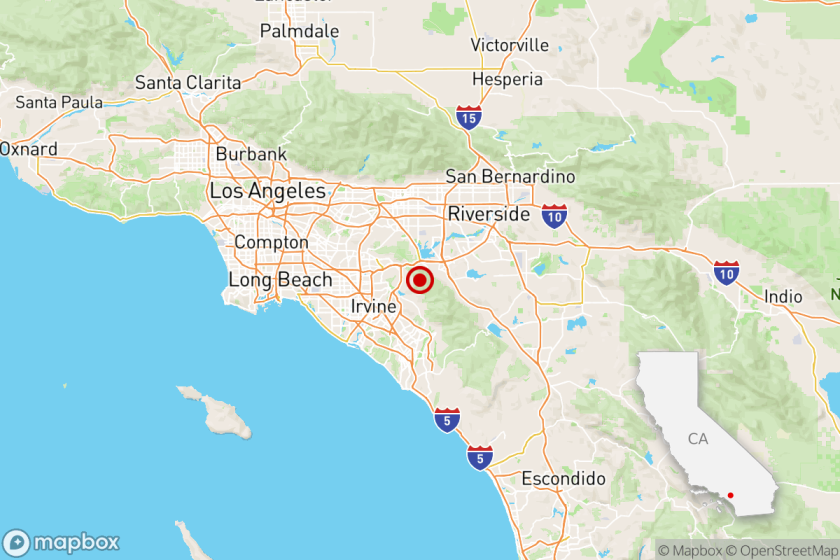

In Los Angeles, in 1987, after the Whittier earthquake, there were countless stories of contractors who demanded payment in advance, started work, and never finished it. There were unlicensed contractors who were never checked out by customers and who turned in shoddy work.

In Santa Cruz, after Loma Prieta, some opportunists charged $100 just to show up for a damage estimate and added fees amounting to $50 an hour for the time spent making the estimate. Even though that was a clear violation of California’s fair-business practices, and should have seemed odd in the first place, gullible homeowners paid such outrageous charges again and again.

In Richmond Heights, Fla., in the aftermath of Hurricane Andrew, there were the Dorothy Franklins and Alex Allens and the Mary Margolises. Franklin shelled out $20,000 to a contractor who did not have a license in the state of Florida. The work the contractor did do (which wasn’t much), had to be ripped out and repaired. Allen gave a roofer $7,300 up front in Federal Emergency Management Agency funds, and never saw the roofer again. Margolis gave $40,000 to a work crew to have them fix her home; they disappeared.

It should therefore come as no surprise that exactly the same type of parasite has surfaced here, hoping to feed at the trough of the largest federal aid package ever amassed for a natural disaster.

To avoid such types, the following rules should apply:

* Make certain the contractors have cards issued by the Contractors State License Board. Then call the board (1-800-321-CSLB) to make sure the contractors’ numbers are valid and to see whether there are any actions pending against them.

* Obtain several estimates.

* Refuse to be pressured into a hasty decision. The more a would-be contractor tries to hurry you, the more suspicious you should become.

* Be wary of overly generous discounts. They are as much of a warning signal as cost estimates that seem outrageously high.

* Slam the door on those who tell you that city building permits are not required for major repairs.

* Show the door to anyone who demands advance payments of more than $1,000 or more than 10% of the total bill. The federal government’s generosity, to date, should not be squandered on the parasites.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.