O.C. Art : A Question of Stature : Did Childhood Polio Give Dorothea Lange a Special Affinity With Her Subjects?

Public attitudes toward disability have changed radically since the 1930s. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who had polio, took great pains to project an able-bodied image during a period when the entire nation suffered from the economic ill health of the Great Depression. Today, controversy surrounds a planned Washington, D.C., memorial to Roosevelt because none of the sculpted imagery will show him in a wheelchair or using a cane.

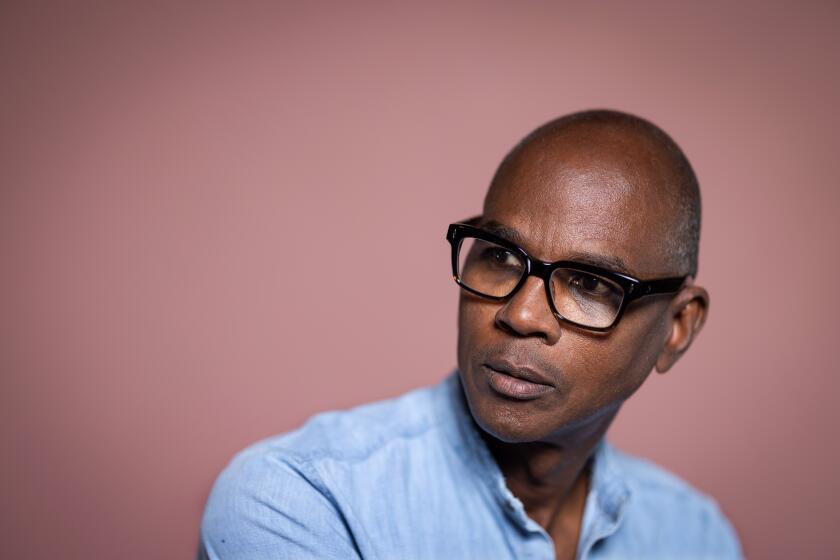

But disability appears to have had a different impact on another famous New Deal image-maker, photographer Dorothea Lange. An essay by Sally Stein, an associate professor of art history at UC Irvine, proposes a link between Lange’s childhood bout with polio and her unusual empathy with poor and displaced men and women of the Dust Bowl and the Deep South.

In “Peculiar Grace: Dorothea Lange and the Testimony of the Body,” Stein discusses how Lange used images of physical exhaustion and discomfort, rather than facial expression, “to view the trials of the Great Depression as something registered and grappled with first and foremost in the body.”

Singled out for praise in the New York Times Book Review last month, the essay was published recently as one of seven in “Dorothea Lange: A Visual Life,” edited by Elizabeth Partridge (Smithsonian Institution Press; cloth, $55; paper, $24.95).

Stein writes that Lange, who had a pronounced limp, had been schooled by her conventional-minded mother to “walk as well as you can” when out in public. When the teen-age girl first witnessed the “peculiar grace” (as she later put it) of plump, aging modern dancer Isadora Duncan, she was captivated by--in Stein’s words--”a model of artistic authority that celebrated the body’s idiosyncratic capacity for expression.”

*

Beginning in early 1935, Lange and Paul Taylor, an economist specializing in migrant labor issues whom she married later that year, began documenting the rural homeless for the Federal Emergency Relief Administration. During the remainder of the decade, Lange mostly photographed for the Farm Security Assn., founded by Roosevelt to deal with the problems of poor farmers.

People in Lange’s photographs--migrant workers, a man in a bread line--are often seen squatting, sitting with legs sprawled or leaning on a wall or fence. This leaning posture, Stein writes, suggests that “the inability to support oneself economically has as its corollary an inability to remain physically erect.”

Stein speculated in a recent conversation at a restaurant near campus that Lange’s limp may have been “a way of creating common ground (with her sitters), a visible sign of comparable distress, (as if to say,) ‘I’ve known suffering, too.’ (Illness) had taught her something about being outside (the mainstream), which is a good lesson for someone who wants to make serious and distinctive imagery.”

In many of Lange’s images, “everyone suddenly develops a kind of physical impairment, as if to create a community of distress and disability,” Stein said, adding that such depictions give everyone an almost mythic aura while denying “the specific implications of what it means to be physically disabled, as opposed to socially--in terms of class and money.”

In New Deal cartoons of the ‘30s, a cane or crutch indirectly referred to the President’s condition as well as to economic and social reforms. Stein said she is interested both in such public treatment of the disability issue and the way Lange personalizes it, making it “much more visceral and real.”

A photography historian whose melodious voice and direct gaze readily convey her keen engagement with ideas, Stein is particular interested in the pre-TV era. During the 1920s and ‘30s, she said, the growth of consumer culture competed with widespread nostalgia for the 19th-Century ideals of a close-knit community, creating “a moment of ambivalence: a country and a culture standing at the crossroads.”

*

Initially, Stein had thought there was little to add to the extensive literature on Lange. But writing about Lange and the body sparked several new areas of inquiry. She is planning to publish a monograph on Lange that also will include essays on the influence of widely disseminated reproductions of 19th-Century paintings (particularly Jean Francois Millet’s “The Gleaners”) and the unconventional way the photographer depicts gender roles.

Stein believes that Lange “restaged” the Jean Francois Millet’s famous painting, “The Gleaners,” for her “Filipino Lettuce Pickers” photo from the mid-1930s, substituting a boy throwing grasshopper bait onto the fields--”a very good translation, given the fear of pestilence and the various scourges of the ‘30s”--for the boy sowing seeds in the painting.

Although Lange was never quoted about works of art that influenced her, she clearly was trying to make artistic images, and her first husband, Maynard Dixon, was a painter.

But how would she have known about Millet?

“When we think of popular culture today, we think of cartoons and TV and ‘Beavis and Butt-head,’ ” Stein said. “We don’t think of paintings as part of . . . everyone’s field of daily reference and imagery.”

In Lange’s day, however, virtually everyone was familiar with a painting like “The Gleaners.” It was one of many sentimental works reproduced in cheap art lithographs that were meant to grace the humble living room as well as the schoolroom and library.

*

Lange’s documentary approach, Stein said, “was quite radical in some ways, (showing) how the poorest lived, warts and all. . . . By using Millet, she is making her imagery more acceptable and resonant to people who unconsciously may be reminded of images they’ve grown up with.”

But doesn’t this idea of “restaging” somehow contradict our notion of documentary photography as being absolutely true to fact?

“It is one of the great myths of documentary,” Stein replied, “that documentarians never ask people to pose. . . . In (Lange’s most famous image,) ‘Migrant Mother,’ if you look at the entire (sequence of negatives), it starts with a much more jumbled image--with a teen-age girl, for example, who doesn’t appear in the final group.”

That first shot showed a woman “who’s full of despair and in a completely disorganized setting, giving a sense of social disorder as well,” Stein said, “raising concerns about whether we want to support families that are producing loads of children that may become, in a sense, wards of the state--a very familiar issue to us right now.”

By moving the camera into a vertical position and subtracting several of the women’s children, Lange made the group appear “like a good nuclear family with 2.2 children rather than four or five, to give a sense of family coherence (despite) the absent father.”

*

Stein said her third essay will be about the way Lange’s images most often show “not family cohesion but family tension. In this perspective, ‘Migrant Mother’ is a very anomalous image in her work, and even it (conveys) a sense of claustrophobic tension, and the absence of a father.

“I’ve been struck by the number of images where there seemed to be an emphasis on a solitary uncomfortable, or even deformed, body, which I think is often a projection of her own preoccupations,” she said. “And there are images of families that seem to be splitting apart. . . .

“Her formative experience as the child of a disintegrated family (her father decamped when she was 12) left her profoundly scarred and in search of more cohesive family units,” Stein said.

“This gets into a primary issue in photography: How much is projection? Not only what we as viewers read into images, but what photographers are ‘reading’ in the world in terms of what they go looking for. . . .

“I think there are lots of ways to overturn some of what has become conventional thinking about documentary (photography) in general and Lange in particular,” Stein said. “What I want to avoid is doing biography as a substitute for art history. I want to look closely at images and figure out how to weave them together so that there is some interesting, but never perfectly fitting, relationship between life and work.”

More to Read

More to Read

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.