Graffiti Paints Picture for Police

Dan Jaramillo, a Los Angeles Police Department gang detective in the Hollenbeck Division, looked for the usual spent casings and bullet holes when he received a call in October to investigate the shooting of a 10-year-old girl and a 19-year-old man.

It was clear from the start that it was a gang hit. But which gang? Hollenbeck police say there are 37 in the East Los Angeles area.

As it turned out, the killers might as well have left a signed confession. Graffiti on a concrete wall read like a street hieroglyphic. The tragedy had started with the male victim’s gang tagging in the suspect gang’s territory. Detectives confirmed the rivals’ names, written out in bright spray paint.

Law enforcement officers know that to gangbangers, walls are like newspapers and detectives read them very closely. But a renewed effort by activists and the City Council to clean up graffiti--launched in the wake of a new report showing Los Angeles graffiti rising 24% from October 1999 to October 2000--will ironically affect an important tool used to decipher gang activity, law enforcement officials said.

Los Angeles City Council members proposed in January to increase the budget for graffiti removal by $3.1 million to $5.8 million and step up coordination with state and county agencies to combat the spray-painted messages and drawings.

Cleanup crews said the writing is getting more violent, and that they are being threatened by gangsters who do not want their work erased.

“I’m comfortable in knowing they’ll never remove all the graffiti,” said Dave Demerjian, former chief of the hard-core gang unit for the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office. “We would lose valuable evidence if all walls were wiped out.”

Of the hundreds of gang-related cases Demerjian has prosecuted, graffiti has helped as corroborative evidence in about half, he said. In gang-related trials, he said, officers and detectives often will bring in photographs of area graffiti relating to the alleged crime, and a gang expert will interpret the drawing for the jury and judge.

Sometimes, graffiti reveals which gangbangers hang out together and helps detectives and prosecutors determine who may have been involved in a crime, Demerjian said.

Graffiti also can illustrate the progression of gang warfare, said Tony Moreno, supervisory detective for the LAPD’s career criminal gang section.

“They’ll write the name in. The next day it’s crossed out. The next day, a reply . . .,” Moreno said. “It’s a way to get a feeling for the various politics.”

Traditionally, gangs mark walls in their territory with their gang name, detectives said. Symbols can be as simple as words or as sophisticated as penal codes--such as 187 for murder when written by a rival’s name. Crossing out a name is considered disrespectful and grounds for retaliatory drive-bys or outright gang wars. Telephone area codes and letters of the alphabet indicate regions. For example, 14, which represents the letter “N” in the alphabet, refers to Northern California gangs.

“Graffiti was a way of saying ‘This is us,’ ” said former gangbanger Robert Olvera, 30, who supervises a graffiti cleanup crew in Boyle Heights. “It was a way to hold your own.”

Latino and African American gangs typically tag their home territories more often than Asian and white supremacist gangs, authorities said.

Steven L. Gomez, FBI supervisory special agent, said gangs differ in culture throughout the U.S. from biker gangs to Latino crews to white prison clans, depending on the region. He said some areas, like New Orleans and Miami, have “street crews” instead of gangs though there is little difference in the groups’ criminal activity.

He said nationwide and in Los Angeles--considered by law enforcement to be the hub of gang activity--most detectives use graffiti for clues.

The LAPD’s Jaramillo said that when detectives in his unit learn a wall might be painted over, they rush out to photograph it for future reference.

With an increase in tagging, he said, comes an increase in burglaries, robberies and shootings.

“When one gang crosses out another a lot,” Jaramillo said, “you know something is coming. You tell officers. You try to direct additional units [to the area].”

But not everyone agrees.

Carlos Sanchez, gang detective for the LAPD’s Foothill Division, which has more than 30 gangs of all ethnicities, said graffiti provides a clue. “We look at it, but it doesn’t necessarily help us solve crime,” he said.

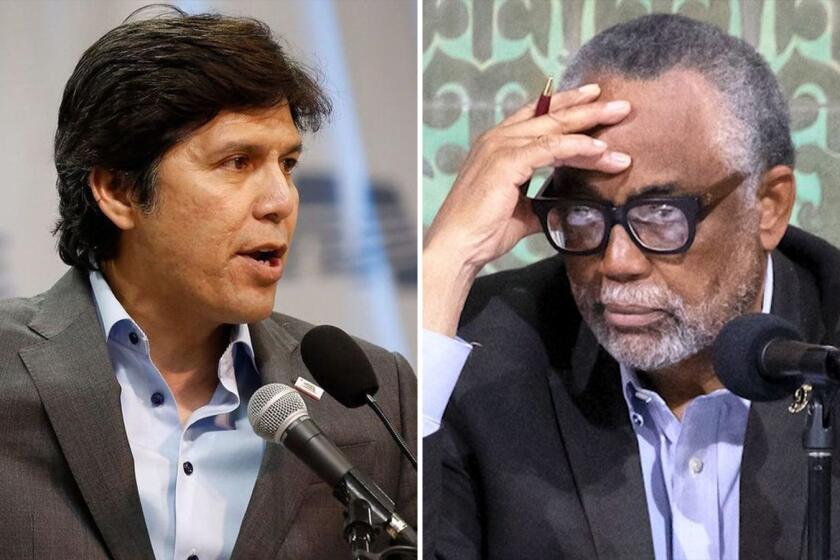

Malcolm Klein, a professor emeritus of sociology at USC who has researched gangs for four decades, said that in all the gang-related trials in which he has testified, graffiti has never served as a major clue. Graffiti-writing is simply about attracting attention, he said.

“Who’s putting his name up doesn’t tell you anything about the guys that aren’t,” Klein said.

Olvera and his crew of five have begun to pay back what some of them call a debt for an adolescence of graffiti-writing. Removing graffiti with violent cross-outs is their first priority because they want to prevent future wars, he said.

“I was active doing everything you see here,” Olvera said. “Now I feel sorry for everything that I did.”

*

Times staff writer Noaki Schwartz contributed to this story.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.