It’s a battle of wills in a silent reality

RACHEL is a genius. She has a MacArthur grant to prove it. She also lost her son at the supermarket -- his abduction and murder shattering her belief in the ability of the mind and her chosen field, linguistics, to control the world around her. She seeks to regain that control by attempting the impossible: teaching language to a mute young man accused of killing the father who chained him in the basement for most of his life.

Then Susan barges in. The psychology grad student claims that she was sent to evaluate Rachel’s patient -- whom she calls Cal, as in Shakespeare’s Caliban -- and will take custody of him after his lessons fail. Which they will, she says, because what Cal needs is nurturing, not the flashcards Rachel insists on flipping at him.

The women’s battle of wills forms the heart of Stephen Sachs’ “Open Window,” a co-production between the Pasadena Playhouse and Deaf West Theatre, which commissioned the play because -- oh, yes -- did anyone mention that Rachel, Susan and Cal can’t hear? Their condition is a fact of life, but not the fact in their lives. Each has bigger dilemmas to confront.

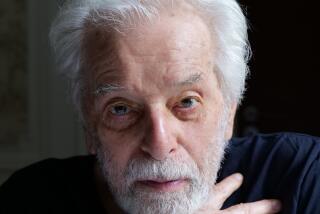

Sachs says he and Deaf West artistic director Ed Waterstreet wanted to tell a story not about deafness but about people who happen to be deaf. When they started discussing ideas five years ago, they were intrigued by reports about a so-called wild child.

Their attention soon shifted to the adults who helped such children reenter society. “We wanted to look at intelligent, articulate professionals,” says Sachs, managing artistic director of the Fountain Theatre. “ ‘Open Window’ is really about the struggle between the two women.”

It also is about what language can and cannot do. “Cal and Rachel are at opposite ends of the spectrum,” Sachs says. “Rachel is a nationally renowned linguist. Then there is this thing, this man who is language-less. But both of them are crippled souls who share isolation. Susan believes Cal doesn’t need language so much as human contact. Maybe she also is trying to get Rachel to remember that what language does, besides create logic and thought, is to enable us to connect to another human being.”

The production may remind audiences of both the power and frailty of such connections. “Open Window” is being presented in Deaf West’s signature blending of spoken English and American Sign Language. Nonhearing actors, who are playing the central characters, sign while their lines are being voiced by hearing actors who represent a Greek chorus of sorts.

“As I wrote I thought about how the play would work in the air as opposed to the ear,” says Sachs, who can hear but is fluent in ASL. He is curious to see how deaf audiences will react to the script’s emphasis on language and literary references, including the many like Caliban -- a monster who learns to speak -- that come from “The Tempest.”

He hopes those who can hear will understand that just because others can’t, that doesn’t mean they also can’t think or feel or that they can’t be a mother, an overachiever or, in Susan’s case, an ambitious protegee. In other words, says Sachs, here are characters you don’t see onstage: “Deaf people, for starters, but also deaf people who are not saints.”

An approach born of frustration

“OPEN WINDOW” is the next step in the 62-year-old Waterstreet’s quest to create a new kind of theater, one in which the deaf and the hearing enjoy a shared, if not identical, experience. After college, he spent years in traditional theater-for-the-deaf, which left him frustrated at the way playgoers were forced to rely on supertitles or signers on the side of the stage.

After Waterstreet and his wife, actress Linda Bove, came to Los Angeles in the 1980s, he started his own theater. In 1990, he met Sachs, who had opened the Fountain in Hollywood with choreographer Deborah Lawlor. Sachs, 46, became interested in deaf culture in 1987 when he watched an ASL interpretation of one of his plays. The Fountain gave Deaf West its first home and hosted programs for deaf writers and poets. In 1997 it presented Sachs’ “Sweet Nothing in My Ear,” about the conflicts between a deaf mother and a hearing father whose son is eligible for a cochlear implant.

In the mid-’90s, Deaf West moved to North Hollywood, where it won acclaim for dramas like “A Streetcar Named Desire.” Then Waterstreet fulfilled a childhood desire to “do something crazy -- a musical for the deaf.”

He and managing director Bill O’Brien recruited Broadway veteran Jeff Calhoun to direct a hit revival of “Oliver!” A couple of years later, their imaginative reinvention of Roger Miller and William Hauptman’s “Big River: The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” played to sellout crowds before transferring to the Mark Taper Forum. In 2003, the show went to Broadway, where a Roundabout Theatre Company co-production earned special Tony honors. National tours visited 39 cities in 49 weeks.

Waterstreet and O’Brien give credit to Pasadena Playhouse artistic director Sheldon Epps for committing to Deaf West before “Big River” made it big. “This was a real leap of faith on his part,” O’Brien says.

“It was a leap,” says Epps, “but anything in the theater is a leap. Shakespeare. Moliere. Tom Stoppard. You never know.”

Epps discovered the art of signing years ago during a visit to the National Theatre of the Deaf in Connecticut. Shortly after he joined the playhouse in 1997 he saw “Oliver!” and began talks with Waterstreet and O’Brien that led to “Open Window.”

For the director of the Pasadena production Epps suggested the Steppenwolf Theatre Company’s Eric Simonson because he had seen his staging of “The Song of Jacob Zulu” with the South African singing group Ladysmith Black Mambazo.

“I was impressed with his ability to synthesize the visual, the language and the music in a theatrical way,” Epps says, “and how he worked with a culture that was not his culture, just as deaf culture is not his culture.”

In “Open Window,” Simonson says, he was struck by the way “the completely visceral quality of a signed performance automatically heightened the process” and encouraged the use of effects -- video, evocative music, rain -- that would have seemed “out of place and distracting if the actors were merely speaking their lines.”

“I’m not sure we planned any of that from the start,” he says. “It just sort of naturally evolved in the presence of the deaf artists. That was amazing.”

The show’s three main actors have Deaf West connections. Rachel is played by Bove, a distinguished stage performer. Shoshannah Stern, a graduate of Deaf West’s summer program, is Susan. Chris Corrigan, who plays Cal, starred as Huck in the Washington, D.C., production of “Big River.”

Epps says “Open Window” fulfills his desire to promote diversity -- which he says people think is just about color. “It’s also important that we deliver many styles of theater,” he says. “When I started here subscribers would say they had trouble putting a finger on what I did. Now they look forward to the idea that they don’t know what to expect.”

Epps also has been cultivating local collaborations. Next year he and Cornerstone Theatre Company will present a Pasadena-centric version of Shakespeare’s “As You Like It,” adapted by Cornerstone co-founder Alison Carey. The Furious Theater Company has taken up residence in the playhouse’s small upstairs space.

“A lot of people want to position ‘Open Window’ as some sort of strange or different experience,” Epps says. “It’s not. This is what we do here.”

‘Another reality’

AS does “The Tempest,” “Open Window” begins with a storm. Flashes of light slice through the darkness. Thunder roars. The weather’s ferocity flows through Rachel’s and Susan’s faces and hands. One challenge, in fact, is getting the chorus’ spoken words to match the eloquence of the physical acting. “The hearing and nonhearing actors have to sync up emotionally,” Epps says. “Two people must become one.”

The exception is Cal, who cannot speak or sign and so has no one translating for him. While he is always onstage he, in many ways, is always alone. “Cal’s in another reality,” says Sachs, “one that verges on the magical.”

In one of the most affecting scenes, that magic finally touches Rachel, who begins to wonder if this flailing man-child knows about her lost son. She relives that last trip to the market -- when she looks away for a minute, then realizes her boy is gone. For the first time in Rachel’s life, words fail her. For the only time in the play Bove tries to talk, the choked noises she makes are a jarring contrast to her commanding presence and the smooth tones of the actress who voices for her.

As the audience thinks twice about its reactions to Rachel/Bove, the chorus notes that no one in the store can understand the mother’s cries for help until it is was too late.

Such moments verge on the communal theater experience Waterstreet dreams of. He knows, however, that truly uniting the cultures will take much more work. Even so, he says, “ ‘Open Window’ is a great opportunity, a coming together of deaf and mainstream, Pasadena and us, Stephen and me.” He smiles. “Plays like this help me learn a lot about what it’s like to be a hearing person. That’s what’s cool about these collaborations.”

*

‘Open Window’

Where: Pasadena Playhouse, 39 S. El Molino Ave., Pasadena

When: 8 p.m. Tuesdays to Fridays,

5 and 9 p.m. Saturdays, 2 and 7 p.m. Sundays. Call for exceptions.

Ends: Nov. 20

Price: $37-$53

Contact: (626) 356-PLAY

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.