U.S. to press Musharraf to compromise

Fearing the collapse of a friendly government, the Bush administration has begun a concerted public effort to salvage the embattled presidency of Pakistan’s Gen. Pervez Musharraf by pushing him to compromise with political opponents and abandon emergency rule, U.S. officials said Thursday.

U.S. envoys intend to warn their longtime ally that they believe his power is quickly ebbing, and that he must lift the 2-week-old emergency decree and work with former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto and other opposition figures to stabilize the country. Underscoring the warning will be an implied threat that if he doesn’t take such steps, Washington is ready to work with others who will, officials said.

The new tack reflects the Bush administration’s belief that even a weakened Musharraf remains their best bet, but that greater pressure and appeals to others within Pakistan are needed to elicit his cooperation. As part of their efforts, the Americans may appeal directly to Pakistan’s powerful military, calculating that influence from Musharraf’s officer corps is vital to ending the widening political chaos.

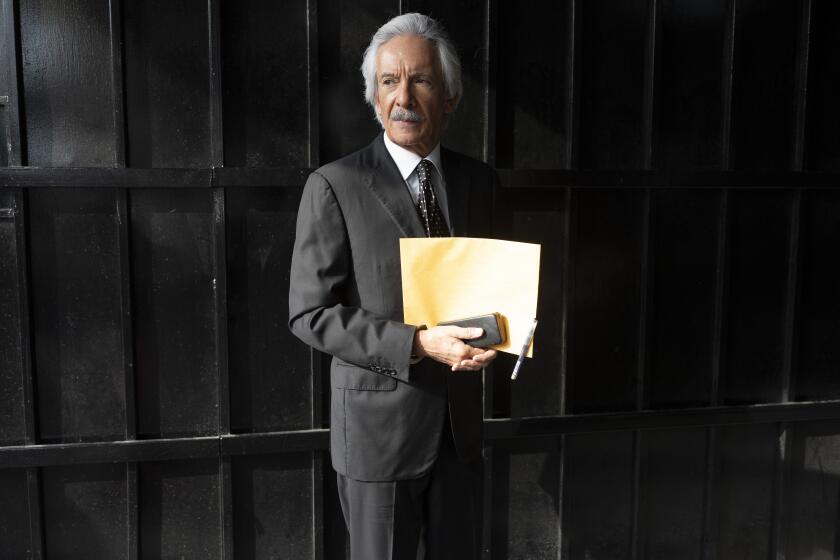

Deputy Secretary of State John D. Negroponte, who arrives in Pakistan tonight to deliver the tough new message to civilian and military leaders, said Thursday that the political process in Pakistan had been “derailed.”

“Our message is that we want to work with the government and the political actors of Pakistan to put the political process back on track as soon as we can,” Negroponte said in Mali, at the end of a four-nation tour in Africa.

In addition to meeting with Musharraf, Bhutto and Foreign Secretary Riaz Mohammad Khan, Negroponte will see Vice Chief of the Army Gen. Ashfaq Kiani, the No. 2 military official.

Hours before Negroponte’s scheduled arrival, authorities freed Bhutto from house arrest, canceling a detention order issued three days earlier.

The order was intended to prevent her from leading demonstrations against Musharraf’s emergency decree; lifting it was seen as a conciliatory move aimed at appeasing the United States.

Administration officials hope to bring about a Musharraf-Bhutto power-sharing deal. While Washington sees chances for such a deal as sharply diminished, it still represents the best hope for stability, U.S. officials said, describing the new American approach on condition of anonymity.

Bhutto has called on Musharraf to step down, and said she would form an alliance with other opposition political parties. But U.S. officials said that with the political opposition divided, such combinations would be weak, and any workable government would need support from the army.

At the same time, some U.S. officials acknowledge that even if he remains in office, Musharraf is unlikely to regain his prior political standing or influence.

U.S. officials would prefer that Musharraf lift emergency rule before parliamentary elections he has scheduled by Jan. 9 and give up his leadership of the army. But if they fail to persuade him, they said, they could build pressure by withdrawing aid to Pakistan or appealing directly to the military.

Persuading Musharraf may prove difficult. He repeatedly has refused to surrender military power and has alienated Bhutto with mass roundups of her party members and by twice placing her under house arrest.

He also has shown signs of a growing resentment of U.S. influence. The Pakistani army appears to remain loyal to him, although the emergency order has caused some unease in the ranks.

As the crisis has stretched through a second week, questions about Musharraf have begun emerging. One Western diplomat in Pakistan said that Bush administration officials were “losing hope” that Musharraf will remain a viable political force.

But, speaking on condition of anonymity, the diplomat added: “I don’t think they’re going to say, ‘It’s time for him to go.’ They’re going to say, ‘Change.’ ”

Western diplomats in recent days have been alarmed by the combative and even erratic tone adopted by Musharraf, whose popular support has been ebbing since the spring. In a recent televised speech, Musharraf appeared to be sweating heavily, and his tone seemed hostile and defensive.

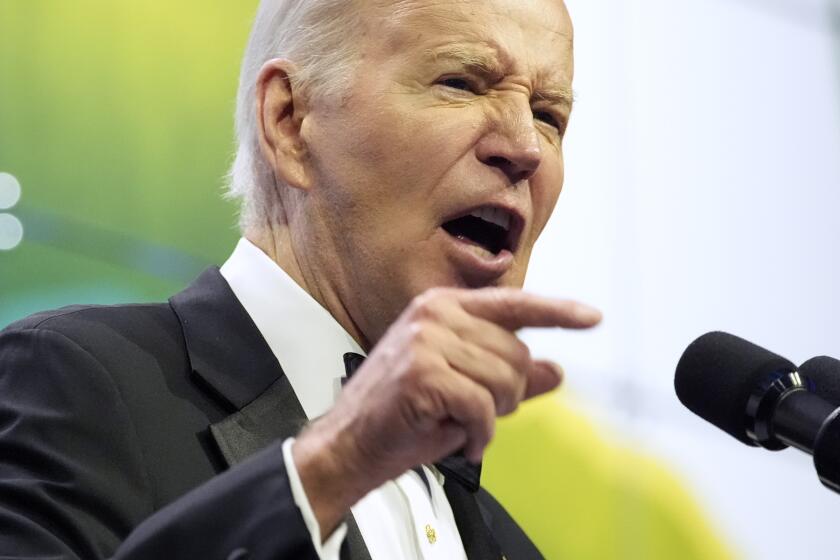

In Washington, officials affirmed their support for Musharraf, even while insisting that it is up to Pakistanis to choose their leaders.

President Bush believes Musharraf has been “a very good ally” to the United States, said Dana Perino, White House press secretary.

She added that there were other “moderate forces in Pakistan” who also want a better future for the country.

The Western diplomat in Islamabad, the capital, said U.S. officials did not believe that a change in army leadership from Musharraf to Kiani would have a negative impact on the fight against insurgents or on the overall political picture.

“Everyone is comfortable with Kiani,” the diplomat said.

U.S. officials said they expect Negroponte’s visit to be tense.

The meeting had been scheduled as part of a strategic dialogue, but officials acknowledged that the purpose now was to allow Negroponte to deliver the White House message that Musharraf needs to step down as army chief, lift the emergency decree and release all political prisoners arrested since emergency rule was imposed Nov. 3.

There is likely to be friction when Negroponte pushes Musharraf to lift the state of emergency before the elections. U.S. officials believe that under emergency rule, Musharraf could manipulate the elections and limit the political gains of Bhutto’s Pakistan People’s Party and other opposition groups.

“That’s likely to be a key point of contention,” said Arif Rafiq, of the New York-based Pakistan Policy Blog.

Many in Pakistan believe that the army may ultimately end the political turbulence, either by pressuring Musharraf to compromise or by replacing him with a civilian president.

Pentagon officials say the two Pakistani army leaders with whom U.S. officials have had the closest dealings, aside from Musharraf, are Kiani, his likely successor as the service’s top officer; and Gen. Tariq Majid, the chairman of the Pakistani Joint Chiefs of Staff.

“The army is into everything in Pakistan. . . . It’s the institution that’s maintained stability in the country since probably the opening days,” said a senior U.S. military official who works with the Pakistanis. “The army has a very vested interest in continuing stability and security in the country.”

One of the difficulties of trying to keep Musharraf in power is that the administration knows it cannot afford to be seen as trying to manipulate the Pakistani political system. U.S. officials know that Pakistani political figures are undermined domestically by American support.

In an apparent concession to the U.S. on the eve of Negroponte’s arrival, the government allowed private Pakistani news channels, whose signals had been blocked since the emergency decree, to go back on the air Thursday. The U.S. and other Western nations had demanded that Musharraf lift media curbs imposed as part of emergency rule.

Today, before Negroponte’s arrival, a caretaker government is to be sworn in to oversee the planned parliamentary elections.

The interim administration will be headed by Mohammedmian Soomro, who chairs the upper house of Parliament and is considered a Musharraf loyalist. The national assembly was dissolved Thursday, the last day of its term.

--

laura.king@latimes.com

Richter reported from Washington and King from Islamabad. Times staff writer Peter Spiegel in Washington contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.