‘Cliff’ deal lifts stocks and doubts

WASHINGTON — Despite the huge relief rally on Wall Street, the incomplete resolution of the so-called fiscal cliff will do little to boost the economy but assures an intense budget battle that is expected to weigh on spending and hiring at least over the next few months.

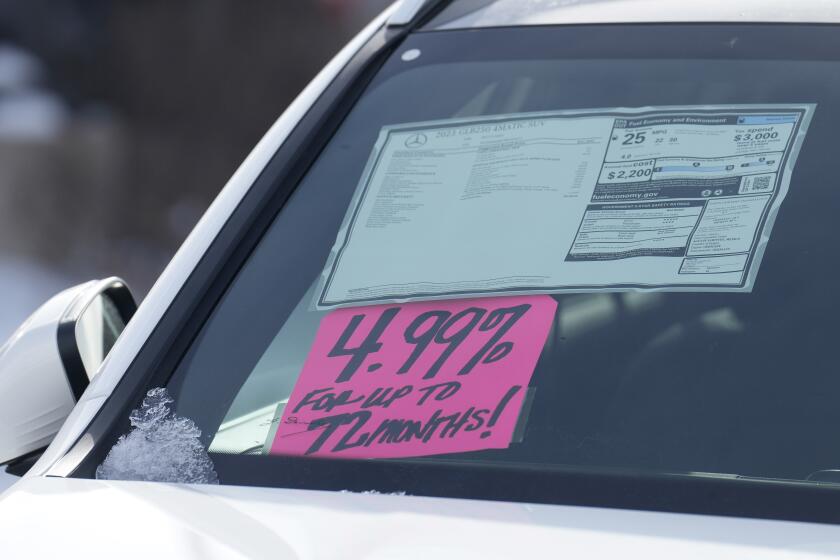

The New Year’s Day deal let payroll taxes for all workers revert to their previous higher rate, though it avoided the worst of the “fiscal cliff” issues by blocking tax-rate increases on all but the wealthiest Americans and postponing federal spending cuts.

That means workers will start seeing on average about $20 less a week in their paychecks starting this month, a cut in incomes that is expected to dampen spending and contribute to slower hiring.

But that’s not what business leaders and economists are fretting about; the payroll tax cut was meant to be temporary, and most had factored its expiration into their new year’s forecast. The big concern is that the deal did nothing to reduce government spending and fell short of taking needed steps to stabilize the rising U.S. debt.

Lawmakers also left for the new Congress the hard work of raising the nation’s debt limit before the end of February, the rough deadline for action in the latest Treasury Department estimates.

Policymakers still must try in the next two months to replace $1.2 trillion in automatic spending cuts over the next decade with a package that would cause less economic damage.

And the fates of many tax deductions and loopholes are up in the air because overhauls of the individual and corporate tax codes are expected to take place this year as part of a deficit-reduction plan.

Wall Street, however, rejoiced. In the exuberant first day of trading in the new year, the Dow Jones industrial average surged 308 points, or 2.4%, to nearly 13,413. The rally gave the Dow its best day since Dec. 20, 2011.

“There’s relief that something got passed that was better than the worst-case scenario,” said Doug Cote, chief investment strategist with ING Investment Management U.S.

But he called the rally one of “false relief” because the longer-term deficit problems remain an unresolved threat.

“There’s still plenty of uncertainty, unfortunately, that remains,” said John Engler, president of the Business Roundtable, a group of top corporate chief executives.

The group’s quarterly survey last month projected the economy would maintain roughly last year’s mediocre growth of 2% in 2013, and Tuesday’s deal probably won’t change that forecast much, he said.

Still, Engler said: “You can certainly say the potential for some harm was averted, but the potential for greater certainty still lies ahead.”

Some analysts say prolonged uncertainty — coupled with the loss of consumer spending from higher payroll taxes — could hold back employers from hiring and spending as they wait for Congress to make more decisions about the budget.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics will release employment numbers for December on Friday, and economists are generally expecting continued steady growth of about 150,000 jobs, a decent number that would slowly bring down the unemployment rate.

But that report may be the best for months ahead if reduced demand and concerns about the upcoming budget fight cause businesses to pull back.

“The cautiousness on the part of businesses will persist,” said Michael Gapen, senior U.S. economist at Barclays in New York. He reckons that the biggest hits to the labor market may be in the first quarter when companies purge payrolls after the holiday season.

The deal did extend emergency unemployment benefits for some 2 million long-term jobless workers who faced an abrupt end to their economic life support, providing about $30 billion in aid that would be pumped directly into the economy.

It also permanently fixed the alternative minimum tax, which threatened to hit millions of middle-income Americans because the provision, which was enacted in 1969 and aimed at making sure the wealthy paid some taxes, had not been indexed to inflation.

Businesses, too, expressed satisfaction with some parts of the tax agreement. Congress permanently extended much of the George W. Bush-era tax cuts, which gave companies clarity on income tax rates.

The legislation also extended the research and development tax credit until the end of 2013 and retroactively reinstated it for last year. And lawmakers extended through this year special rules that allow for accelerated depreciation. The so-called bonus depreciation allows businesses to write off 50% of the cost of capital investments made in 2013, which could help reverse the recent decline in business spending for equipment. Normally, costs are spread evenly over three to 20 years depending on the items purchased.

But corporate executives are worried about a potential default by the U.S. if the White House and Congress can’t agree to lift the debt ceiling.

The executives fear a repeat of the debacle in summer 2011, when a long, divisive fight over the debt limit led to a downgrade of the nation’s credit rating, leading to major short-term damage to investor confidence and economic growth.

Moody’s Investor Services warned Wednesday that the tax deal was not enough to remove the risk of a downgrade of the United States’ credit rating.

The company, one of three major credit rating firms, said the additional $620 billion in tax revenue over the next 10 years from the higher tax rate for wealthy Americans was “a further step in clarifying the medium-term deficit and debt trajectory of the federal government.”

But the package did not produce “meaningful improvement” in the ratio of the federal government’s debt to its economic output. Moody’s said it expected additional deficit reduction measures in the coming months, yet it did not remove its negative outlook on the U.S.’ AAA rating.

Moreover, Moody’s raised particular concerns that the tax deal did not include an increase in the nation’s debt limit. The U.S. technically hit its $16.4-trillion debt limit Tuesday, but the Treasury Department said it could manipulate the nation’s finances to allow for continued borrowing for about two months.

“Although Moody’s believes that the debt limit will eventually be raised and that the risk of default on Treasury bonds is extremely low, this confluence of events adds uncertainty to the outcome of negotiations” over spending cuts, the rating firm said.

For now, analysts also don’t see such high risks, nor are they making major revisions to their economic growth projections for this year.

Most economists are sticking with their forecasts of weak growth in the first half of this year — but no recession — with acceleration in the second half.

The higher tax rates for individuals making more than $400,000 and for couples making more than $450,000 a year are not expected to have a big effect on overall consumer spending. Analysts said these high-income households were more likely to lower their saving rate than their consumption.

And for small businesses paying individual income taxes, the increase in the top marginal tax rate probably is not big enough, by itself, to blunt expansion by the more successful operators, economists at UBS Investment Research said.

But one big question is how much and for how long most consumers will pull back in the face of higher payroll taxes and the uncertainty over federal spending cuts.

“From my standpoint, it’s a little painful,” said Rosalind Gibson, a lawyer in San Diego County. “It means I’ll probably take one less vacation than I might, but it won’t affect my daily ability to buy groceries and put gas in my car.”

Economists and business leaders seemed wistful that more didn’t come out of the deal, saying it was a lost opportunity for an economy stuck in low gear for the last three years. With the housing market recovering, job growth improving and the global outlook looking better, the ingredients were in place for 2013 to be a potentially breakout year of stronger growth.

Tuesday’s deal “was a minimalist agreement,” said Gary Schlossberg, senior economist with Wells Capital Management in San Francisco. “The budget will continue to dominate the first half of the year, overshadowing stronger fundamentals.”

Times staff writers Andrew Tangel in New York and Alana Semuels in Los Angeles contributed to this report.