Obama’s in Asia with Pacific trade partners, but the pact depends on his sales job back home

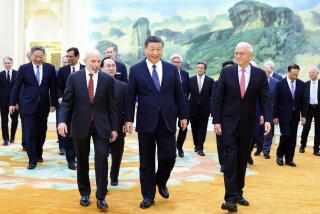

President Obama, center, talks with Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto as other leaders of the Trans-Pacific Partnership countries stand for a group photo in Manila on Wednesday.

The victory lap President Obama wants to take in Asia this week over a sweeping Pacific trade deal stands to be dampened by frustration among some of his chief allies back home: organized labor.

Leaders from the 12 participating nations that signed off on final terms of the Trans-Pacific Partnership last month appeared together here for the first time Wednesday to mark the deal. The Obama administration counts the pact as a centerpiece of its strategy of rebalancing U.S. military and diplomatic resources toward Asia, where China has become increasingly assertive.

After waving to cameras and posing for a photo, the group sat down to plot its next steps toward enacting the deal, with Obama aware that his domestic sales job, perhaps the most difficult among the group, is the linchpin to its success.

“Execution is critical,” the president said of what he again called the “the highest-standard and most progressive trade deal ever concluded.”

“This is not easy to do,” he noted. “The politics of any trade agreement are difficult.”

Other TPP member countries, including Japan and Malaysia, face tough domestic opposition to the trade deal as well. But they will wait for U.S. lawmakers to vote on the pact, possibly as early as next spring, before trying to win support for it themselves.

Without approval in the U.S., the deal, encompassing 40% of the global economy and a quarter of the world’s trade, would fall apart. China isn’t a party to the U.S.-led trade pact, which was concluded in October after more than five years of negotiations.

Since details of the agreement were released two weeks ago, the reaction from congressional Republicans has been fairly muted. But opponents of the deal, including unions and liberal Democratic lawmakers, have voiced strong criticism of the agreement, including the provisions on labor.

The White House has stressed that the deal would provide unprecedented protection for workers and that it would grant extraordinary access to union organizers during negotiations, but labor leaders said the final agreement not only fell short of what they’d expected from Obama, but is in some ways a step backward.

They argued that the pact includes little to ensure that American workers would stay competitive against competitors abroad and that such a shortcoming showed that U.S. mediators failed to learn the lessons of past labor deals that hurt rank-and-file union members.

“It’s quite possible to say these are the highest labor standards ever,” said Celeste Drake, trade and globalization policy specialist at the AFL-CIO. “If they’re built on a foundation that hasn’t worked to defend labor rights, you’re putting another story on a building that’s falling into the quicksand.”

Administration officials are eager to contest the accusation, even as they readily concede that they may not win over a constituency that is otherwise often a loyal Democratic ally.

Mike Froman, the U.S. trade representative who served as chief negotiator for the administration, carries with him a long list of requests labor had made and can point to provisions in the final document that satisfy many — some even going beyond what unions sought.

“On the vast majority of issues they’ve raised, we’ve gone to the negotiation table and delivered,” Froman said. “No group got 100% of what they wanted, and that’s just the nature of negotiations.”

Members of the administration and the minority of congressional Democrats who support the agreement have been quick to point

to the key role they said

labor helped play during the talks.

In regular consultations, labor leaders made clear their demands on a range of issues that would potentially cement or kill the deal. Administration officials in turn brought most of those concerns to the trade discussions to reflect the political pressures they had to contend with.

Vice President Joe Biden, in particular, would press foreign leaders over how little the U.S. could give up on certain agreements if it hoped to maintain the fragile coalition of Democrats and Republicans needed to ensure passage of the trade pact, according to officials involved in the discussions.

Labor officials and skeptical Democrats don’t dispute that they were involved in the process but said it became clear as the talks reached a crucial point that their influence wasn’t necessarily valued.

“From what we’ve been able to discern, the changes that have been asked for by members of Congress, by public health, human rights, consumer, labor, religious and environmental organizations have not been made,” said Rep. Rosa DeLauro (D-Conn.), who is leading an effort to defeat the pact when it comes to a vote.

DeLauro and other congressional Democrats had pressed especially hard for provisions to thwart countries from using their currency exchange rate to gain an unfair advantage in trade. The issue isn’t addressed in the pact, though the Obama administration engineered a separate side deal aimed at preventing currency manipulation.

Among the examples labor in particular points to is an implementation plan for Vietnam, one of the key members of the new trade alliance, that gives that nation five years to establish a new independent labor federation even after it would begin freer access to U.S. markets.

“Now is the time when the countries can be asked to do the most,” the AFL-CIO’s Drake said. “It’s hard to believe that ... five years from now, that the U.S. is then going to have the oomph to go ahead with a

labor case because there will be a lot more commercial pressure not to.”

Officials see this as a case of the administration being judged overly harshly. They point to the prosecution of a trade case against Guatemala, for instance, even under the lower standards of the Central American Free Trade Agreement, and steps taken to enact legislation to increase trade enforcement powers.

Obama is leading an all-out administration effort to sell the deal to the public, as was the case last summer in a pitched battle over legislation that was a key precursor to final negotiations.

A war room — the White House calls it a campaign center — has been relaunched to beat back efforts to derail the deal and reassure any lawmakers wavering on the agreement.

Before he left the U.S. on his 10-day international trip, the president at several public events promoted the TPP’s potential benefits for small businesses and used a bipartisan collection of foreign policy experts to reinforce his contention that the deal holds national security as well as economic ramifications.

Obama plans a major speech on the trade pact in Malaysia in the coming days at another regional summit, one that includes both TPP-member nations and others, such as the Philippines and South Korea, that have quickly signaled interest in joining its ranks.

Asked about whether he had concerns about Obama’s ability to deliver the trade deal at home, President Benigno Aquino noted that the Philippines soon faces its own campaign season.

“We recognize the pressure to make [popular] statements at this point in time,” he said. “At the end of the election period, there will be sobriety.”

michael.memoli@latimes.com

Times staff writer Don Lee in Washington contributed to this report.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.