After police killing of a Zapotec man in Salinas, questions about a language barrier

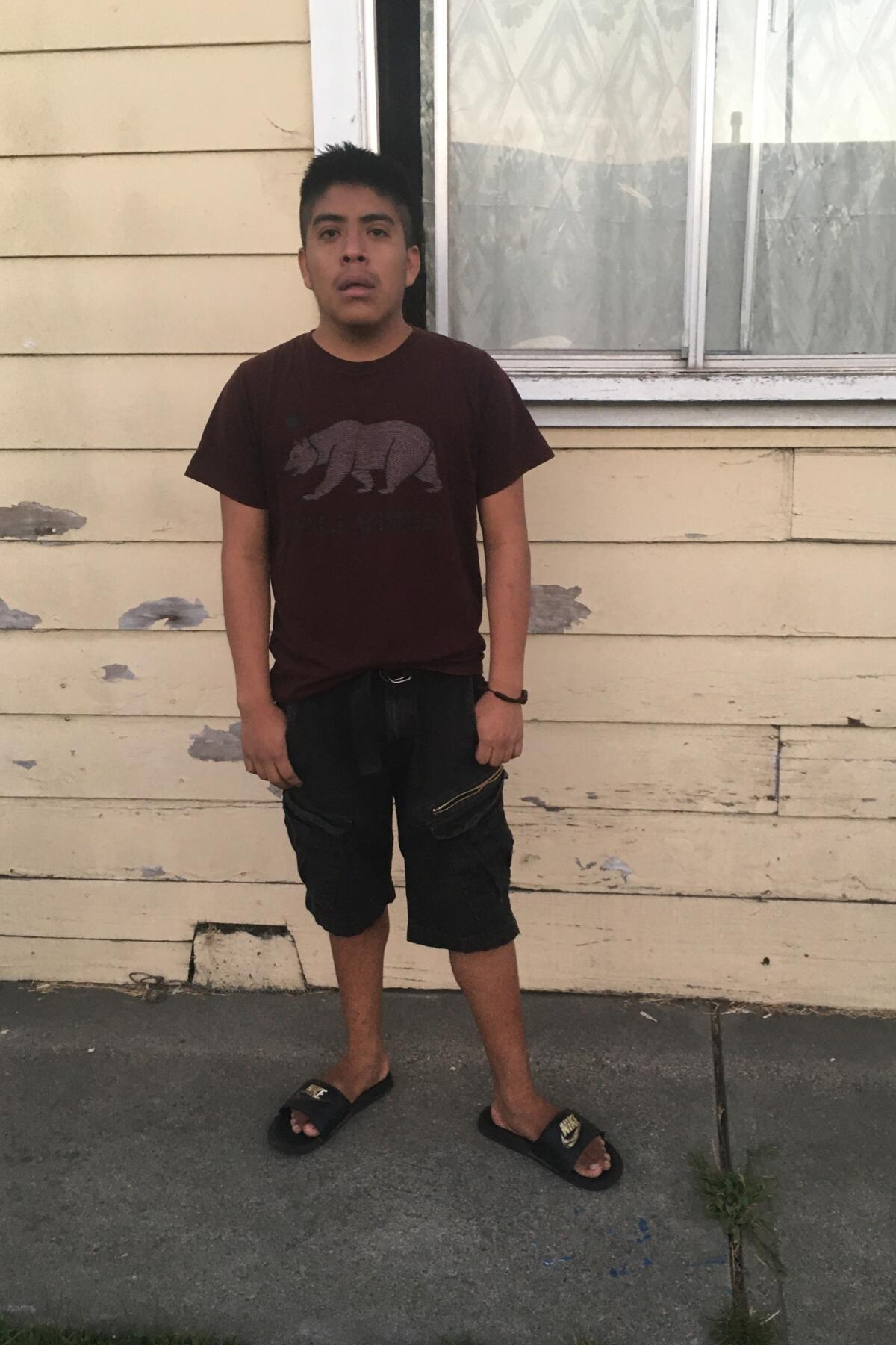

After the killing last week of an Indigenous Mexican teen by police in Salinas, advocacy groups are concerned that language barriers may have played a role in the fatal encounter.

Gerardo Martinez, 19, who spoke the Mexican Indigenous language Zapotec, was shot about 8:30 last Friday night when officers responded to his home and tried to communicate with him in Spanish, according to the Monterey County district attorney’s office. Prosecutors contend Martinez also spoke conversational Spanish.

A neighbor called 911 shortly after eight to report that Martinez was “really drunk” and had pointed a black handgun at him, officials said. On the same call, the neighbor later said that the weapon might actually be a BB gun and that he thought Martinez could be under the influence of methamphetamine.

In minutes, officers were at the scene. The officer who ultimately shot Martinez positioned himself with a rifle behind his patrol car, about 50 feet from Martinez’s home, according to the district attorney’s office. Officers unsuccessfully tried to determine Martinez’s phone number.

When Martinez partly exited a side door of his home, officers ordered him in Spanish to come out with his hands up, the D.A. account said. Instead, according to the D.A.’s statement, Martinez walked in and out of the side door several times while officers continued issuing commands.

Drone footage released by prosecutors, which doesn’t contain sound, shows Martinez opening and closing the side door several times to peer outside. In one instance, he held what was later found to be a BB gun and what appears to be a canned drink.

The shooting occurred when Martinez re-emerged from the door and raised the gun. According to the district attorney’s office, he had pointed the weapon at an officer, who fired three rounds from a rifle, striking Martinez in the torso. He died shortly thereafter.

District attorney’s officials said police recovered a “real-looking” BB gun next to Martinez. They added that the state Department of Justice, which is mandated to investigate fatal police shootings of unarmed civilians, declined to investigate because it considered Martinez to have been armed.

Sherri Hall, a spokesperson for the district attorney’s office, said that officials were investigating whether the 911 caller’s information that the weapon could be a BB gun had been relayed to police.

On Thursday, Latin American Indigenous advocacy groups from across the state issued a joint statement saying that Martinez did not speak English and had a limited understanding of Spanish. They’ve called for training for Salinas police officers to better understand and communicate with Indigenous people and for the state to investigate the shooting.

“As a monolingual Zapoteco speaker, he did not understand the commands to come out of his home and to raise his arms,” they said.

The Salinas Police Department did not respond to a request for comment. Hall said that no interpreter had been requested Friday night.

“We now know the deceased spoke conversant Spanish based on a body-worn camera from a prior contact with law enforcement,” she said when asked about the language barrier claims. She declined to provide more information about that encounter.

There is no census count on the number of indigenous people from Mexico and Guatemala living in California, many of whom may have only a basic grasp of Spanish. A 2010 study by farm labor researchers and a nonprofit estimated there are 165,000 Indigenous farmworkers and family members in the state — a projection based on interviews with people from hundreds of Mexican hometowns as well as data from a U.S. Department of Labor survey.

Advocacy groups have for years raised concerns about police departments’ ability to interact with Indigenous people. In 2019, CIELO, a local organization whose Spanish acronym stands for Indigenous Communities in Leadership, partnered with Los Angeles police to provide pocket cards for officers that can help them identify an Indigenous-language speaker and, if necessary, call an interpreter. The initiative grew out of cultural awareness trainings Indigenous Mexican community leaders held for LAPD officers after the 2010 fatal shooting of an Indigenous Maya man who spoke K’iche’.

Police in Oxnard have also partnered with the Mixteco/Indígena Community Organizing Project, a nonprofit that works with Indigenous communities in Ventura and Santa Barbara counties. The group’s executive director, Arcenio Lopez, said that in trainings, officers are taught, for example, that Indigenous migrants may avoid making eye contact with police as a sign of respect.

“These are populations that are in constant fear in law enforcement because of previous experiences in their own countries — there is no trust,” he said. “We’re trying our best.”

Martinez moved to the U.S. from the small town of San Vicente Coatlán in the Mexican state of Oaxaca. A GoFundMe to help bury Martinez has grown to more than $13,000.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.