Joan Didion’s California captured in sweeping new collection

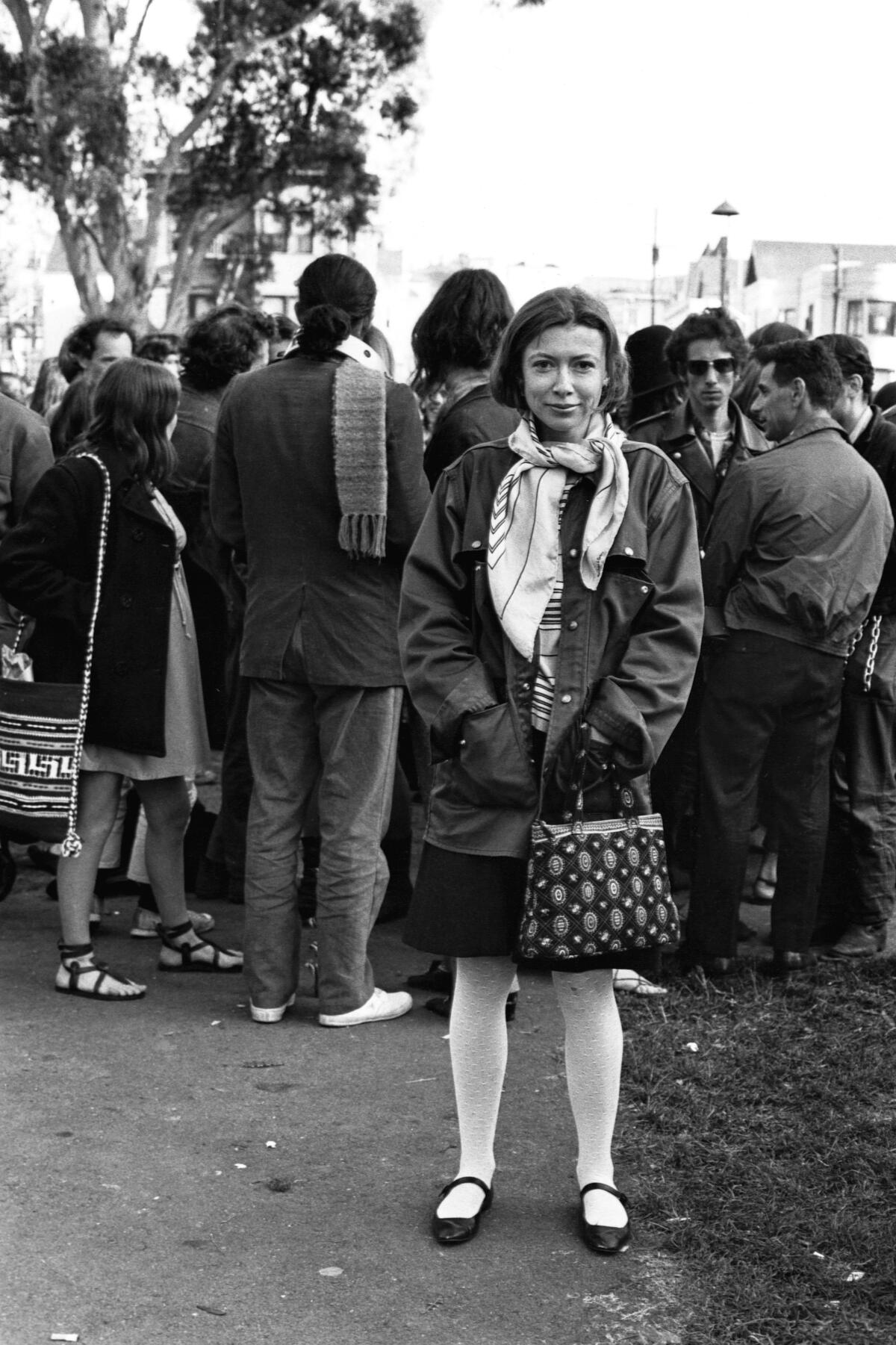

The sequence is as predictable as the season itself: The calendar reads “fall” but the thermometer registers 90-plus. The Santa Ana winds kick up. Wildfires zipper across the landscape. Once again Joan Didion whispers in the Southland’s collective ear.

“I have neither heard nor read that a Santa Ana is due, but I know it, and almost everyone I have seen today knows it too,” she writes in “Slouching Towards Bethlehem.” “We know it because we feel it. The baby frets. The maid sulks. ... To live with the Santa Ana is to accept, consciously or unconsciously, a deeply mechanistic view of human behavior.”

Novelists, essayists and poets, photographers and painters have all evoked the region in its inscrutability and calamity, but Didion’s measured cadence is embedded in our consciousness. Tropes become burrs. We come to her for dusty palms, pepper trees, eucalyptus, the “soft westerlies off the Pacific,” but also the concrete overpasses, cyclone fencing and deadly oleander.

It’s home. The truth of it. Hot pavement under our feet. She has written hauntingly about disasters — both acts of God and man-made mayhem, from runaway wildfires to Charles Manson — that have rewritten the narrative of this place. Pared down: For many she articulates California’s particular seasons, a West that is as recognizable as it is changeable.

A new collection captures and revisits Didion’s seminal work — both fiction and nonfiction. In the Library of America’s “Didion: The 1960s & ’70s,” readers can feel the prickly heat, smell the approaching catastrophe. Within her clean crisp sentences, this mirage of a destination shimmers up: the soil, the light, a tangle of deeply imperfect humans, all trying their luck, and then gone in a moment.

Edited by former Times book editor David L. Ulin, the volume assembles five titles — “Run River,” “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” “Play It As It Lays,” “A Book of Common Prayer” and “The White Album” — that established Didion as one of the requisite voices not just of the West but of her moment. The collection is the first of three planned volumes dedicated to her work.

In the first edition, “What we’re seeing is the emerging her as a writer, and also in some ways as a cultural figure ... in [her] own right,” Ulin says in a recent interview.

Weaving together intimate autobiographical elements, keen sensory observation, topical themes and major cultural shifts (or rifts), Didion arrives as a distinct voice in the era of New Journalism. Looking both forward and backward, she assesses the vanishing California Dream and investigates what might lie in wait around the corner.

“All this stuff is happening in California,” Ulin says. “And as a native Californian from a particular strata of society, she’s bringing a kind of California sensibility that if you’re not from California, you may not have ever seen it. That creates a really complicated overlay of the perspective, and that is where the work begins to exist in a way that no one else is doing.”

Readers carry Didion around in different ways, for different moments, and this new book is a defining compilation of her early writing. The oft-mimicked coming-of-age essay “Goodbye to All That,” about Didion’s early love affair with New York City as dreamscape, serves as a well-fingered pocket talisman. It’s a reminder that we can outgrow a place, or it us. (“It is easy to see the beginning of things and harder to see the ends.”)

In another essay, “Some Dreamers of the Golden Dream,” Didion casts a hard, harsh light on California’s dark passages hidden amid the lush flora, where people let go of their reason in pursuit of their desire: “Here is the last stop for all those who come from somewhere else,” she writes, “for all those who drifted away from the cold, from the past, and the old ways ... trying to find it in the only places they know how to look: the movies and the newspaper.”

Born in Sacramento in 1934, Didion is a fifth-generation Californian. A curious reader and writer at an early age, by 13 she picks up Hemingway’s “A Farewell to Arms” and “retypes the first paragraph to get inside the language and see what makes it work.”

After shuttling back and forth across the country with her Army Air Corps father and her family, she eventually enrolls at UC Berkeley and joins the staff of the Daily Californian. While there, in 1955, she applies for a job in New York City to participate in Mademoiselle magazine’s summer guest editor program. It opens a new chapter — three years later she moves to New York, working at Vogue and Mademoiselle. Through a mutual friend, she meets, and later marries, writer John Gregory Dunne, and is pulled back West — back to California in 1967, amid the 1960s flashpoint. They settle in Los Angeles, and it becomes a rich vein of subject matter.

Her first book, the novel “Run River” — a portrait of old-guard pioneer families, backdropped by the ranch valleys of her native Sacramento — is met with mixed reviews and lackluster sales. But her first collection of essays, “Slouching Towards Bethlehem” — whose title essay considers San Francisco’s counterculture movement, its goals and its casualties — is greeted with gravity; in his New York Times review, Dan Wakefield praises it as “a rich display of some of the best prose written today in this country.”

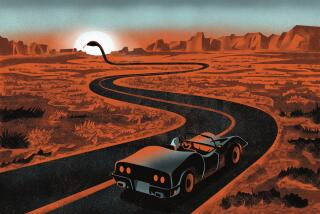

In 1970 Didion publishes her second novel, “Play It As It Lays,” which also receives “rapturous reviews.” Those two titles and a Time magazine photograph by Julian Wasser of Didion — sylph-like, standing with her Corvette, smoking, eyeing the camera with a flare of provocation — become “the first iconic images of her,” Ulin writes.

When Didion addresses the reader in that confiding second person, those eyes peer, unblinking, at you. It is a writer’s seduction, a reporter working the moment to get at the most uncomfortable truth.

She writes about the treks and dead ends of various iterations of “pioneers” and “gamblers,” both actual and metaphorical, as she drifts through a rarefied world of Beverly Hills lunches and peau de soie dresses and the scent of eau de Joy. As an interlocutor/reporter she may have been perceived as “temperamentally unobtrusive,” which, as she’s famously written, she used to her advantage.

But on the page her presence is striking and indelible, and it has been scrutinized and critiqued. Didion is indeed her own atmosphere and terrain.

Some have called out and denounced threads of class caste in her writing. “I think we absolutely have to consider that when we’re reading her work,” Ulin says. “There are a lot of readers who have been turned off to her writing because of those issues. But one of the things I admire is that she makes no bones about owning it. She is writing from a very particular and very rarefied social and class-based perspective.”

These early works, the essays especially, have become a key part of Didion’s construction of persona, Ulin says. “[The essays] move [her] out of her experience. She becomes more of an external observer. That’s where we start to really see the development of that cool, ironic sensibility. That edge of distance.”

That distance is sometimes read as aloofness: “One of the things we tend to overlook when we talk about her as a cultural chronicler is that she’s always writing from her own inner weather. Her inner weather is not the cliché of the ‘sunny California.’ She’s got a dread point of view,” Ulin says. “The things I admire most are her tiny universals, the precision of the language, the beauty of the language, the kind of skepticism of the point of view. The sort of questioning of everything, particularly the kind of received narratives.”

For a region that to the outside world remains gauzy or improbable — still in many ways a mirage — Didion has worked to pin the complexity of Los Angeles, and by extension the West, on the page.

“Why did I write it down,” Didion asks herself, in “On Keeping a Notebook.”

Why might any of us?

“In order to remember.”

George is the author of “After/Image: Los Angeles Outside the Frame” (Angel City Press), and won a 2018 Grammy for her liner notes for “Otis Redding Live at the Whisky A Go Go.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.