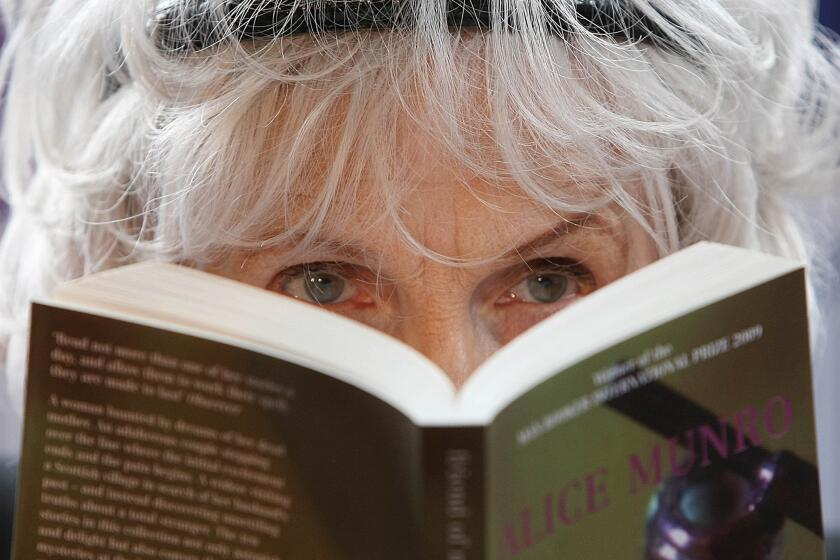

Margaret Atwood’s guide to turning dark histories into fictional futures

On the Shelf

The Testaments

By Margaret Atwood

Anchor: 448 pages, $16.95

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

The grim dystopia “The Handmaid’s Tale” provides no hint of how delightful Margaret Atwood can be in conversation. Her humor is dry, her perspective vast. Atwood classifies much of her work as speculative fiction, our world transformed by events that stem from our present and past. That’s how the totalitarian religious state of “The Handmaid’s Tale” came about in 1985 — and how the MaddAddam trilogy, completed in 2013, imagined a devastating pandemic, survived by a few humans and a number of bio-hacked animal creatures.

“The Handmaid’s Tale” has, of course, been adapted by Hulu, featuring Ann Dowd as the fearsome Aunt Lydia — a villain who takes on a more ambiguous role in that book’s much-belated sequel. “The Testaments,” which won a Booker Prize, is out in paperback this fall. Adept at new technology at age 80, Atwood is also a keen student of history — the better to warn us of where we are going. Below are excerpts from a recent conversation ranging across global crises past, present and future.

“The Testaments” has three women telling their own stories, and that often humanizes a person. Aunt Lydia thinks she’s humanizing herself, but she’s also very untrustworthy.

Well, you know, read some memoirs of people. [Laughs.] Everybody prefers to make themselves look good. If you go into accounts of people who have defected from totalitarian regimes, who have been quite high up in that regime — of course they’ve been complicit. If they had been openly resistant, they would have been shot. I don’t know whether you saw “The Death of Stalin,” about all of the successors to Stalin who’ve been totally complicit with what he’s been doing; it’s a power struggle for who’s going to take over. And [police chief Lavrentiy] Beria has got the dirt on everybody ‘cause he’s the KGB, and fully intends it shall be him. But they know that if they don’t kill him, he’s going to kill them. So that’s what they do.

Perhaps no other medium has better helped us process 2020. Our fall books special brings you the books and authors who’ve helped make sense of it.

That idea of secret police holding everybody’s dirty secrets — that is the source of Aunt Lydia’s power. It made me think of the Stasi — how much they used secrets and blackmail. You wrote some of “The Handmaid’s Tale” in a divided Germany.

Of course it was one of my models. When I was living in West Berlin, I also went to East Berlin, which I could do with a Canadian passport quite easily, although Germans couldn’t. And I went to Czechoslovakia and I went to Poland. In East Germany there wasn’t really anybody I could talk to. I could talk to people in Czechoslovakia, but only in the middle of the park. Poland, on the other hand, was already pretty wide open because they had a strong opposition, the Catholic Church. They couldn’t kill everybody who was in the Catholic Church; there were too many of them. Now that country has gone pretty right wing. Which often happens when there has been a regime calling itself “left” and it’s been corrupted. But they do pretty much the same thing. [Laughs.]

In 2017 you came to the L.A. Times Book Festival for a preview of the show. One of the things you said, referencing the Women’s March, was, “In a democracy, when you’re still allowed to have protest marches without getting shot and arrested …” — Trump has since had the feds going into Portland, threatening intervention elsewhere.

I’ve been looking at this with great trepidation. But so far it’s only been a few people who’ve been shot and arrested. There has been enough pushback so that has been somewhat damped down. Would-be authoritarian leaders try it on to see if there’s any pushback. There’s still voting in the United States. Cherish it. One thing these people like to do is create chaos. And then you say, I’m going to fix the chaos. Not pointing out that, in fact, you’ve created the chaos in the first place.

Hulu’s dystopian “The Handmaid’s Tale” launched Wednesday to critical plaudits — for author Margaret Atwood, for lead actress Elisabeth Moss and her costars, and for the couldn’t-have-done-it-better timing of the streaming service’s latest offering.

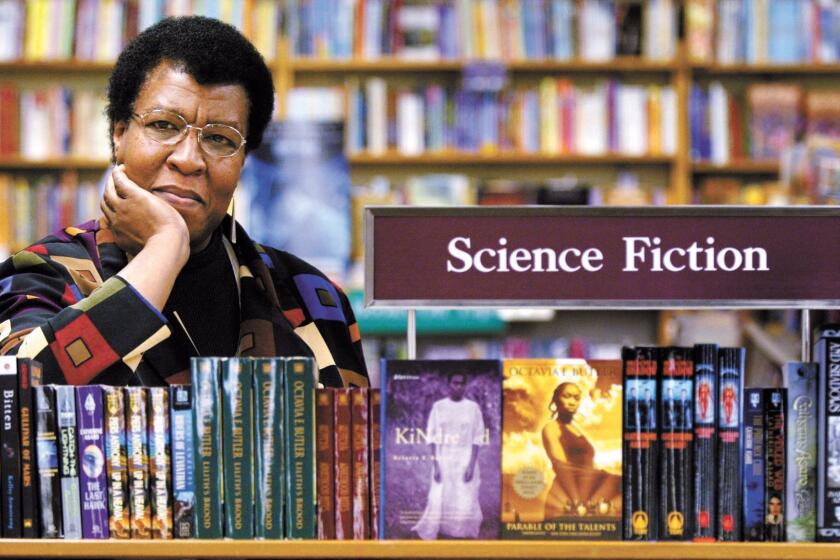

So as a writer of speculative fiction, you extrapolate from the news, you go back to old clippings. I read Octavia E. Butler’s “Parable of the Sower” for the first time during the pandemic and she worked in a similar way. Did you and she ever cross paths?

No, alas, I didn’t know her. But I’m not surprised she did that because it’s the same thing that Orwell was doing in “1984.” It is the same thing that [Yevgeny] Zamyatin was doing in his novel, “We,” in 1923. He practically lays out what Stalin was going to do. It’s creepy. But he was watching, he had been an old Bolshevik. All speculative fiction writers are writing about the present and the past, and they’re saying: If you keep going along this road that we’re on, here’s where you’re likely to end up.

“The Testaments” and “The Handmaid’s Tale” feel like history too — they’re made up of witness documents.

Right. How do we know what we think we know? I’ve just been reading “The Decameron” and it begins with an introduction which describes the plague. [Boccaccio] begins by describing what it was like in Florence during that plague; it’s from eyewitness accounts like that that we even know what happened. And documents that people were writing during Nazi Germany and hiding. So I have Aunt Lydia creating a secret document that she’s going to hide; if anybody of the regime reads it they will of course destroy it.

And probably her.

Oh, absolutely. Well, we won’t give away any plot points. But that is the risk she is taking. A lot of people took those risks. One of my favorites is Anna Akhmatova, a Russian poet, who wrote a poem called “Memorial” about the Stalin purges. She knew that if she was caught with it, she would be killed. She got her friends — each one memorized a part of it. She destroyed any paper copies, and they were the repositories of this poem. When the Stalinist era was over, they got together and recited their part, and then it was published. It became a spearhead of the anti-Stalinist movement.

Your books seem preoccupied with two threads of dystopia: patriarchy and climate destruction. Is there a connection there?

It’s about money. I just came across this quote today: The people who are easiest to fool are people who want to be fooled. So it is much more comforting to believe that none of these things are happening: there is no COVID, there is no climate change, there is no racial inequality, there is no kleptocracy. That’s comforting. It just happens not to be true. But people can live all their lives in the state of untruth. It’s just more comforting. But then it’s not comforting when it impacts you and you die. If the oceans die, so do we. So that’s my last message, which is: You better fix that. If you want a human race. If you don’t, be my guest. I won’t be there.

The Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens has announced a one-year fellowship in honor of sci-fi author Octavia E. Butler.

Kellogg is formerly books editor of The Times.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.