How a project to honor artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres devolved into an Instagram stunt

The invitation came early in May. Well before cities across the United States erupted in protest against the brutal killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. But at a moment when the pandemic in the U.S. was grinding into its third month, unemployment had hit a staggering 14.7%, and it was becoming clear that COVID-19 was taking the lives of the poor and under-represented at higher rates than anyone else.

Along with many others, I was being invited via email to participate in a collective recreation of a 1990 installation, “Untitled” (Fortune Cookie Corner), by the late Cuban artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres. The original piece consists of a mound of fortune cookies, generally piled on the floor against a wall or in a corner. The public is then invited to consume the art. As visitors take the cookies, the pile is continuously replenished. In its original guise, “Untitled” employed approximately 10,000 cookies.

The piece was one of a series of installations by the artist — who created similar piles out of chocolate and hard candy — that evoked cycles of depletion and regeneration. They are works that drew from the mortal tumults of the AIDS crisis, reflected in pieces with titles such as “Untitled” (Placebo) and “Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A.), which paid tribute to the artist’s partner, Ross Laycock, who died from AIDS-related complications in 1991. Gonzalez-Torres was claimed by the disease in 1996 — at age 38.

Digital-art memorials to George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery and other black victims of white violence are rallying cries for social justice.

In this new version of the installation, orchestrated by Andrea Rosen Gallery and David Zwirner (the two New York galleries that represent the artist’s estate), 1,000 “diverse invitees” around the world were asked to create smaller fortune cookie piles of between 240 to 1,000 cookies — cookies we would have to acquire and pay for ourselves. Together, the email said, these would “become an active part of the total ‘site’ of an expansive physical exhibition.”

Naturally, there was a social media-ready hashtag that includes the emoji for a fortune cookie.

Since March, when many U.S. cities began to go under informal quarantines, writers and activists have examined the comparisons between the COVID-19 pandemic and the AIDS crisis of the 1980s and ‘90s. (Masha Gessen features an excellent round-up of these stories in a New Yorker essay.)

I too have thought a lot about that era. For several years, when I lived in New York City, I served as a volunteer at Gay Men’s Health Crisis. My first meeting with the client I served during that time took place at an AIDS hospice. The other night he came to me in a dream, as if he were reaching out to me from one pandemic into another.

COVID-19 has Thom Mayne, Michael Maltzan, Barbara Bestor, Rachel Allen and more Los Angeles architects rethinking design, from balconies to doorknobs.

Which is to say that I’m sympathetic to the instinct to resuscitate a work by an artist who died too young and whose installations serve as poignant mementos of loss — but also as cheeky reminders of the thrill of living. Those candy piles, wrote Randy Kennedy in the New York Times in 2007, when Gonzalez-Torres was posthumously chosen to represent the U.S. at the Venice Biennale, served “as a means for his art and ideas literally to be spread, like a virus — or maybe like joy — by everyone who took a piece.”

But the idea of being asked — er, “invited” — to recreate these pieces in the middle of this pandemic (and in the same month I, like countless other U.S. workers, found myself on a partial furlough) strikes me as tone deaf at best and foolhardy at worst.

There’s the questionable wisdom of asking people to go out and locate several hundred fortune cookies in the middle of a contagion. The alternative of ordering them online seems no better. As Emily Colucci notes on the arts website Filthy Dreams: “Perfect timing during a pandemic when package delivery is overrun and Amazon employees are being dangerously overworked and underpaid!”

Sorry, overtaxed delivery workers without any social safety nets, but this order of 1,000 fortune cookies is ESSENTIAL.

There is also the issue of setting up a work intended to engage the public when public exchange is limited. The conditions for re-creating the piece left the site up to each invitee. Which means many participants have simply installed the cookies in their own homes — and then diligently posted photos to social media.

The result: Felix Gonzalez-Torres as Instagram prop for the art world well-connected.

Since the show launched May 25, the cookies have appeared in lots of tastefully minimal rooms and the account of a dogfluencer. All at a time when the pandemic is exacerbating hunger in the U.S. (The show is scheduled to run through July 5.)

I’m all for the idea that art can offer succor in a time of strife. But in a period of such glaring need, these photo ops feel like fancy pink salt in the collective wound. Perhaps Zwirner and Rosen could use their vast mailing lists to stage an event that would support the myriad relief funds for artists and museum workers.

I took my fortune cookie money and donated it to the Galilee Center, a nonprofit that has been supporting Coachella Valley farmworkers and their families with rent assistance and a food pantry. (My colleague Brittney Mejia has covered the group’s work in The Times.)

The donation was in honor of Felix Gonzalez-Torres.

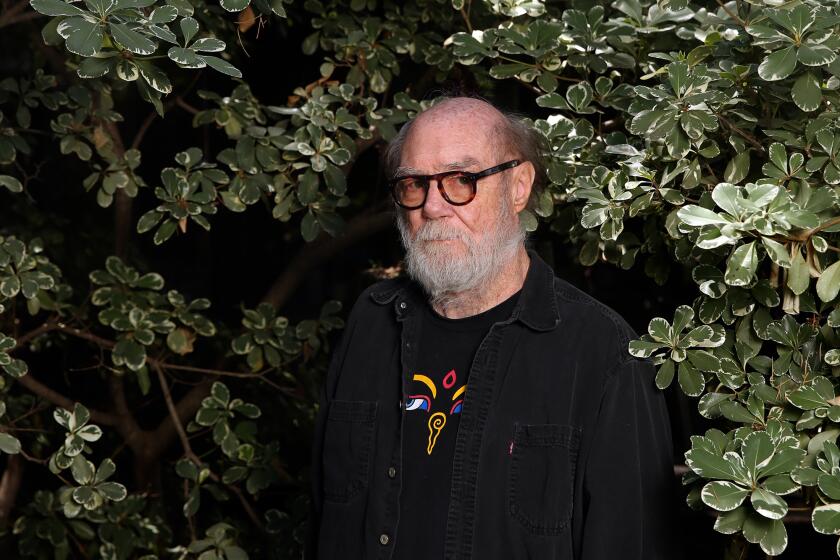

Paul McCarthy’s Hammer Museum solo show shut down for COVID-19. From home, he talks of human nature, violence and turning from performance to drawing.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.