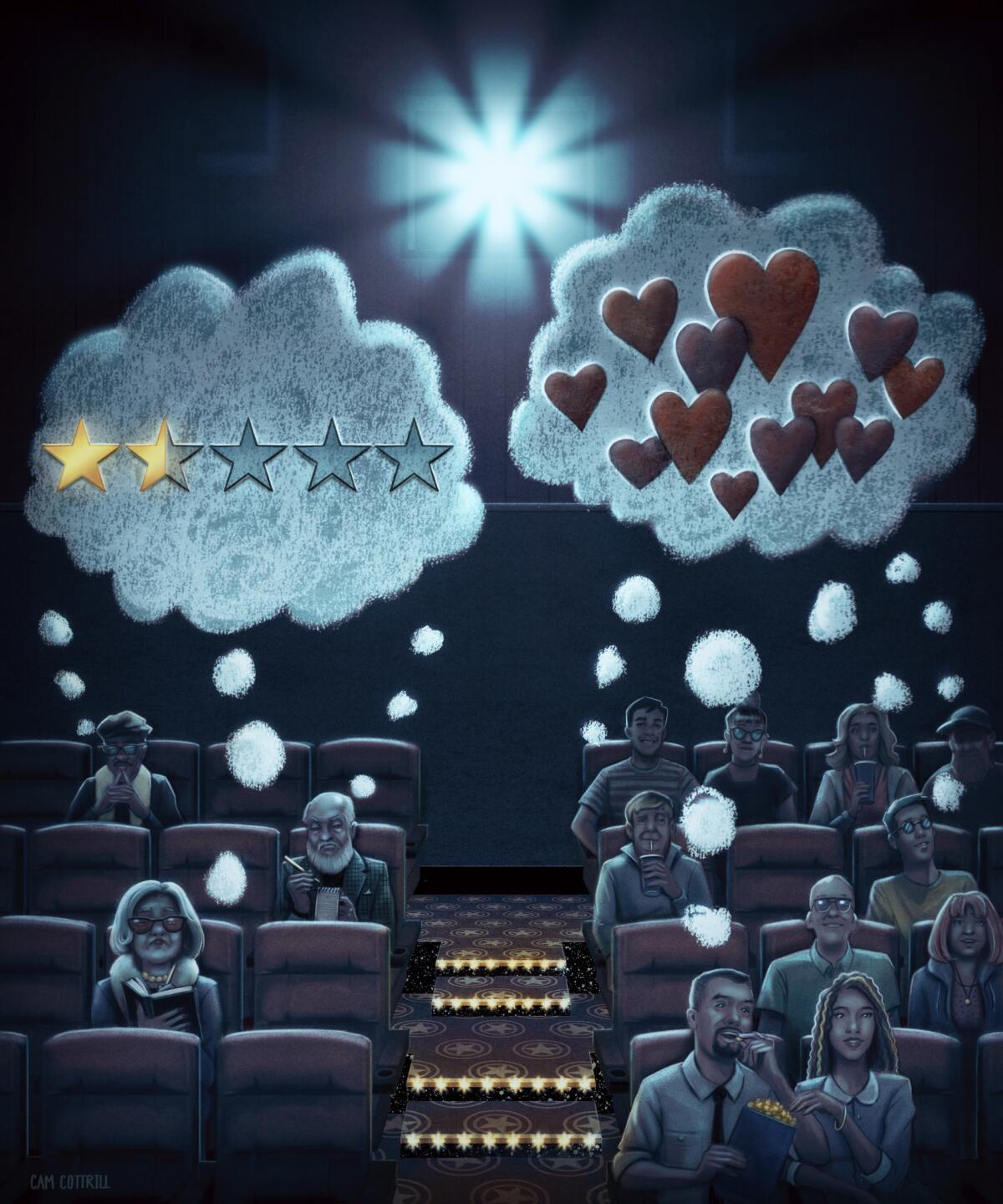

Ahead of the Oscars, a look at what movie critics don’t get right about crowd-pleasers

When Film Comment, the premier movie magazine in America, culled the choices of two dozen critics and editors into a list of the 20 best films of 2018, three of those choices became best picture nominees in this year’s Oscars race: “Roma,” “The Favourite” and “BlacKkKlansman.” Two other Oscar best picture contenders — “Black Panther” and “A Star Is Born” — didn’t make the magazine’s top 20 list but were cited by one or two of the critics. Yet not even one critic mentioned two of the most talked-about best picture nominees: “Green Book” and “Bohemian Rhapsody.”

Those omissions got me thinking about the growing disconnect between film critics and movie audiences, not to mention awards voters. Both pictures won the top prizes at this year’s Golden Globes — “Bohemian Rhapsody” for drama motion picture and “Green Book” for musical or comedy motion picture (it also won the PGA Award for best theatrical motion picture). And both pictures have scored at the box office — particularly the breakout hit “Bohemian Rhapsody” — and earned the affection of millions of viewers. Yet many critics have gone out of their way to slam the films and to disparage the groups that have given them awards.

Well, you might say, it’s nothing new for critics to disagree with the public. But actually, this is something new. Previously, there were always esoteric movies that pleased critics but left the public bewildered. And of course, there were smash hits despised by critics. (“Pretty Woman,” anyone?)

But more often, critics were in sync with the rest of the world. The Los Angeles Film Critics Assn. voted best-picture awards to “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” “Rocky,” “Kramer vs. Kramer,” “Terms of Endearment,” “Amadeus” and “Schindler’s List” — movies that also won Academy Awards and earned box office glory.

2019 Oscars: See the full list of nominees »

What changed? For one thing, many magazines and newspapers have either disappeared or downsized their film critic staffs in the last couple decades. There are fewer popular forums where critics have a chance to proclaim their favorites. Many critics have gravitated to the fringes of the internet, websites that pride themselves on their anti-populist credentials. And some of the mainstream critics who endure have joined the crusade against feel-good entertainment.

As it happens, my favorite movies of 2018 are mainly the same ones acclaimed by other critics — “Roma,” anointed by most critics’ groups around the country; “The Rider,” named best picture of the year by the National Society of Film Critics; and the highly praised foreign films “Shoplifters” and “Burning.” But I also give high marks to movies despised or derided by many other critics.

These maligned pictures matter first of all because they address social issues that seem especially important in divisive times. “Green Book,” for example, would deserve plaudits simply for acknowledging the phenomenon identified in the title — a largely forgotten book that published a list of hotels and motels open to African Americans in the segregated South and in many other parts of the country. The film is set in 1962, nearly a decade after the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown vs. Board of Education, a cornerstone in the civil rights movement that helped establish the precedent that “separate-but-equal” education and other services were not equal. The filmmakers remind us that the country was still rife with humiliations for black travelers, even for cultivated jazz pianist Don Shirley, eloquently portrayed by Oscar winner Mahershala Ali, who has already won a SAG Award for his “Green Book” performance.

FULL COVERAGE: Countdown to the 2019 Oscars »

Beyond that, the friendship that develops between Shirley and his driver and bodyguard, Tony Vallelonga (Viggo Mortensen), is highly affecting. Since the film is told from Vallelonga’s point of view, with a screenplay cowritten by his son, it does not tell the complete story of this relationship. But it’s a bit unfair to expect a single movie to have the same depth as a comprehensive tome on the history of civil rights in this country.

The picture may not be subtle, but it’s expertly engineered. The final scene, when Shirley decides to celebrate Christmas with the Italian American family of Vallelonga, is irresistibly moving. And the acknowledgment of Shirley’s homosexuality, which does not faze the macho Vallelonga, adds another element of touching inclusiveness to this deft portrayal of people overcoming biases to find common ground.

This gay theme links the film to another critical punching bag, “Bohemian Rhapsody,” the story of Freddie Mercury and Queen. A smash hit isn’t necessarily a great movie, and this one definitely has its flaws, but many of the criticisms have been misplaced. One of the complaints is that the film downplays Freddie’s homosexuality and his death from AIDS complications.

Oscar predictions: Times critics pick who will and who should win this year »

It is true that the movie doesn’t have graphic sex scenes — it is rated PG-13 — but it is honest about the singer’s sexual orientation. In one key scene Mercury tries to tell his girlfriend that he is bisexual, and she responds bluntly, “Freddie, you’re gay.” And during the last part of the movie, he tracks down the man who captivated him during a brief meeting earlier in the film.

The movie does surrender to some biopic clichés. And the supporting characters — including Freddie’s immigrant parents and the other band members — are drawn too sketchily to make much of an impression. This is essentially a one-man show.

But Rami Malek goes all the way with his portrayal of Freddie; he transforms himself physically and emotionally. And the final Live Aid concert scene, featuring Queen’s irresistible anthem “We Are the Champions,” is a knockout — musically overpowering without losing focus on the character at the center of the action. It’s often true that a movie with a rousing ending can overcome many of the weaknesses that came before, and viewers definitely walk out of this film in a mood of exhilaration. Beyond that, however, “Bohemian Rhapsody” — like “Green Book” — celebrates tolerance and inclusiveness at a time when the country has been sinking in a morass of anger and prejudice.

That same embracing vision enriches another recent movie that is unlikely to be in the Oscars conversation when it is eligible next year: “The Upside.” For one thing, the film — a stepchild abandoned when the Weinstein Co. collapsed — opened in January, a dumping ground for pictures considered virtually unwatchable. As if confirming the studio’s distribution pattern, the movie got terrible reviews from most critics.

And yet it grabbed audiences, turning into a true underdog success story. “The Upside” is adapted from a French film, “The Intouchables,” the story of a wealthy quadriplegic and the black working man who becomes his caretaker and friend. The original also drew the ire of many critics, but it was one of the best-loved foreign films of recent decades.

Your Oscars ballot for all 24 categories — with tips from a pro »

Some remakes of foreign films don’t make sense when shoehorned into a completely different culture. But “The Upside” emphasizes the gulf between the haves and have nots in Trump’s America, underscoring the challenges that face people living in poverty today.

Beyond its sharp social criticism, the movie showcases excellent performances. Bryan Cranston and Nicole Kidman demonstrate their professional sheen, but it is Kevin Hart who electrifies. He finds the biting humor in the predicament of an outsider alternately flummoxed and appalled by a rich man’s world; this idea actually comes through more strongly in the American remake than in the French original. And Hart’s hard-edged performance allows us to care about the character without ever begging for sympathy.

By trashing these uplifting movies, critics are unwittingly adding to the sour tone of our national discourse. There may be some popular films that deserve critics’ scorn, but in these current cases, audiences got it right, and critics flunked the test.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.