Climate change ravaged America’s oil capital. Can it lead on clean energy?

This is the April 7, 2022, edition of Boiling Point, a weekly newsletter about climate change and the environment in California and the American West. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

As the pontoon boat carried me and a dozen other journalists down the murky green waters of Buffalo Bayou — a slow-moving stream that flows through Houston and eventually empties into the Gulf of Mexico — I thought I could hear a waterfall.

Turns out I was listening to the roar of cars passing overhead on Interstate 69.

Highway sounds quickly drowned out the boat’s captain, leaving me to reflect on this strange confluence of nature and humanity. Buffalo Bayou is surrounded by industrial facilities and urban sprawl, but we also saw herons, an alligator and even baby turtles crawling across a trash containment boom. Houston was founded in 1836 along this stream, where it meets up with White Oak Bayou and boats have a wide berth to turn around. Unlike other local waterways, most of Buffalo Bayou was never lined with concrete — in part because future president George H.W. Bush helped protect it when he served in Congress in the 1960s.

We were exploring the bayou on the last full day of the Society of Environmental Journalists’ annual conference. I was happy to be outside, even if this was no pristine wilderness. It was the world as it exists in 2022: irrevocably altered, but still worth saving.

“There’s only one Earth. God is not making another one,” said the boat’s captain, David Rivers from Buffalo Bayou Partnership.

On Monday, the day after I returned home to Los Angeles, the United Nations released its latest climate report, focused on what can still be done to keep global warming from reaching catastrophic levels. Reading about the report in the Washington Post, I was struck by this sentence from reporters Sarah Kaplan and Brady Dennis, summarizing a conclusion reached by scientists: “In waiting so long to take action, humanity has denied itself any chance of making the energy transition gradual or smooth.”

Let that sink in for a moment.

If we’d started phasing out fossil fuels decades ago, when scientists first sounded the alarm about carbon pollution, maybe we’d have an easy glide path toward a habitable planet today. But that’s not what happened, especially in the U.S. Fossil fuel companies launched climate science denial campaigns that upended American politics, with lasting consequences. Now we’re scrambling to slash pollution without causing power outages, sending energy costs skyrocketing or putting oil and gas workers out of jobs.

“In waiting so long to take action, humanity has denied itself any chance of making the energy transition gradual or smooth.” It’s a reality that we all must come to terms with — and it underpinned much of what I learned and saw in Houston.

The conference began with Rice University scientist Daniel Cohan noting that our hotel offered views of “one of the three worst [highway] interchanges in all of Texas” — validating my rashly formed opinion that Houston is not a pretty place, and reminding me of my colleague Liam Dillon’s coverage of freeway expansions in Houston, L.A. and elsewhere displacing people of color.

The next morning, I joined a group of environmental journalists at Houston Advanced Research Center, where scientists showed us around one of the most energy- and water-efficient buildings in the Lone Star State. The research center pays monthly water bills of just $30 on average, has no natural gas hookups and produces more electricity than it uses thanks to rooftop solar panels.

Later that day, some of us explored a long-shuttered and poorly maintained landfill in Sunnyside, a predominantly Black neighborhood. A developer is working to convert the landfill to a community solar farm, which would provide low-cost electricity to nearby homes — if the developer is able to secure a state permit, as well as financing for the $75-million, 52-megawatt project.

“We can take trash and turn it into gold,” said Efrem Jernigan, who grew up in Sunnyside and is involved with the project.

It’s a hopeful vision that came up again and again during the conference: Low-income communities of color continue to suffer the most from environmental degradation, but clean energy offers unprecedented opportunities for justice.

During the plenary session I moderated on Friday afternoon, for instance — full video here if you’re interested — Jamal Lewis, director of policy partnerships and equitable electrification at the advocacy group Rewiring America, said “enhanced incentives” are needed to help low-income families afford clean energy technologies such as electric heat pumps and electric induction stoves.

In addition to fighting climate change, those technologies could reduce energy bills, and indoor air pollution from gas stoves.

“I’m 28 years old. My parents’ furnace is older than I am,” Lewis said during the panel. “If they were to transition and buy a new [gas] furnace, we’re basically locking in 30-plus years of fossil fuel investment. We can’t let that happen.”

Getting the right incentives to the right people is crucial — and so is speed.

During the same panel, Alex Breckel, director of clean energy infrastructure deployment at the nonprofit Clean Air Task Force, said the U.S. will need twice as much climate-friendly power as it has now by 2030, and three times as many miles of transmission lines by 2050. By the 2040s, he said, we’ll need to build as much solar and wind power every single year as we have on the grid today.

That’s a daunting task, but one that would bring enormous benefits if we pull it off.

Eliminating most combustion of coal, oil and gas would lead to dramatically cleaner air — and while marginalized communities would be the biggest beneficiaries, a new report from the World Health Organization found that 99% of the global population currently breathes poor-quality air, leading to millions of deaths each year. The faster we phase out fossil fuels, the faster the death count drops — and the faster the planet stops overheating, with marginalized communities again seeing the greatest benefits.

“Getting out ahead of the worst of climate change is an environmental justice policy,” Breckel said.

Can the U.S. and other countries actually build clean energy projects fast enough, given the political power of the fossil fuel industry and the inertia of the status quo? It’s an impossible question to answer, but Texas offers an intriguing case study. Cohan, the Rice professor, pointed out that Texas not only has more wind power than any other state, it installed more solar than California last year and previously built $7 billion worth of transmission lines while the rest of the country struggled to build any.

The Lone Star State’s clean energy successes have been fueled by its lax building regulations — especially compared to the Golden State’s, where some climate advocates say it’s far too difficult to build solar farms, wind turbines and affordable apartments.

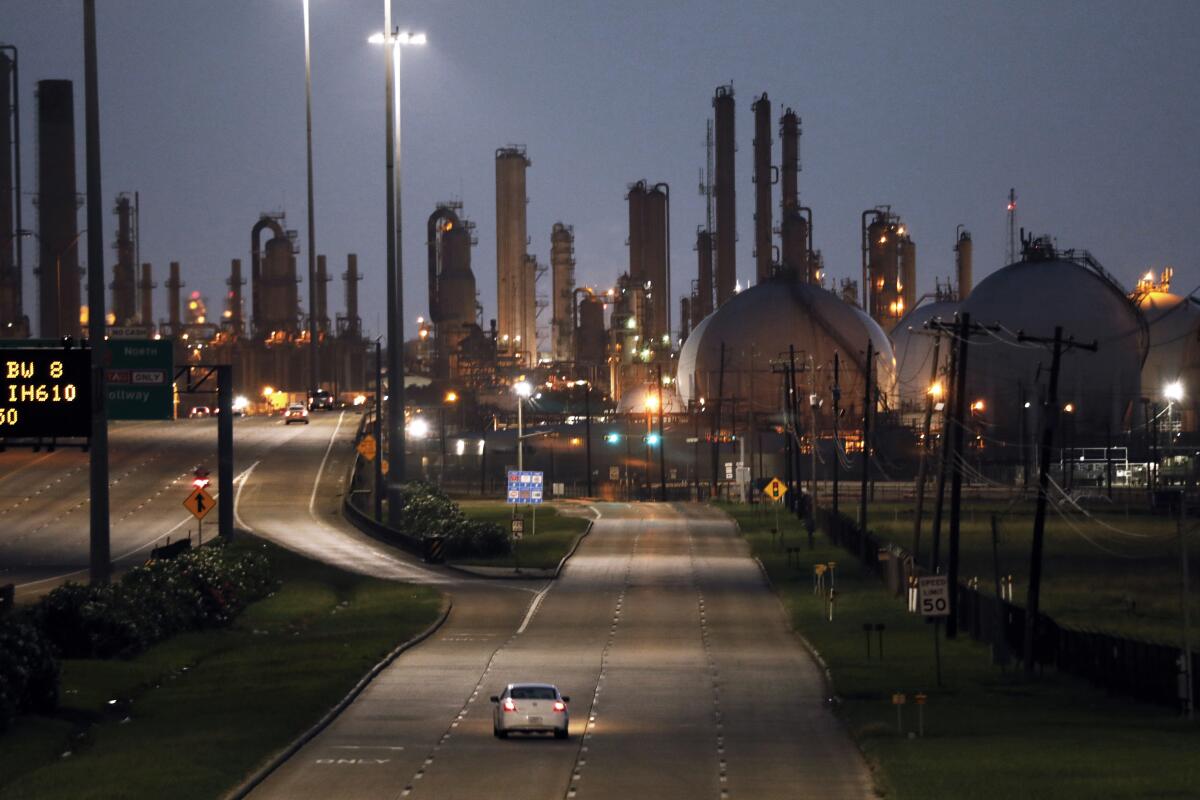

Houston is also the epicenter of America’s oil and gas industry — an industry that continues to drive the climate crisis even as it makes relatively small investments in carbon-capture technology and low-emission fuels such as hydrogen and biomethane.

Those technologies will probably be needed to clean up some industries — but can fossil fuel companies be trusted to wield them? Or are oil and gas firms simply using the promise of cleaner fuels and captured carbon to delay climate action?

That was the subject of another conference panel I joined on Saturday, moderated by Grist reporter Emily Pontecorvo. After I discussed my reporting on a hydrogen pipeline proposed by Southern California Gas Co., Emily asked investigative journalist Sara Sneath about her coverage of oil and gas companies using a Louisiana climate task force to promote carbon capture, and Time magazine’s Alejandro de la Garza about his recent story on a plan to bury carbon dioxide emitted by Iowa ethanol refineries.

Although there are climate arguments for all those plans, critics say they also reflect the fossil fuel industry’s unwillingness to simply stop polluting. For another example, see this piece by Nicholas Kusnetz at Inside Climate News, about how Occidental Petroleum wants to pull carbon out of the atmosphere — and use it to pull more oil from the ground in New Mexico and Texas.

“The people who created the problems may not be the best people to come up with solutions,” Robert Bullard, a professor at Texas Southern University known as the “father of environmental justice,” said during another conference session.

Again, the energy transition won’t be gradual or smooth. It will be disruptive and uncomfortable.

Of course, the climate crisis is also disruptive and uncomfortable — to put it mildly. The environmental journalism conference featured constant references to 2017’s Hurricane Harvey, which killed more than 80 people, knocked out power for hundreds of thousands of Texas homes and was likely made worse by global warming. There was also lots of discussion of last year’s Winter Storm Uri, which left millions of Texans without electricity for days as pipelines and power plants froze. Hundreds of people died.

It’s easy to hear about these kinds of tragedies and just shut down mentally, because solutions feel so far out of reach. To paraphrase one of my favorite authors, we live in a harum-scarum world, and sometimes doing the right thing feels impossible.

As I floated down Buffalo Bayou, though, the world seemed simple enough, at least for a few minutes. The waterway needed cleaning up, but Buffalo Bayou Partnership was working on that. They were building hiking and biking trails along the banks, too.

“I’ll be here fighting until y’all decide to catch on,” said Rivers, the pontoon boat captain.

Earth is getting hotter, deadlier and more chaotic. And yet solutions are still within reach. Keeping both those truths in mind — without succumbing to despair, or yielding to false optimism — may hold the key to navigating the bumpy ride ahead of us.

On that note, here’s what’s happening around the West:

TOP STORIES

California’s all-important April 1 water measurements showed Sierra Nevada snowpack at 38% of average — which is miserable, following so many dry years. As my colleague Ian James notes in his story on the pitiful snowpack, the state just finished its driest January through March on record, more than negating the water windfall from that big December storm. Worsening drought doesn’t seem to be inspiring much conservation, though; statewide, residential water use was at one of its highest levels in nearly a decade for the month of February, Ian reports. And oh yeah, the Sierra snowpack is already down to 31% of average.

A $2.6-billion deal between Gov. Gavin Newsom’s administration and major water agencies is meant to restore the West Coast’s largest estuary — but environmentalists, who were left out of the negotiations, say it wouldn’t do nearly enough for endangered fish. Here’s the story, once again from Ian James, who writes about the government’s latest, greatest effort to restore the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta — which also happens to be the ailing heart of California’s water-delivery system.

Valley fever can’t be treated, often goes undiagnosed and can cause debilitating pain — and yes, climate change is making it more common. California case counts are up 800% since 2000 as rising temperatures drive greater swings between intense rain and prolonged drought, creating ideal conditions for the fungus that causes valley fever, The Times’ Hayley Smith reports. It’s just one of many escalating climate consequences, with California’s nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office releasing a new report this week highlighting many of the dramatic changes already underway, as detailed by Rachel Becker and Julie Cart for CalMatters.

THE ENERGY TRANSITION

With gasoline prices staying high, this could be a defining moment for Americans embracing electric cars — if it weren’t so hard to get one, due to computer chip shortages and bottlenecked supply chains. My colleagues Ronald D. White and Russ Mitchell wrote about the creative steps some people are taking to acquire new or used electric cars. In a similar story, Benjamin Storrow wrote for E&E News about the challenges California is facing trying to build loads of battery storage as quickly as possible, to help keep the lights on this summer. Supply-chain delays and rising prices for lithium and other commodities are to blame.

Sempra Energy — parent company of Southern California Gas Co. — might invest in an offshore wind project along the Central Coast. That would be a change of pace for the fossil fuel giant. But at the same time, the company developing the wind farm, TotalEnergies, might buy liquefied natural gas from an export terminal Sempra is planning to build in Baja California, Rob Nikolewski reports for the San Diego Union-Tribune. And speaking of wind power, NextEra — the country’s largest renewable power developer — agreed to pay $8 million in penalties after being charged with violating the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, Matthew Brown reports for the Associated Press. At least 150 eagles were killed at NextEra wind farms in eight states, including California.

I wrote last year about the hydropower industry and leading environmentalists striking a hard-fought deal to tear down old dams, while also adding hydropower generators at other dams to produce climate-friendly electricity. Now several Native American tribes and Indigenous groups, including the Skokomish Tribe and the Upper Skagit Indian Tribe in Washington state, have signed on to the compromise plan, the Wall Street Journal’s Jennifer Hiller writes. But while hydropower can serve as a climate solution, it also faces immense climate challenges. The Western drought is drying up a big piece of San Francisco’s energy supply as Hetch Hetchy Reservoir declines, Jessica Wolfrom reports for the San Francisco Examiner. And in the Upper Colorado River Basin, funding for fish recovery programs is in jeopardy as hydropower sales fall, per Chris Outcalt at the Colorado Sun.

AROUND THE WEST

A gold-mining company abruptly ended exploratory drilling on Conglomerate Mesa, a “desert island in the sky” near Death Valley, after federal officials requested a more thorough environmental analysis. Here’s the story from my colleague Louis Sahagún, who notes that conservationists want to see the mesa protected as a national monument. We’re definitely going to be talking a lot more about mining, though. President Biden last week invoked the Defense Production Act to spur domestic mining of lithium, nickel and other metals crucial to the clean energy transition, most of which the U.S. currently imports from overseas.

A crucial wetland for migrating birds on the Pacific Flyway in Oregon’s high desert is drying up as alfalfa farmers drain groundwater that feeds local springs — and state regulators aren’t even tracking how much water they’re withdrawing. I learned a lot from this investigation by Emily Cureton Cook at Oregon Public Broadcasting, which made me think about another shrinking stopover on the Pacific Flyway, Southern California’s Salton Sea. In other bird news, I also loved this story by The Times’ Jeff Bercovici about the avian soap opera unfolding atop a Berkeley bell tower. I’m not a birder and didn’t expect to be especially riveted by Jeff’s tale of two peregrine falcons, Annie and Grinnell, but he made me care — and then dropped a gut punch.

How did feral hogs come to overrun California and much of the rest of the country? Be sure to read the wild story by my colleague Susanne Rust. The short version is that the hogs are super smart, have no natural predators and breed like crazy. And if you’re looking for another gripping wildlife read, check out this powerful story by Hal Bernton at the Seattle Times, told in partnership with the Anchorage Daily News, about how climate change is wreaking havoc on the Bering Sea snow crab harvest.

POLITICAL CLIMATE

Congressional Democrats castigated the leaders of major oil companies at a hearing Wednesday, blaming them for playing a role in high gasoline prices by refusing to increase drilling. But while BP, Chevron, Exxon Mobil and Shell seem to have some responsibility for the current oil supply/demand imbalance, the full picture is more complex, The Times’ Don Lee writes. In related news, President Biden wants Congress to force fossil fuel companies to start producing more oil on federal lands, or else give up leases they’re not using — and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi is open to making it happen, George Cahlink reports for E&E News.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service took the rare step of giving emergency Endangered Species Act protections to the Dixie Valley toad in Nevada, possibly spelling trouble for an under-construction geothermal power plant. Details here from Jeniffer Solis at the Nevada Current; this is only the latest example of a growing tension between renewable energy development and habitat conservation in the American West. In other regulatory news, the federal government will require emergency shutoff valves on oil and gas pipelines, more than a decade after a deadly explosion in San Bruno, Calif. — but only on new pipelines, meaning the requirement wouldn’t have prevented the San Bruno disaster, Matthew Brown writes for the Associated Press.

The Supreme Court’s five most conservative justices reinstated a Trump-era rule making it easier to build energy projects that can pollute waterways. Chief Justice John Roberts, a George W. Bush appointee, joined with the three liberals in slamming the decision, Kelsey Reichmann reports for Courthouse News Service. In other legal drama, an appeals court ruled that federal officials failed to fully evaluate the climate impacts of a Montana coal-mine expansion, per Matthew Brown at the Associated Press.

ONE MORE THING

As a general rule, you should be skeptical of anyone trying to convince you that actually, fossil fuels are good and we ought to burn more of them — people like Alex Epstein, author of “The Moral Case for Fossil Fuels.” Epstein has become highly influential in conservative circles by arguing that poor nations should fuel economic growth and improve living standards by doubling down on coal, oil and gas — an argument that might make sense except for the tiny matters of climate change and deadly air pollution.

But does Epstein really care about developing countries, or is he just shilling for fossil fuels? I can’t answer that question. But I can point you to this story by the Washington Post’s Maxine Joselow, which Epstein preemptively labeled a “slanderous hit-piece.” It focuses on newly resurfaced articles he wrote in 1999 while in college, in which he denigrated non-Western cultures as inferior.

“Their only academic merit lies in contrasting them to Western civilization as models of inferiority,” he wrote.

Something to keep in mind the next time a U.S. senator cites Epstein’s work — which, yes, has actually happened.

We’ll be back in your inbox next week. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please consider forwarding it to your friends and colleagues.