Canaries in the climate-change coal mine

This is the Oct. 20, 2022, edition of Boiling Point, a weekly newsletter about climate change and the environment in California and the American West. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

I’m Corinne Purtill, a science and medicine reporter here at The Times, filling in this week for my colleague Sammy Roth.

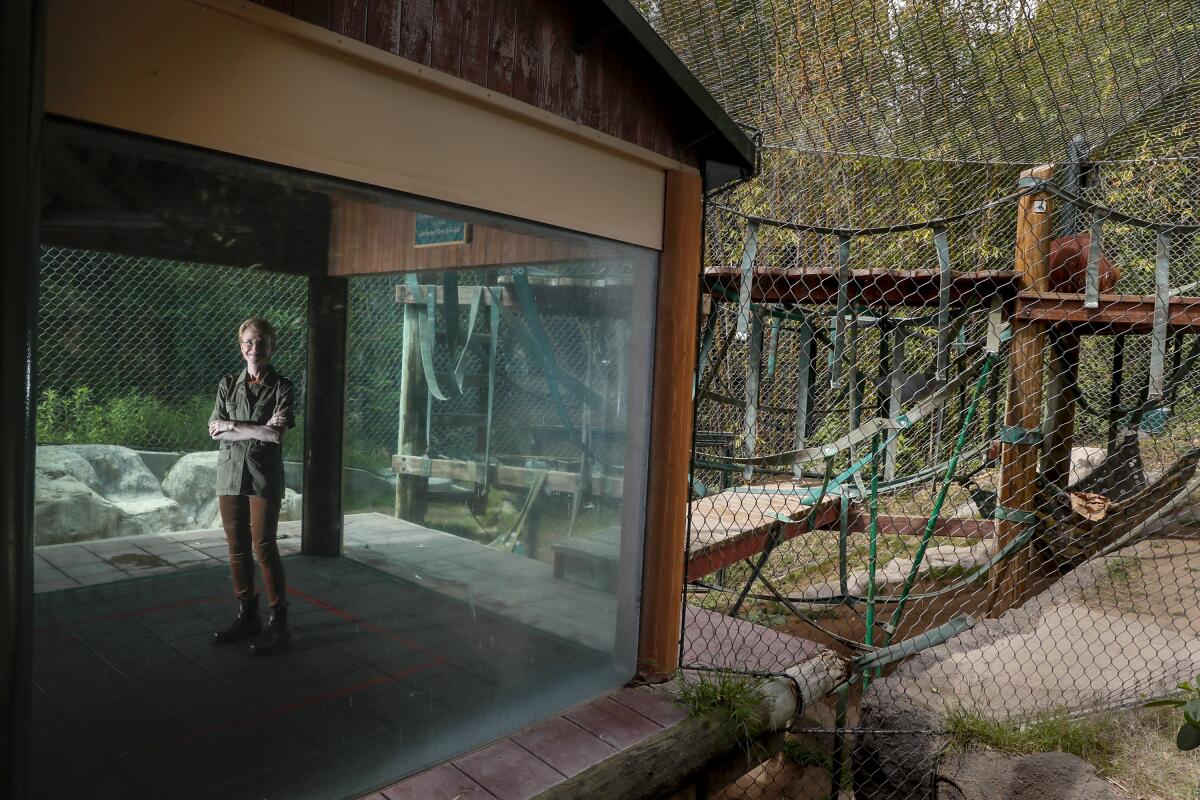

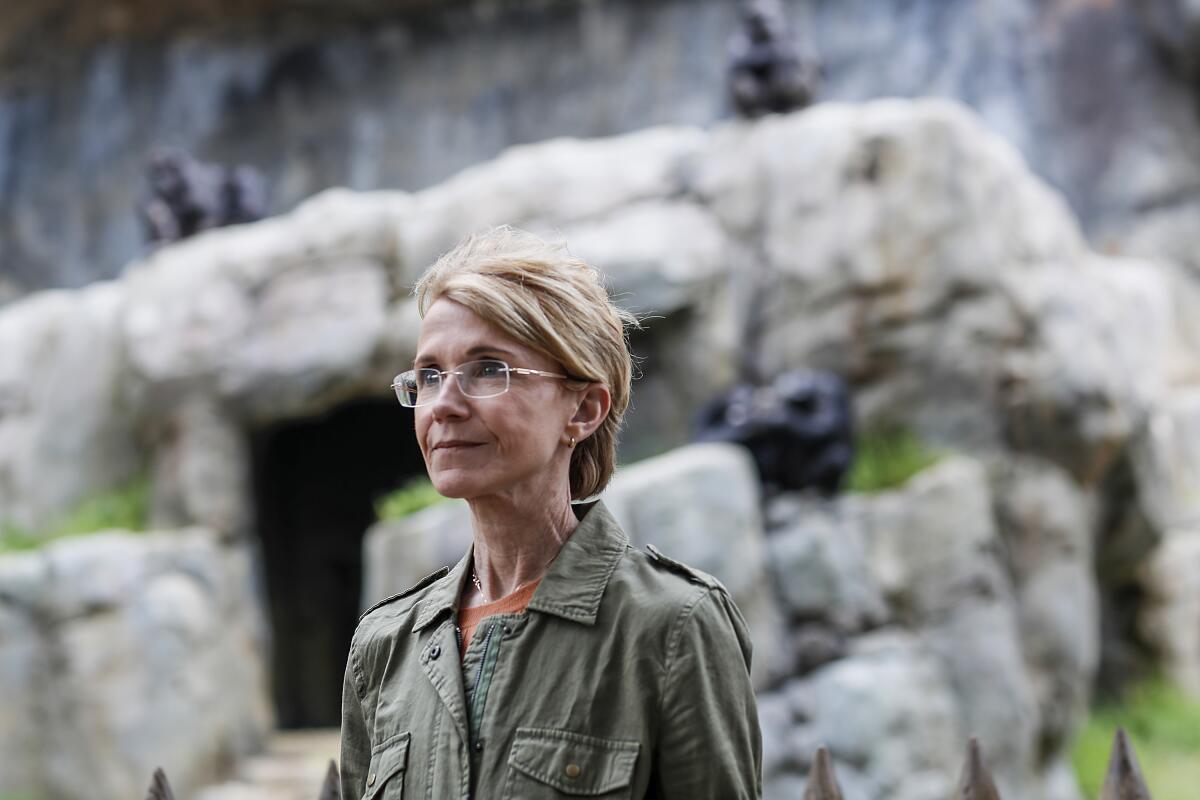

Not long ago, I interviewed Barbara Natterson-Horowitz, a UCLA cardiologist with one of her profession’s more interesting caseloads.

Some years back, Natterson-Horowitz was called to the Los Angeles Zoo to perform a transesophageal echocardiogram, a type of internal ultrasound she specializes in. She’d performed the procedure countless times but never in a case quite like this one. That day, she would treat a chimpanzee, her first non-human patient.

Working across species was a new experience for Natterson-Horowitz but not for the veterinarians who called her. Veterinarians read and study widely across the animal kingdom searching for solutions for their patients, who can’t verbalize the source of their pain or describe their symptoms. (Some have joked that human physicians are just vets who only know how to treat a single species, as Natterson-Horowitz and collaborator Kathryn Bowers wrote in “Zoobiquity,” their 2012 bestseller.)

When one of their primates got sick, it was a natural decision for the zoo’s veterinarians to call an expert in primate cardiology. So what if she happened to specialize in one of the order’s slightly less hairy species?

For Natterson-Horowitz, who studied evolutionary biology at Harvard under famed biologists E.O. Wilson and Stephen Jay Gould, the experience was life-changing. Seeing firsthand the similarities between our species and another’s, she told me, was like “that gleam of light you see when you crack open a door.”

She began researching health connections across species, and realized that in narrowly focusing on humans alone, physicians were missing out on a trove of valuable insights. Many of the species that share our planet are exposed to similar stressors and environmental contaminants. Some endure the same chronic diseases that humans do, while others appear to be naturally resistant.

That was especially true as she turned her attention to cross-species similarities in female health, the subject of her most recent work. Human women’s health is a field long underfunded, understudied and misunderstood. Diseases that primarily affect women get a disproportionately small amount of research money relative to the years of healthy life they steal. For many years, women were either underrepresented in clinical studies or omitted altogether.

The issue of biases and disparities is particularly relevant when it comes to environmental health and the profound changes facing all inhabitants of a rapidly warming planet. Climate change disproportionately affects the most vulnerable, both at the level of the individual organism and on the scale of nations. People with disabilities are routinely left out of climate change planning, a recent report from the Disability-Inclusive Climate Action Research Program at McGill University and the International Disability Alliance found. Across California and elsewhere in the world, communities of color are more likely to live in areas subject to extreme heat.

And because roughly 70% of the 1.3 billion people living in poverty worldwide are female, the United Nations has identified women and girls as uniquely vulnerable to the harm wrought by climate change. As Vice President Kamala Harris pointed out this week, there are parallels between how governments care for their most vulnerable and how willing they are to face the realities of a changing climate.

We are not the only living things being forced to learn to adapt on this planet. This year’s report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change found that warming temperatures had contributed to hundreds of local species losses, and accelerated the pace of extinctions. About half the species that have been assessed worldwide have shifted toward the poles or to higher elevations, my colleague Ian James reported.

And this gets to the heart of what Natterson-Horowitz is trying to tell her fellow physicians: The ways that our non-human planetary neighbors adapt may offer clues (or warnings) for us.

I spoke with Natterson-Horowitz for Boiling Point about climate change, gender and what we owe our fellow animals. Our conversation has been lightly edited.

There’s a striking line in your most recent paper: “In the 21st century, all female animals — including every human female — have become canaries and the Earth, a shared, planetary coal mine.” Can you talk a bit more about what this means at this particular moment in the environment?

Anthropogenic effects — climate, habitat destruction, ecological degradation — are blurring and, in some cases, erasing the lines that once demarcated human and animal environments. What this means is that many species are for the first time exposed to the same environmental factors as each other. When members of one species develop a pathology linked to an environmental effect, it should sound an alarm that other species may soon be impacted. In this context, the health of other species living in and around human populations should be watched closely. Essentially, it’s a modern conceptualization of the old “canary in the coal mine” practice, where animal disease helped keep humans healthy.

We know that climate change disproportionately affects the most vulnerable. Are there any examples of this in the animal kingdom, from a sex and gender perspective?

Temperature change on oocyte [egg cell] health and fertility is an example of sex-specific effect. Also, in many invertebrate and some vertebrate species, sex determination is thermally determined. Temperature changes are therefore changing sex ratios in some species.

But none of these exist in a vacuum. It is now widely understood that the adverse health impacts of numerous anthropogenic environmental changes are interconnected — in other words, climate change affects ecological contamination, and vice versa. Even though something like endocrine-disrupting chemicals are not directly related to temperature per se, I still believe they are relevant to a discussion about climate change.

There’s a wonderful new paper from Vicki Marlatt at Simon Fraser University that looks specifically at endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) in the environment and their effects on both female and male health in wildlife and humans. The uniquely female risks for mammals include cancer and congenital syndromes. One interesting highlight is that EDCs reduce fertility and increase uterine abnormalities in female sea otters and gray seals. When chemical exposure levels were reduced, fertility improved.

These chemicals bind to estrogen receptors, and they are highly lipophilic — that is, they accumulate in fat. Female mammals have a higher percentage of body fat mass than males, and therefore accumulate higher concentrations of these contaminants over their lifetimes. As I discuss in my own paper, this both disproportionately exposes females to carcinogenic and other disease-promoting agents, and endangers any offspring they have. Because environmental exposures during pregnancy can affect adult and even intergenerational health vulnerabilities, females’ reproductive health often plays a central role in shaping a species’ overall health and stability.

Are there any examples of non-human animals that seem particularly well suited to surviving climate fluxes in ways that might be instructive for humans?

I have been interested for a long time in animals with evolved adaptations that confer resistance to environmental challenges. There are many fabulously interesting such species. For example, many fish in the Arctic and Antarctic produce freezing point depression glycoprotein in their blood — essentially, they make their own antifreeze. Now there is growing interest in identifying adaptations of relevance to climate change.

I have been working with Peter Stenvinkel of the Karolinska Institute in Sweden and others to identify animals with resistance to modern lifestyles and climate-related effects. Stenvinkel has a paper that presents some fascinating examples of animals with climate-related adaptations. One of the most colorful examples is heat-shock protein in dromedary camels, which play a role in homeostasis and heat tolerance. Camels haven’t just adapted physiologically to extreme heat and drought — they have adapted on the molecular level.

You’ve written a lot about what animal health can do for humans. What responsibility does human medicine have to non-human creatures?

This cuts both ways. The emergence of environmentally linked diseases in humans can and should be used to enact preventive measures to protect non-human animals who are similarly exposed. I believe human health professionals should develop an expanded sense of responsibility, and knowledge of human environmental risk should be communicated to veterinary professionals. Knowledge gained should be used to benefit all animals — not just us.

On that note, here’s what else is happening around the West:

TOP STORIES

2020’s fire season set us back even further than we realized. Between 2003 and 2019, California’s efforts to limit greenhouse gas emissions led to a 13% reduction in emissions, preventing 65 million metric tons of pollution from reaching the environment. The 2020 fire season, the worst in state history, sent double that amount of pollutants spewing into the atmosphere. “Essentially, the positive impact of all that hard work over almost two decades is at risk of being swept aside by the smoke produced in a single year of record-breaking wildfires,” Dr. Michael Jerrett, a UCLA professor of environmental health sciences and a lead author of a new study that quantifies the cost of wildfires in dollars ($7.1 billion in damages globally) and greenhouse gas emissions.

California will become the first state to require insurers to give premium discounts to home and business owners who take steps to guard their property from wildfire. The Department of Insurance announced Monday that it would reward consumers who take wildfire safety and mitigation measures outlined in the state’s Safer From Wildfires framework. As the intensity and frequency of wildfires has increased in recent years, ratepayers have complained that companies have been unwilling to credit them for efforts to lower the risk of loss and damage, such as clearing combustible vegetation from properties or installing fire-resistant roofs, Times reporter Hayley Smith writes.

Last year’s shipping logjam was unhealthy for local residents. As Janet Schaaf-Gunter watched gray exhaust settled over San Pedro Bay last year, she worried about how much diesel pollution she and her neighbors were inhaling during the shipping logjam at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. Her worries were confirmed recently when port officials announced an unprecedented increase in harmful emissions. In addition to spiking air toxins at both ports, greenhouse gas emissions were up 39% in 2021 at the Port of L.A. and 35% at the Port of Long Beach. As Times environmental writer Tony Briscoe reports, the news has outraged neighborhood activists and clean air advocates, who say the ports are failing on promises to mitigate their effects on air quality.

POLITICAL CLIMATE

As elections near, L.A.’s water supply becomes more urgent than ever. Hayley Smith recently took to the sky with L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti to review the state of the city’s water supply, gazing down at the Hollywood Reservoir from 1,200 feet. Water independence is vital for the city’s 4 million residents and for the county and region as a whole. Imported supplies from the State Water Project are heavily dependent on annual snowpack and rainfall in the Sierra, which are no longer guaranteed under the state’s shifting climate. And federal supplies from the Colorado River are rapidly drying up, with the river’s largest reservoir, Lake Mead, nearing dangerously low levels. But Garcetti said neither of the two candidates seeking to replace him had reached out to discuss the city’s water goals. (In emails to The Times, both Rep. Karen Bass and Rick Caruso said they believed Los Angeles must reduce its reliance on imported water.)

The Clean Water Act needs refurbishing. The U.S. Clean Water Act of 1972 was closely modeled on California’s Porter-Cologne Water Quality Control Act. Both laws regulate pollution to ensure the nation’s water supply remains safe and healthy for the humans and other life forms that depend on it. But a case currently before the U.S. Supreme Court could jeopardize the federal act, argues the Los Angeles Times editorial board, at least to the extent that it protects sensitive wetlands. The board believes that even if the court accepts the broader view of the Clean Water Act’s scope, the 50-year-old law should now be only a starting point for further protections of the nation’s water. Half-century-old water laws must be updated to take into account climate change, agricultural runoff and our deeper knowledge of the actual connections among all bodies of water, whether on the surface or underground, seasonal or year-round.

AROUND THE WEST

Western wildfires are fueling foul weather elsewhere. We’re getting uncomfortably accustomed to seeing fires big enough to create their own weather. It turns out that fire may be capable of influencing things much farther afield. A new study from the U.S. Department of Energy finds that the growing intensity of wildfires in the West are contributing to extreme hail, intense rainstorms and flash floods in states including Colorado, Wyoming, Oklahoma and Nebraska. Intense heat from the fires can shift air pressure in the atmosphere, researchers found, which creates strong eastern winds carrying smoke particulates and more atmospheric moisture. When those winds reach storms already brewing a few states away, it can make them even stronger.

A giant donation from farming moguls will fund a new center for agricultural studies. UC Davis will build a $40-million agricultural resource center focused on improving crop sustainability and resiliency, water and energy efficiency and expanding access to nutritious food. The 40,000-square-foot building will be known as the Lynda and Stewart Resnick Center for Agricultural Innovation, after the Beverly Hills billionaires who donated $50 million for the center. The Resnicks run one of the country’s largest farming empires, with their company, the Wonderful Co., selling popular supermarket items like Halos mandarin oranges, Pom Wonderful pomegranate juice and Fiji Water. Salvador Hernandez has the story.

What’s killing the Pacific’s gray whales? When large numbers of emaciated gray whale carcasses began washing ashore on North America’s Pacific coast in 2019, many scientists hoped it was just a short-term phenomenon. Three years later, however, the whales’ population is down 40% from their 2016 peak, and a recent NOAA report found that the number of calves born last year was the lowest since the agency started keeping track in 1994. Scientists believe multiple interwoven factors are to blame: warming temperatures, a loss of sea ice and climate-related changes to the habits of the whales’ prey, as my colleague Susanne Rust reports. Sadly, gray whales aren’t the only cetacean losses in the Pacific: Last week, nearly 500 pilot whales fatally beached themselves on New Zealand’s Chatham Islands.

THE ENERGY TRANSITION

On Dec. 6, the U.S. will hold its first-ever lease sale for offshore wind energy on the West Coast, the Biden administration announced Tuesday. Targeted on the Pacific Ocean off Central and Northern California, the auction will be the nation’s first for commercial-scale floating offshore wind energy development. Wind energy in the Pacific is a major component of the Biden administration’s green energy goals. U.S. Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm told reporters in a call last month that floating offshore wind turbines could eventually produce up to 2.8 terawatts of clean energy. Gov. Newsom applauded the move, with the state calling it a “historic step” toward California’s goal of 90% clean energy by 2035.

The World Bank veers. In December 2018, the World Bank publicly committed to aligning its spending more closely with the goals of the 2015 Paris climate accord. But as Jessie Blaeser reports in Grist, reality has swerved far from that ideal. Since making its public promise, the World Bank Group has given nearly $15 billion in financing to 144 fossil fuel projects and policies, according to a new report from the Big Shift Global, a nonprofit campaign for energy transparency. The group’s analysis of public data from Oil Change International’s Public Finance for Energy database found that many of the new projects are in countries already grappling with the most serious consequences of climate change.

A desalination plant gets the OK. Less than six months after rejecting a major proposed desalination plant in Huntington Beach, the California Coastal Commission unanimously approved a smaller Orange County site that could serve as a model for future plants that convert seawater to drinking water. The Doheny Ocean Desalination Project near Pacific Coast Highway and San Juan Creek in Dana Point will be operated by the South Coast Water District, which serves about 40,000 residents and 2 million visitors annually. When completed in 2027, the plant will be able to produce up to 5 million gallons of potable water per day, enough to slash the district’s reliance on imported water from 90% to “anywhere from 20% to 40%,” said Rick Shintaku, the district’s general manager. But desalination is not without controversy, The Times’ Hayley Smith reports, and the commission’s approval came with more than a dozen conditions that the water district must meet.

ONE MORE THING

Fat Bear Week, which concluded Oct. 11 at Alaska’s Katmai National Park and Preserve, is not just about the bears. It’s not about the salmon, either, of which the bears eat up to 500 pounds per week in an effort to bulk up in advance of their winter hibernation.

No. Fat Bear Week, according to the park’s official website, is “a celebration of success and survival,” a testament to the “resilience, adaptability and strength of Katmai’s brown bears.” In a world increasingly inhospitable to charismatic megafauna, Fat Bear Week — in which viewers of Katmai’s live riverside bear cams cast their votes for their favorite rotund ursine — is a tribute to bears’ right to live as bears should: free, fat and full of salmon.

Congratulations to this year’s winner, two-time champion Bear 747, weighing in at an estimated 1,400 pounds.

We’ll be back in your inbox next week. If you enjoyed this newsletter, or previous ones, please consider forwarding it to your friends and colleagues. On Twitter, follow @corinnepurtiill for news on science and medicine and @Sammy_Roth for climate and environment news.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.