Coronavirus shutdowns are lowering greenhouse gas emissions; history shows they’ll roar back

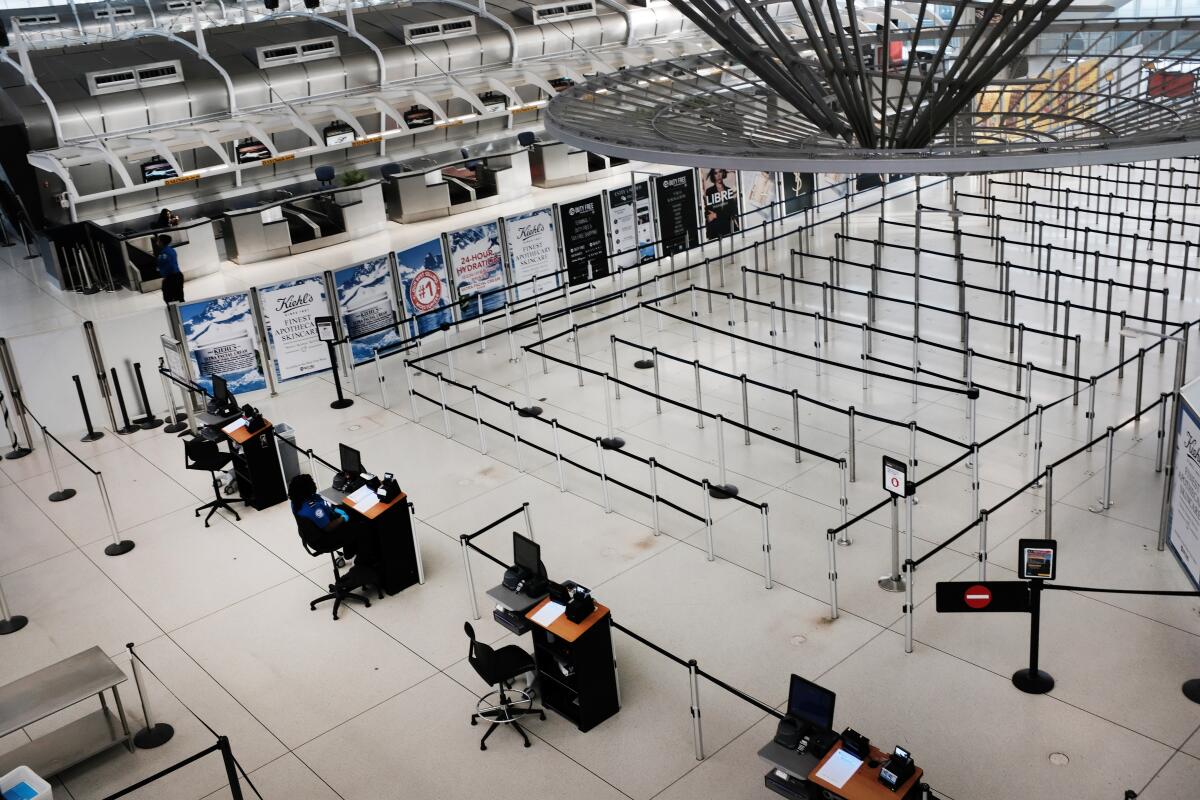

The global struggle to slow the spread of the coronavirus has brought with it canceled flights, closed businesses and a quickly escalating economic slowdown that could be devastating to millions. It is also certain to shrink greenhouse gas emissions this year, according to climate scientists.

But does that mean we are turning a corner in cutting planet-warming pollution?

If history is any indication, no. The slide in emissions will be temporary, experts say. What’s more, scientists and environmentalists worry the pandemic will at the same time undermine government and industry’s resolve to cut emissions in the long term.

Experts are predicting the health crisis will cause global emissions to drop for the first time since 2009, during the Great Recession. But a look back over the decades shows a steady rise in greenhouse gases punctuated by temporary dips caused by economic downturns, including the 2008 global financial crisis and the oil shocks of the 1970s. Pollution bounces back predictably once the economy starts improving again, with the resurgence in industrial activity, travel and consumption more than offsetting any short-lived benefits to the climate.

“I won’t be celebrating if emissions go down a percent or two because of the coronavirus,” said Rob Jackson, an environmental scientist at Stanford University who chairs the Global Carbon Project. “We need sustained declines. Not an anomalous year below average.”

Global greenhouse gas emissions rose only slightly in 2019, Jackson said, so it wouldn’t take a big economic shock to push them downward.

NASA and European Space Agency satellites have detected big drops in air pollution concentrations in China and Italy as millions went under lockdown or quarantine to slow the virus.

At the same time, there are already some indications industry and regulators want to put the brakes on climate action. Airlines that only months ago were touting efforts to go carbon-neutral to address their rapidly rising emissions are now hit so hard by the slowdown they are warning they will run out of cash without billions in government aid. In Europe, now the epicenter of the pandemic, some airline companies have pushed regulators to delay emissions-cutting policies on account of the coronavirus. The Czech Republic’s prime minister urged the European Union to abandon a landmark law seeking net zero carbon emissions to focus instead on battling the outbreak.

“I’m concerned about a sustained downturn in the economy and the narrative that we no longer have the luxury of addressing emissions,” Jackson said. “That would be devastating.”

Los Angeles and Long Beach officials, meanwhile, cited the virus-related hit to cargo volumes at the nation’s largest seaport as one reason for voting to approve only a modest clean-air fee on shipping containers earlier this month. Air quality officials said the $20-per-container fee is too low to make adequate progress cutting greenhouse gas emissions from thousands of diesel trucks that move goods through a complex that comprises Southern California’s largest single source of air pollution.

Alex Comisar, a spokesman for L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti, said the city-owned port is “not backing down on our environmental goals.”

“Tariffs have a very real impact on our port, and COVID-19 does add another level of uncertainty that we are already beginning to feel,” Comisar said, adding that officials will revisit the fee annually “to closely monitor its economic and environmental impacts, and ensure no ground is lost in the fight against climate change.”

Some environmentalists are optimistic that social distancing measures being adopted to slow the coronavirus, including a sudden shift to working from home and drastic reductions in air travel, could permanently change people’s attitudes about the transformations needed to slow climate change.

Well before the virus emerged, there was a growing “fight-shaming” movement and a trend among environmentalists and scientists to reduce their carbon footprint by forgoing travel in favor of virtual meetings and videoconferencing.

Martha Dina Argüello, executive director of the environmental health and justice group Physicians for Social Responsibility - Los Angeles, said the coronavirus accelerated discussions she and her staff were already having about cutting back on travel to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. On Thursday, the group’s 11 staff members began working remotely, quickly shifting to Zoom and other online meeting and communications platforms.

“I’m a boomer and I’m learning how to use Slack,” she said. “We will learn that some habits we can change. But I worry that while my individual footprint is one thing, the practices of the oil industry are another. Will they get out of the way of us doing better climate policies?”

“If our national response is to worry more about the economic impacts and buttress the stock market and industry, then it doesn’t bode well,” she added.

There is precedent for environmental concerns being pushed aside during times of crisis, only to be followed by a resurgence in pollution as the economy recovers, as was the case after the 2008 global financial crisis.

“After a decrease, you saw carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuel and cement bounce back in a major, major way in 2010,” said Kelly Levin, a senior associate in the climate program at the World Resources Institute, who worries about the world following a similar trajectory as leaders take urgent, short-term measures to stimulate the economy.

“I think there’s a huge risk that we could boost activity in traditionally heavy industries,” Levin said, though it doesn’t have to be that way. “We know that economic interventions, even short-term ones, that are low-carbon can create more jobs and higher productivity. And that’s certainly what we’re going to need.”

Economic downturns sometimes push in both directions simultaneously, with businesses and governments responding with some economy-boosting measures that hurt the environment and others that promote conservation.

That’s what happened with the oil crises of the 1970s.

“It drove everything from fuel efficiency gains to Alaskan oil production. It transformed our economy,” Jackson said. “But the savings and loan crisis of the 1980s and ‘90s and the housing crisis of 2008 pushed us the other way. Housing and banks were in trouble. So companies spent less on the environment.”

The world’s inability to coordinate a response to the coronavirus pandemic also draws clear parallels with international efforts that have repeatedly failed to respond to climate science showing irreversible impacts if global average temperatures rise more than 2 degrees Celsius. The setbacks have grown considerably in recent years as President Trump and other world leaders abandon emissions reduction pledges in favor of fossil fuel-friendly policies.

“It may provide an object lesson in what happens when you don’t cooperate with other countries,” climate activist and 350.org founder Bill McKibben said of the coronavirus, in an email. “A wall can’t keep out the COVID microbe, any more than it can knock down a CO2 molecule.”

Climate change, after all, will continue to threaten to humanity long after COVID-19 fades.

A 2018 climate assessment by federal agencies found that if greenhouse gas emissions continue to climb, economic losses will be in the hundreds of billions annually in some sectors by the end of the century. The report also projects 9,000 Americans will die early each year by century’s end due to extreme heat from climate change if emissions continue to rise.

It will be much worse in poor countries. Researchers predict that India could see more than 1 million heat-related deaths a year by 2100 if temperatures rise 4 degrees Celsius.

“It would be unfortunate if we retreated from climate action for something that may be as short term as the coronavirus,” Jackson said. “There will be another coronavirus, there will be another recession, but climate change motors on. We have to deal with it through the ups and downs of the global economy. We have no choice.”