Screenings to help treat the right cancers

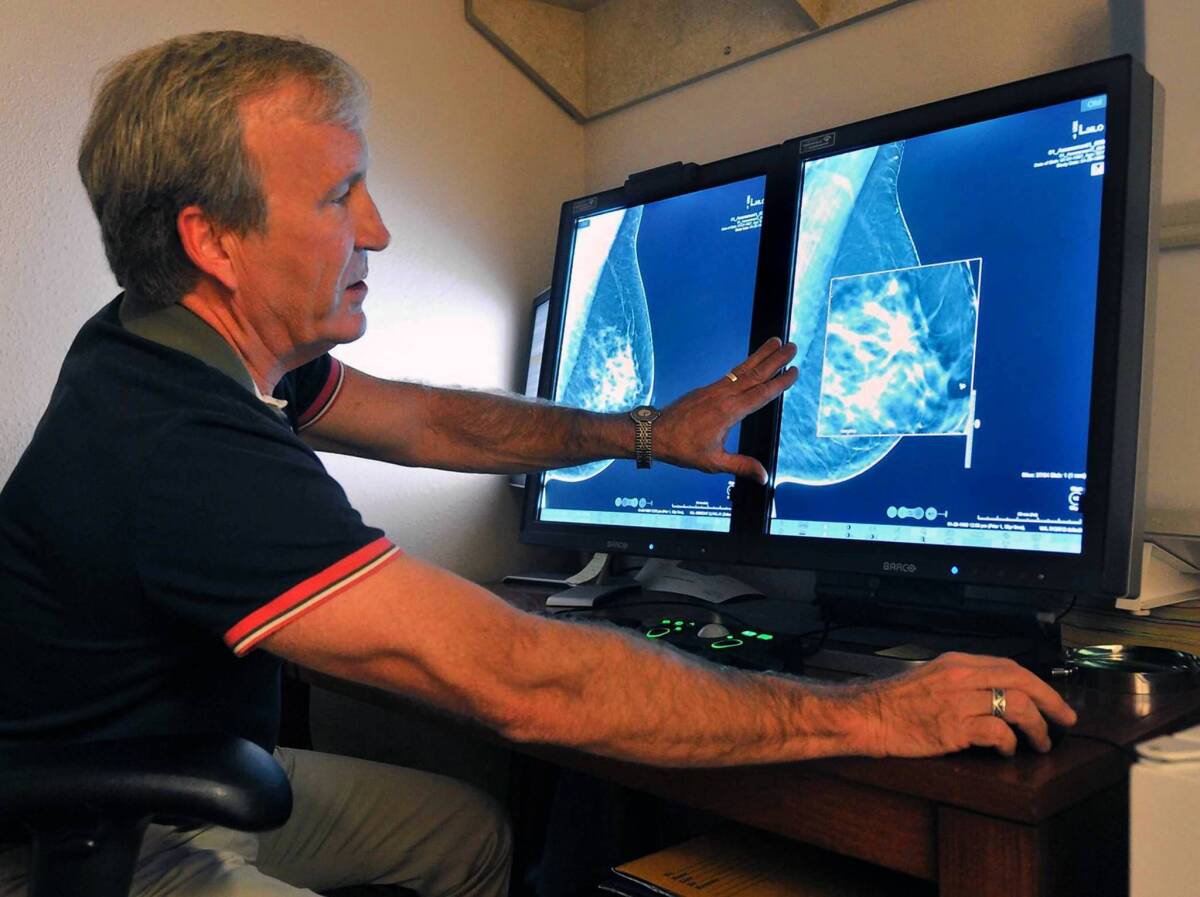

Cancer is running out of places to hide. A new blood test can ferret out a single cancer cell tucked away among a billion healthy cells. Radiologists are using crystal-clear 3-D mammograms to find suspicious spots and lumps that they never could have seen with an old X-ray machine. And CT scans can detect the earliest signs of lung cancer before a patient even has a chance to feel out of breath.

Today’s doctors have the tools and technology to catch all sorts of tumors that would have gone unnoticed in years past. The new advances in screening could lead to a huge upswing in cancer diagnoses and treatments in the near future. It seems like progress, but ever-more sensitive tests are also a recipe for trouble, says Dr. Gilbert Welch, a professor of Medicine at the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Research in Hanover, N.H.

“We’re getting good at finding cancers, but it would be better if we looked less hard,” Welch says. “We don’t need to find more cancers. We need to find the right cancers.”

Many cancers found through today’s screening tests are small, slow-growing and essentially harmless. But once cancer shows up in a blood test or a mammogram, it’s a good bet that treatment will soon follow. That often means surgery, chemotherapy or radiation, complete with all of the side effects and complications.

It’s hard to know how much patients really benefit from wide-scale screening. After decades of research, doctors are still debating the value of routine PSA blood tests for prostate cancer and mammograms for breast cancer. The tests may save some lives, Welch says, but they undoubtedly force far more people to cope with the aftermath of treatment they didn’t really need.

“It’s important for the general public to understand that it isn’t necessarily good for their health if we start looking even harder for cancer,” he says.

As doctors get better and better at finding cancers, they — and their patients — will need to seriously rethink the disease, says Dr. Barnett Kramer, director of the division of cancer prevention at the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Md.

They’ll also have to rethink their idea of a “cure.” In some cases, it might not be possible — or even a good idea — to rid a patient of every last cancer cell. And they’ll have to let go of the belief that all cancers need to be treated.

“Everyone carries around in their head the idea that cancer is a death sentence,” Kramer says.

In the future, doctors will increasingly face the key challenge of cancer: telling the difference between the tumors that could take a life and those that are just taking up space. On that point, the future looks bright. Researchers are gaining a clearer understanding of tumors and how they behave, raising the hopes that screening tests will do a better job of honing in on the cancers that really matter.

“If we learn more and more about the natural history of tumors, that will lead to better treatments, better screening strategies and better advice to patients,” Kramer says.

That work is taking place all over the country, including the lab of Dr. Joshua LaBaer, the chair of personalized medicine at Arizona State University in Tempe. “One of our main goals is to develop tests not only to detect cancers, but to determine if they are going to be a bad actor,” says LaBaer, who studies the genetics of tumors.

Like many other researchers, LaBaer is looking for “biomarkers” — such as antibodies or proteins — that could signal the presence of a dangerous cancer. So far, such cut-and-dried signs have been elusive. Instead of looking for single markers, doctors of the future may have to use complicated screening tests that pull together lots of pieces of genetic information combined with statistics and some well-informed guesses, he says.

“We’re going to have to use our heads,” LaBaer says.