More than 1 in 7 men have no close friends. The way we socialize boys is to blame

This story was originally published in Group Therapy, a weekly newsletter answering questions sent by readers about what’s been weighing on their hearts and minds. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

I’ve written quite a bit about disconnection in this space: the loneliness of being immunocompromised, the dearth of intergenerational relationships in Western culture, and why the need to belong is so human (and what can happen when we feel like we don’t).

What I haven’t acknowledged fully, though, is that how we relate to others is profoundly shaped by our social conditioning, or what we’re trained to think, believe, feel and want based on our various identities and where we live in the world. And so much of that conditioning hinges on gender. From the time we’re born, we receive explicit and unspoken messages from our families, our teachers, our religious institutions, the media and our peer groups about what it means to be a man or a woman.

Get Group Therapy

Life is stressful. Our weekly mental wellness newsletter can help.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

A reader sent us a question that touches on how gender socialization inevitably seeps into our relationships: “How is the epidemic of loneliness experienced by men? Are we doing enough to support men’s mental health?”

In today’s newsletter, we’ll look at the social forces that can make it harder for men to form deep, trusting friendships, how this reality affects men and their families, and what men and our culture as a whole can do to address this problem.

A quick note: As is always the case when we write about trends, I’ll be making some generalizations about how men are socialized and how they show up in relationships. There are always exceptions to dominant norms. There are also people who were socialized as girls but are nonbinary or trans men, and may not fit the typical profile of culturally prescribed masculinity. So, it’s complicated!

Why do men tend to have fewer close friendships?

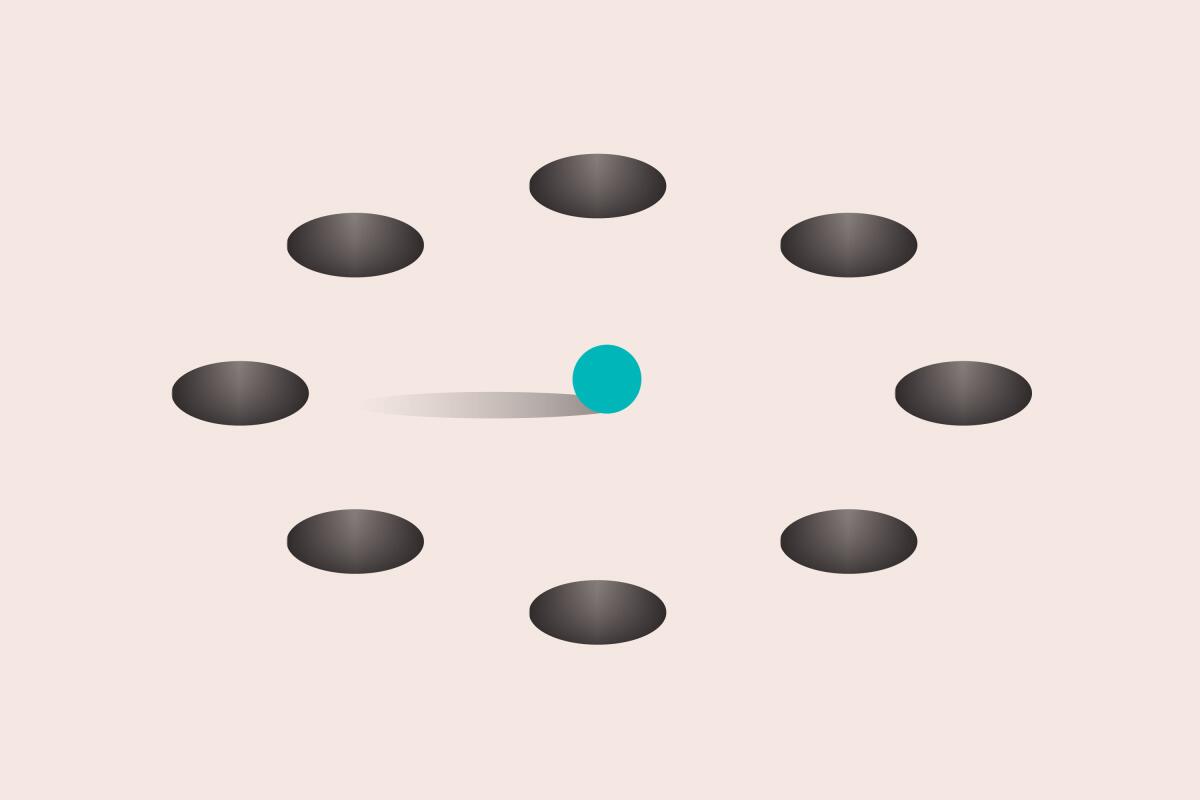

In a lonely world that keeps getting lonelier, men, on average, are the loneliest.

Thirty years ago, a majority of men (55%) reported having at least six close friends. Today, that number has been cut in half, according to survey data. And 15% of men reported having no close friendships at all, a fivefold increase since 1990.

A lot has been written about why this might be the case. There are larger forces at play here that affect people of all genders, like social media, erosion of local community institutions, and the pandemic. But the reason why men feel more alone, on average, has a lot do with what’s expected of them.

In the West, men are socialized to be strong and impervious to difficult emotions. They’re told from a young age to “be a man” or “man up,” and that they should be able to handle stressful life events on their own, said Elwood Watson, professor of history, Black studies and gender and sexuality studies at East Tennessee State University.

If I haven’t made it clear enough at this point, this fear of vulnerability among men isn’t inherent. It’s taught. Psychologist Niobe Way interviewed boys about their friendships in each year of high school, and found that younger boys spoke passionately about their affection for and reliance on their male friends. Research also shows that boys are just as likely as girls to disclose personal feelings to their same-sex friends and they are just as talented at being able to sense their friends’ emotional states, according to Lisa Wade, a sociology professor at Tulane University.

But by the time boys are in their teens, they’re conditioned to prize achievement and competition and to devalue intimate friendships with other boys, experts told me. Boys learn to not turn to their friends to talk about certain things, because they don’t want to be seen as weak or gay (“No homo”).

“A lot of boys and men are lonely because they’re ashamed of what they think and feel. Their peer group has basically said to them, ‘We don’t want to hear it,’ or ‘you’re a downer, you’re a bummer. Why don’t you just get it together?’ And so guys have gone silent,” said Fred Rabinowitz, psychology department chair at the University of Redlands and the author of “Deepening Group Psychotherapy With Men: Stories and Insights for the Journey.” “That silence creates more self-doubt, more angst.”

Guys learn to process emotions on their own, or turn to a female friend, a romantic partner or a sister, said Kevin Roy, professor of family science at the University of Maryland. “Over time, you lose the skills to maintain those relationships. And when you do have male friends, there’s only a few topics you can talk about: sports, work, women. Sharing about grief and loss and hard stuff is very difficult to do.”

The highest suicide rates are seen among single men in their 40s and 50s, and experts suspect that this trend is caused in great part by loneliness and the social expectations that help create loneliness. Research has suggested that unmarried women tend to be less lonely than unmarried men, because men are more likely to turn to their partners (and not their friends) to get the bulk of their emotional needs met.

This setup places the burden on men’s partners to be everything to them — their best friend, lover and caretaker, all rolled into one. Laughably, this tendency has been coined “emotional gold-digging.” “A lot of women say they wish their husbands had closer friendships,” Watson said. “And then when there’s divorce, men find themselves truly alone, which can result in more depression, stress and anger.”

So what can we do?

When asked about what they want from their friendships, men are just as likely as women to say that they desire emotional support and closeness.

But how might men go about finding true companionship with other men in a culture that, by and large, doesn’t endorse it?

The obvious answer is that men will need to become more self-aware. “Take time to look at your own behavior, look at where you feel comfortable and don’t, and lean into some of those hard situations,” Rabinowitz said. “Maybe you go out with these guys and you watch football at a bar, and you don’t tell them anything much about yourself. What if next time you asked a question like, ‘How is everyone doing at home?’ We need to have more modeling of being open.”

Because of social conditioning, it may take a lot of trial and error before you’ll find other men who can reciprocate emotionally, Rabinowitz said. They’re out there, for sure — but you might have to swallow a big dose of rejection before finding them.

Roy has experienced this firsthand. “It’s hard to bring stuff to other men, to assume they’ll get what I’m saying if I open up to them. You just have to push through that,” he said. “I’m experimenting almost little by little, bringing things to close friends, saying, ‘This is what’s going on.’ There’s a relief when people say, ‘Oh God, me too.’”

Whenever there’s a social problem this pervasive, we have a tendency to put the entire onus on the individual rather than looking at what we, and what our political leaders, can do. But it takes both collective and individual action to create change.

In this case, we all need to evaluate how we perceive and interact with masculinity — and many of us will need to redefine it, experts told me. And we need to allow boys and young men to explore the full range of who they are, what they feel and what they want in life, even if that doesn’t line up with stereotypical ideas of masculinity.

“When we encourage men to bring their feelings to the table, it’s scary for everyone, not just them,” Roy said. “When men step up and say, ‘I’m feeling this, I’m a mess,’ no one knows how to react, including women. We want to see this change, but there’s such a stigma when men actually try to show up differently.”

Roy said he feels encouraged by the growing conversation about male friendship. But he’s concerned that some men are offering solutions without challenging the privilege and power held by white men in particular.

“Yes, we should encourage men to confront their loneliness and sadness, but the answer isn’t doing the traditional guy thing, go into a sauna and beating drums and forgiving our ‘father wound’ [a favorite topic of men’s rights activists, who believe men are systematically disadvantaged because of their gender]. I see a lot of suggestions like that, which just maintains male privilege — you’ve improved yourself, and that’s it,” he said. “The bigger issue is what we do as a community, and the laws and policies we enact. These are tough questions.”

Gen Z, on the whole, takes a much more expansive view on masculinity and mental health. Roy sees this in his own kids. But he also sees the Andrew Tates of the world. “It goes in both directions. This is going to be a very long haul,” Roy said. “Any big change will take generations.”

Until next week,

Laura

If what you learned today from these experts spoke to you or you’d like to tell us about your own experiences, please email us and let us know if it is OK to share your thoughts with the larger Group Therapy community. The email GroupTherapy@latimes.com gets right to our team.

See previous editions here. To view this newsletter in your browser, click here.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

More perspectives on today’s topic & other resources

Washington Post writer Christine Emba noticed something alarming about the men around her: “They struggled to relate to women. They didn’t have enough friends. They lacked long-term goals,” she wrote.”Some guys — including ones I once knew — just quietly disappeared, subsumed into video games and porn or sucked into the alt-right and the web of misogynistic communities known as the ‘manosphere.’” To put it bluntly, men are lost. In this piece, Emba tries to elucidate how we got here, and how men might find their way out of the wilderness.

Other interesting stuff

If you’ve tried to find a therapist recently who fits your specific needs, takes your insurance and has an immediate opening, you already know it can be “as rare as an orca spotting,” writes Michelle Baruchman for the Seattle Times. The paper attempted to contact 400 therapists listed by insurance companies in the Seattle area — and found only 32 confirmed openings for new clients seeking outpatient mental health counseling.

Group Therapy is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional mental health advice, diagnosis or treatment. We encourage you to seek the advice of a mental health professional or other qualified health provider with any questions or concerns you may have about your mental health.

Get Group Therapy

Life is stressful. Our weekly mental wellness newsletter can help.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.