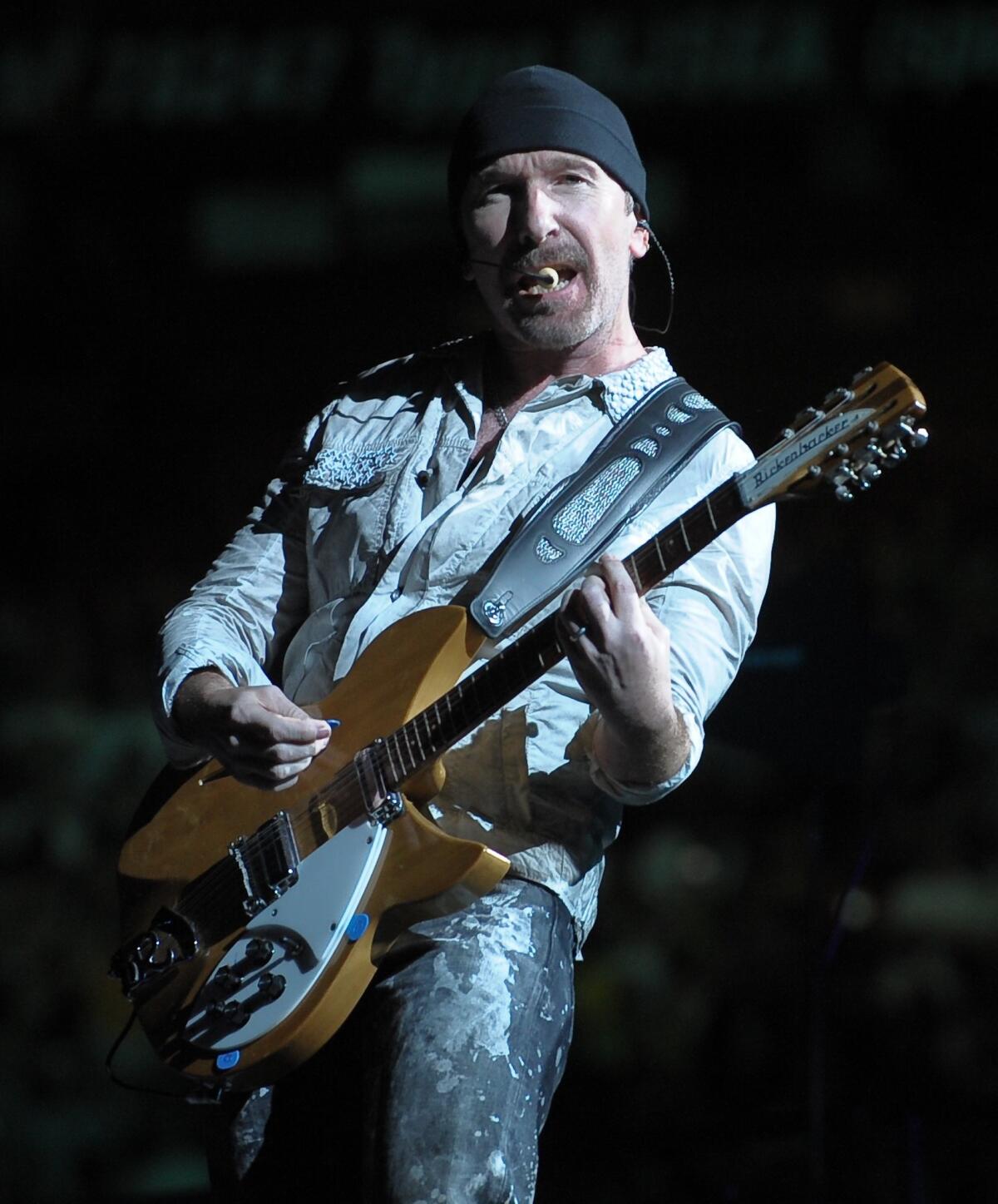

Column:: The Edge’s plan for Malibu rock and roll colony is dead. Here’s how U2 guitarist can win new fans

He’s rich.

He’s famous.

He wanted to build a colony of castles on a Malibu hillside, despite the years-long screams of conservationists.

But David Evans, who strums a guitar for U2, has become an exception to the rule that with money and power, you can buy anything your heart desires.

It’s been two weeks since the California Supreme Court delivered a near-fatal blow to Evans’ planned rock and roll colony on Sweetwater Mesa, which overlooks the Malibu pier and offers heavenly coastal views on a plot just outside the city of Malibu.

The court decided not to review a lower court ruling that the California Coastal Commission, which gave Evans the go-ahead in 2015, did not have the authority to do so.

So what happens next?

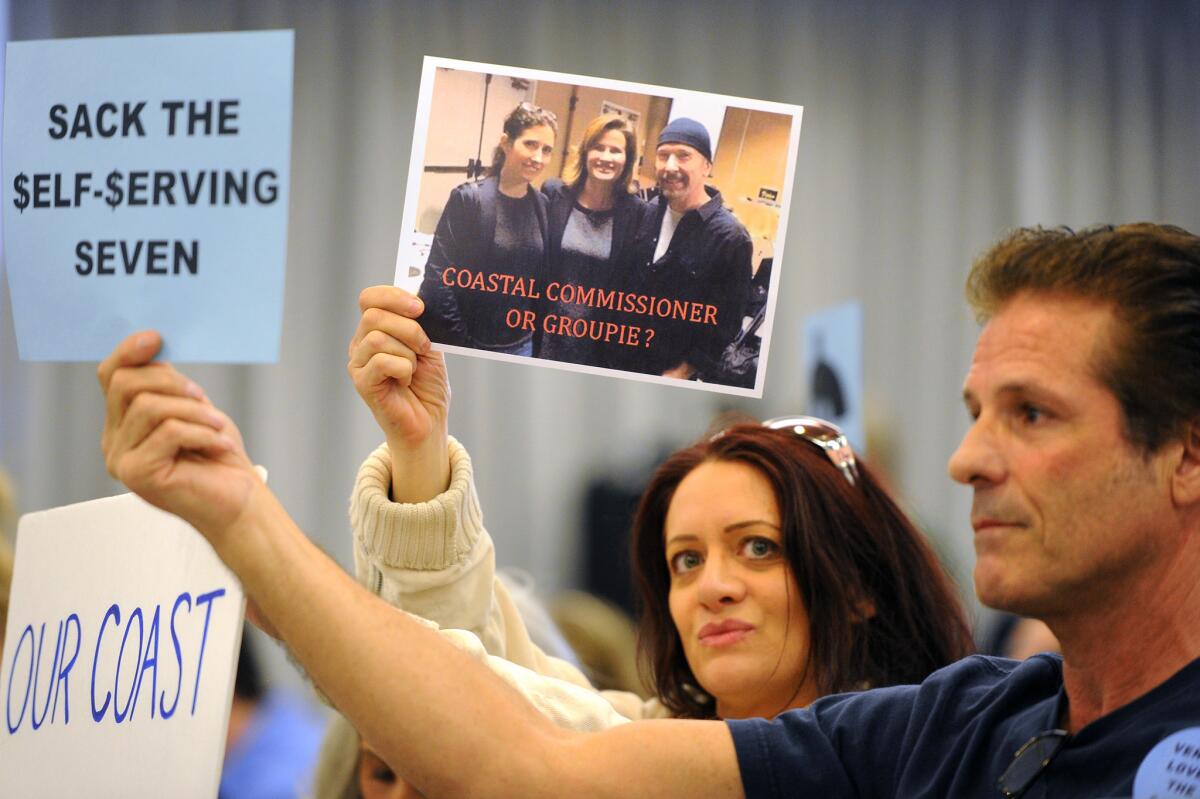

Unclear. I asked Evans’ attorney and he said he had passed along my query to his client. But in all the years I’ve been on this story, I’ve never been able to get hold of Evans. Maybe I should have gone to a U2 concert in Ireland, like Mark Vargas did. He’s the California Coastal Commissioner who met with Evans in Dublin and then came home to cast a vote in favor of the project. He said he paid for the Dublin trip and concert himself.

It just so happens that I have a few suggestions on what Evans might do next, but let me back up before I move forward, because there’s a David and Goliath story to be told.

Evans and his wife bought the 150 acres of land for just under $9 million in 2005 and were part of a plan to erect five ridiculously gigantic homes on an otherwise pristine ridge. If that’s not offensive enough, he wanted to call the compound Leaves in the Wind.

The Coastal Commission took a look at Evans’ plans—which included running a long water-service line through the hills, and sinking dozens of caissons into a cliff to support an access road — and said, in effect, you’ve got to be kidding. The commission rejected Evan’s claim that there were five separate owners, contending instead that limited liability corporations were used to mask his role as the only owner.

But legal maneuvering aside, Peter Douglas, the agency’s executive director at the time, zeroed in on what was really at stake.

“In my 38 years with the commission,” Douglas said at the time, “I have never seen a project as environmentally devastating as this one.”

When you’re a big-time rock and roller, though, you must get used to having your way. Evans didn’t back down. He scaled back the size of the homes and hired a big-shot architect to design a more natural, eco-friendlier development.

And that’s not the only person Evans hired.

My colleague Jack Dolan did some math three years ago and determined that Evans paid more than 60 lawyers, lobbyists and environmental consultants over the years. His minions filed more than 70 technical reports in an effort to convince the Coastal Commission that the project would not severely impact the habitat or be a major eyesore.

Evans hired the high queen of Coastal Commission lobbying, Susan McCabe, to do his bidding. He donated a piece of the land to extend a public hiking trail and silence some critics. He gave a tour of the property to one of the weakest links on the Coastal Commission — Roberto Uranga of Long Beach. And he met with Commissioner Vargas backstage at the concert in Ireland.

Late in 2015, the commission voted 12-0 in support of Evans’ project. In a historic low point for California coastal conservation, Commissioner Wendy Mitchell posed for a photo with Evans and apologized for how long the approval took.

Goliath won that round. But David did not throw away his slingshot.

The Santa Monica Mountains Task Force of the Sierra Club raised money to hire Dean Wallraff of Advocates for the Environment, a public interest law firm with just two lawyers.

“Dean reduced his hourly rate,” said Eric Edmunds, chair of the Task Force. “Nobody else stepped up to the plate and … we have a long history of fighting what we consider to be unwise … developments.”

Many suspected the odds of victory were long. But when I first got in touch with Wallraff, he was optimistic, and he remained so even after losing the challenge two years ago in Superior Court.

Wallraff challenged that decision in state appellate court, arguing that a full environmental impact report was not done, and that the coastal commission’s approval of the project was based on a flawed interpretation that it didn’t have the authority to deny a building permit.

Wallraff won in March, but not on either of those two points. The appeals court ruled that the Coastal Commission did not have approval authority, only the county did, because it had a coastal protection plan in place.

Evans then appealed to the state Supreme Court, which decided two weeks ago not to take the case.

But that doesn’t mean Evans is finished charging up the hill.

He can restart the process from scratch, taking his project to county officials this time, although Supervisor Sheila Kuehl is on record with “deep concern and opposition” to the project. Evans might have a chance if he agrees to build a single home instead of gashing the mountain with a small subdivision, but that could take years.

Or the guitarist can learn a new chord.

“I’d like to see it become part of Malibu Creek State Park,” said Mary Wiesbrock, chair of a group called Save Open Space and a longtime critic of Evans’ hilltop hallucination.

That’s a terrific idea, especially given the loss of mountain habitat to development and wildfires. Just this week, The Times reported on the threat of extinction for Central and Southern California mountain lions “in ever-shrinking islands of habitat hemmed by freeways and sprawl.” Evans, estimated to be worth a few hundred million bucks, could donate his land to the state, preserve some running room for the cougars, and instantly go from dastardly developer to crowd-pleasing conservationist.

“It’s not for me to tell somebody what to do with their land,” said Edmunds. “But there certainly are attractive tax advantages to donating” land for conservation purposes.

Malibu Mayor Jefferson Wagner, who took me up to Evans’ land years ago to make an argument for preserving its breathtaking natural beauty, suggested that Evans follow the lead of James Cameron. In 2014, the movie director sold 700 acres of Puerco Canyon land to public agencies for half his asking price. That land is now called Cameron Nature Preserve.

“Name a park after yourself and donate it,” said the mayor. “And all the environmental people say ‘thank you, you’re cool.’”

Who knows? I might even write a column about it.

Steve.lopez@latimes.com

Get more of Steve Lopez’s work and follow him on Twitter @LATstevelopez

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.