Great Read: Drivers for L.A. County’s sheriff found inside access a mixed blessing

Joseph Fennell was at his desk at the Compton sheriff’s station one night in February 2003 when a higher-up called: “I need your resume. Now.”

The 41-year-old sergeant frantically updated his work experience and sent it in. When he found out what the job was — driver for Sheriff Lee Baca — he was underwhelmed.

“I just thought, ‘What do you do, drive the sheriff around?’” he recalled recently.

It was much more than that, he soon realized.

For the next two years, Fennell crisscrossed Los Angeles County with Baca in the passenger seat, working a job that is little known to outsiders but carries such mystique that it remains a defining slice of the drivers’ biographies even decades later.

As the keeper of Baca’s cellphone, Fennell told top brass to try again later if the boss was in a bad mood. He was there when colleagues bragged about themselves in hopes of a promotion. At public events, he scanned the room in case anyone tried to harm the sheriff.

The hours were so punishing — 5 a.m. to 11 p.m. on a typical day — that Fennell’s wife quit her job as a registered nurse to care for their two children.

In return, Fennell got an intimate view of the sheriff, from his penchant for El Pollo Loco to his concern for the homeless to the flaws that helped lead, years later, to his downfall.

In an 18,000-person department troubled by cliques and favoritism, the job was never advertised. Instead, new drivers were tapped on the shoulder, usually because they had once crossed paths with someone influential. They were always men, often tall and strapping.

They were considered Baca’s chosen ones. As they progressed through the ranks, there were whispers that former drivers got more than they deserved because of their close association with the sheriff.

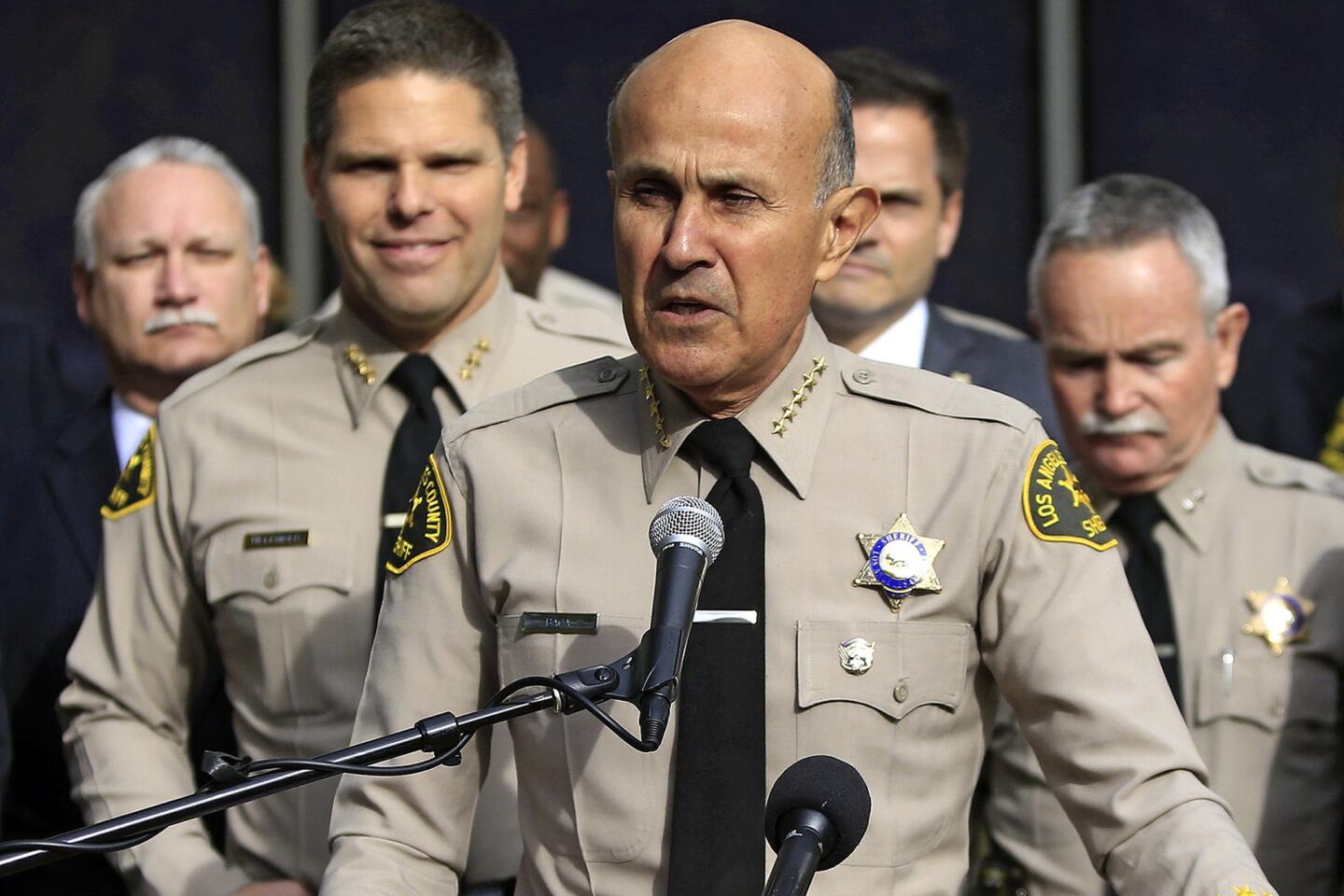

The job symbolized the old way of doing things under Baca, who retired abruptly in January 2014 after a series of scandals that culminated in criminal charges against more than a dozen of his deputies.

The new sheriff, Jim McDonnell, has pledged to stamp out any remnants of the boys’ club and create a meritocracy.

He began with the person who would be sitting next to him in the driver’s seat.

::

As Baca’s first driver, Pat Maxwell wore out a Mercury Marquis in a year, logging more than 70,000 miles shuttling from patrol stations to government meetings to community events.

While Baca was out for his morning run, Maxwell was catching up on the events of the previous night so he could prepare the sheriff for the day ahead. A daily 6 a.m. briefing was part of the driver’s portfolio.

In 1998, getting around the county’s 4,000 square miles required flipping through a Thomas Guide, making for stressful moments when the place was hard to find. When Baca ran late, which was often, Maxwell would discreetly prod him by handing him a three-by-five notecard that sometimes read, “We need to go now.”

There were exciting moments, such as the time the pair happened upon an armed robbery suspect on the Santa Monica Freeway. Maxwell, who had spent much of his career as a street cop, let his boss slap on the handcuffs.

There were the conversations about internal investigations, personnel moves and other topics that someone of Maxwell’s rank wouldn’t normally overhear. During all those hours in the car, Baca treated his driver as a sounding board, dispensing advice and asking for it.

Then there was the boredom — the hours sitting in tedious staff meetings or waiting outside fancy dinners. Baca steered clear of coffee and rarely drank alcohol, other than an occasional sip of wine, former drivers said.

“Everyone thinks it’s a glamorous position,” former driver Michael Claus said. “Glamour is not sitting in the car for three hours.”

Former drivers remember being ordered to pull over so Baca could talk to homeless people and give them money. Sometimes, the sheriff requested a detour to the houses where he grew up so he could reflect on his humble origins.

He also was inclined to take people’s statements at face value and refused to believe anyone had hidden intentions, former drivers said. That trait did not serve Baca well when he relied heavily on trusted aides as the county jails spiraled out of control.

::

Membership in the exclusive club of sheriff’s drivers had its perks but could also be a burden.

Fennell, the department’s first African American driver, said that after his driving stint, the sheriff treated him like a grandson, scolding him for mistakes while harboring deep affection for him.

Bound by their experiences behind the wheel and the scrutiny that followed, as well as their loyalty to Baca, the former drivers gathered for a luncheon every year at The Palm steakhouse, with Baca as the guest of honor.

Baca occasionally tapped former drivers for important jobs, as when Fennell and a predecessor, Jim Hellmold, landed two of the four spots on a task force to address violence in the jails.

“People dismiss your hard work sometimes,” said Fennell, now a commander in the countywide services division. “No matter what job I get, they always think it’s because I was the sheriff’s driver.”

At the LAPD, Daryl Gates was William H. Parker’s driver in the 1950s before eventually becoming chief himself. In his memoir, Gates described Parker as a father figure, but one who sometimes drank so much that his young driver had to guide him up the steep hill to his house.

Maxwell, now a commander in the South Patrol Division, said he sometimes wishes he had never been Baca’s driver.

“In a lot of ways, if I had to do it over again, I wouldn’t have done it,” Maxwell said.

Hellmold, especially, rose quickly, skipping a rank to become an assistant sheriff at age 46. On his way out, Baca named Hellmold as one of two possible successors for the sheriff’s job.

Those triumphs came to haunt Hellmold, who ran for sheriff against McDonnell. The day after losing the primary election, Hellmold was demoted by Interim Sheriff John Scott, who stated publicly that Hellmold needed more seasoning.

The next day, Scott transferred another former driver, Capt. Eli Vera, from the South Los Angeles station to the less prestigious reserves bureau.

Vera said his transfer was a complete surprise. In an evaluation a few months before, he had received the highest rating of “outstanding” and was praised for his “vast knowledge and command of situations,” he said.

Hellmold said he had earned his position and had plenty of experience despite his rapid rise.

“I worked early mornings for more than half my career. I was on the front line,” he said. “Then for the sake of internal politics, people want to accuse you of promoting because you were a sheriff’s driver for one year.”

Scott said in a recent interview that he was “putting people in the right seat on the bus” and that their ties to the previous sheriff were not a factor.

As the end neared for Baca, one of his former drivers turned against him. Maxwell testified to a blue ribbon commission about the problems in the jails, which included repeated instances of deputies brutally assaulting inmates.

“My No. 1 loyalty is to the Sheriff’s Department, above and beyond any sheriff or individual,” Maxwell said recently.

Baca declined to comment for this story.

::

Nine months after Baca’s sudden departure, a department-wide email caused a stir. There was an opening on the sheriff’s security detail for a deputy with an impeccable driving record and the ability to work an extremely flexible schedule, the Oct. 6 email said.

Drivers had always been plucked from the ranks by high-ranking officials or former drivers. Never before had the job been open to all.

McDonnell was still a month from being elected sheriff but was considered a lock after trouncing his rivals in the primary. The interim sheriff asked McDonnell how he would like to select his drivers. McDonnell said that he suggested some changes, including the job announcement.

“It was fairness — to open it up and give everybody a shot at what is considered a good job,” McDonnell said.

McDonnell spent much of his career at the Los Angeles Police Department, where recent chiefs have opted for a Secret Service-like detail rather than a single young protege. He’s taking a similar approach at the Sheriff’s Department.

His drivers work in teams, both for security reasons and to cut down on fatigue. From 40 or so applicants, McDonnell selected a handful, including the first female driver, Deputy Janine Hanson.

“For the department to see a female in this position, to see change in this way, was refreshing,” said Hanson, 42, who is often spotted at public events flanking the sheriff with her driving partner, Sgt. Clipper Hackett.

Despite McDonnell’s efforts to democratize the job, the driver label may not be easy to shake.

“It will follow everyone. No matter who the sheriff is, they’ll always wear that jacket,” Maxwell said. “They’ll always be referred to in the rest of their careers as sheriff’s drivers.”

cindy.chang@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.