‘American Sniper’ trial raises questions about veterans, PTSD and firearms

Joe Washam recently went hunting at a south Texas ranch with fellow veterans, including some suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder.

Washam, a former Army sergeant who developed PTSD after he was wounded in Iraq, noticed one man’s hands shake.

------------

FOR THE RECORD

Feb. 10, 8:23 a.m.: An earlier version of this article stated that veteran Joe Washam saw a man’s hands shake as the man held his gun while hunting. He did not see the man holding a gun.

-------------

At lunch, Washam watched the soldier, who was also coping with PTSD, sit uneasily with the restaurant door at his back.

“He was clearly shaken up,” Washam said. “He was like, ‘I’m OK, I’m just going to keep looking over my shoulder.’”

Yet by hunt’s end, the man was elated: He had shot his first deer.

Some veterans with PTSD and other trauma related to military service said hunting and shooting help them recover, but doctors are divided on the issue. The practice has drawn national scrutiny after a troubled veteran taken to a firing range was charged with shooting “American Sniper” author Chris Kyle, 38, and another man on Feb. 2, 2013.

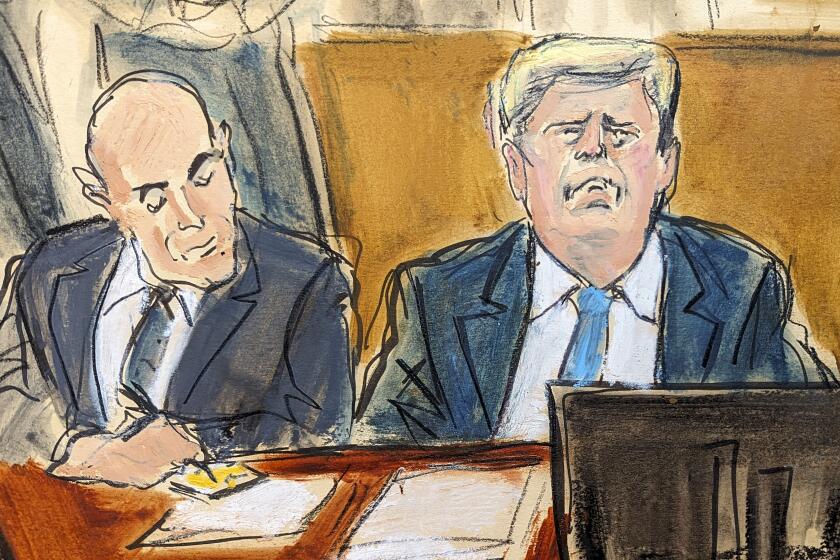

That veteran, Eddie Ray Routh, 27, is scheduled for trial here Wednesday in the killing of the former Navy SEAL and his friend Chad Littlefield, 35, at the Rough Creek Lodge and Resort shooting range Kyle helped design in Glen Rose, about 75 miles southwest of Dallas.

Routh’s attorneys have said they plan to pursue an insanity defense, presumably based on his time as a Marine serving in Iraq and Haiti. Prosecutors are not seeking the death penalty.

Routh’s relatives, attorneys and prosecutors declined to comment, citing a court gag order.

The sniper’s widow, Taya Kyle, 40, lives with their two children in the Dallas-area community of Midlothian.

“Chris both lived and died trying to help his fellow veterans,” Kyle’s family said in a statement last week, adding that the sniper known as “the legend” had “made personal sacrifices to preserve the American way of life.”

The trial has some emotional significance for Washam, a 34-year-old student at the University of North Texas who met Kyle on an antelope hunt with other veterans five years ago.

Washam had heard about Kyle’s reputation as the most lethal sniper in U.S. history after four tours of duty in Iraq. But during the hunt, Kyle was “jokey,” he said, “laughing at little stuff.”

“It wasn’t about him,” Washam said. “He just wanted everyone to have a good time.”

Every veteran shot an antelope, Washam said, and the hunt showed Kyle “had a big heart, wanting to help a community of guys, wounded warriors.”

Washam had been burned over 40% of his body during an explosion in Iraq in 2004. He had to learn to walk again and to regain use of his injured hands.

“I don’t have fingerprints,” he said, “but I can squeeze the trigger.”

Firearms were a pleasant reminder of his military training, but also “something you can have control of.” For one veteran he knows, shooting was an outlet that helped him stop drinking heavily.

“Every time a round goes off, that gunpowder smell, something about that for me — I love that smell,” Washam said. “It’s a comfort smell.”

But some veterans “don’t want anything to do with firearms, fireworks, loud sounds,” Washam said, while others “will go to the range but they won’t hunt. They say, ‘I don’t want to kill anything ever again.’”

Kyle had been scheduled to attend a veterans’ shooting event the weekend after he was killed. The shoot went off as planned, but Washam also noticed a bit of a backlash.

A Texas landowner who had hosted a deer and duck hunt for Washam telephoned, worried that he had allowed “a complete stranger” on his property with a gun, saying, “That scares me.”

Washam worries that with the popularity of the Oscar-nominated “American Sniper” movie and publicity surrounding Routh’s trial, veterans will not be trusted to hunt and target shoot.

Jacob “Jake” Schick, 32, a Shreveport, La., native who grew up hunting and works with other wounded veterans through the University of Texas’ Center for Brain Health in Dallas, said he too was worried about the fallout.

Schick, who was wounded by a tank mine explosion in Iraq, said it could be “good therapy for wounded warriors to squeeze off a few rounds. For some guys, it really helps release some stress.”

Schick appears in the movie firing a rifle at a range and turning triumphantly to Kyle, played by Bradley Cooper.

“Who’s the legend now?” Schick says, an ad-libbed line in a scene Schick says was filmed by director Clint Eastwood in two takes.

“The whole point of the scene was to show that there’s healing there,” said Schick, who knows Kyle’s family and still hunts with fellow veterans.

Up to 15% of recently returning veterans have been diagnosed with PTSD, in addition to those suffering from traumatic brain injuries, depression and other types of mental illness, according to Dr. Farris Tuma, chief of the National Institute of Mental Health trauma research program in Rockville, Md.

Edna Foa, a professor of clinical psychology at the University of Pennsylvania who pioneered treatments for PTSD, recommended against hunting and shooting for such a veteran.

“All of a sudden he can get a flashback or a disassociation, even for a minute, and think he’s back in Iraq,” Foa said.

Even when a veteran seems fine, Foa said, “They cannot trust their own selves because they can have an internal trigger.”

Tuma said shooting should not be considered therapy, but was not necessarily dangerous for those with PTSD. He said vetting people before a shooting event could be as simple as having their doctor ask whether they were making plans to harm themselves or others.

Joe McCartney, 63, a former Marine sniper who served in Vietnam, was excused from serving on Routh’s jury last week because he suffers from PTSD. He owns guns and enjoyed hunting, but recently had suicidal thoughts andgave his firearms to his son.

Another excused juror, Nathan Goldberg, 33, served with Kyle in Iraq and still hunts with fellow veterans, but said that in some cases, “We don’t put a gun in their hands. Depending on their state, they might have a flashback where they don’t know where they are and you’re standing beside them, looking like the enemy.”

To raise awareness about aiding veterans, the advocacy group Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America is sponsoring screenings of “American Sniper.”

“It’s a tragedy what happened to Chris, but that’s why this film is so important — it shows the tragedy of war and of people coming home and struggling with PTSD,” group founder Paul Rieckhoff said. “People have this stigma that veterans are damaged, broken people. It’s something we struggle against every day.”

molly.hennessy-fiske@latimes.com

Twitter: @mollyhf

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.