Jail would be ‘inappropriate’ for Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl, general says during desertion hearing

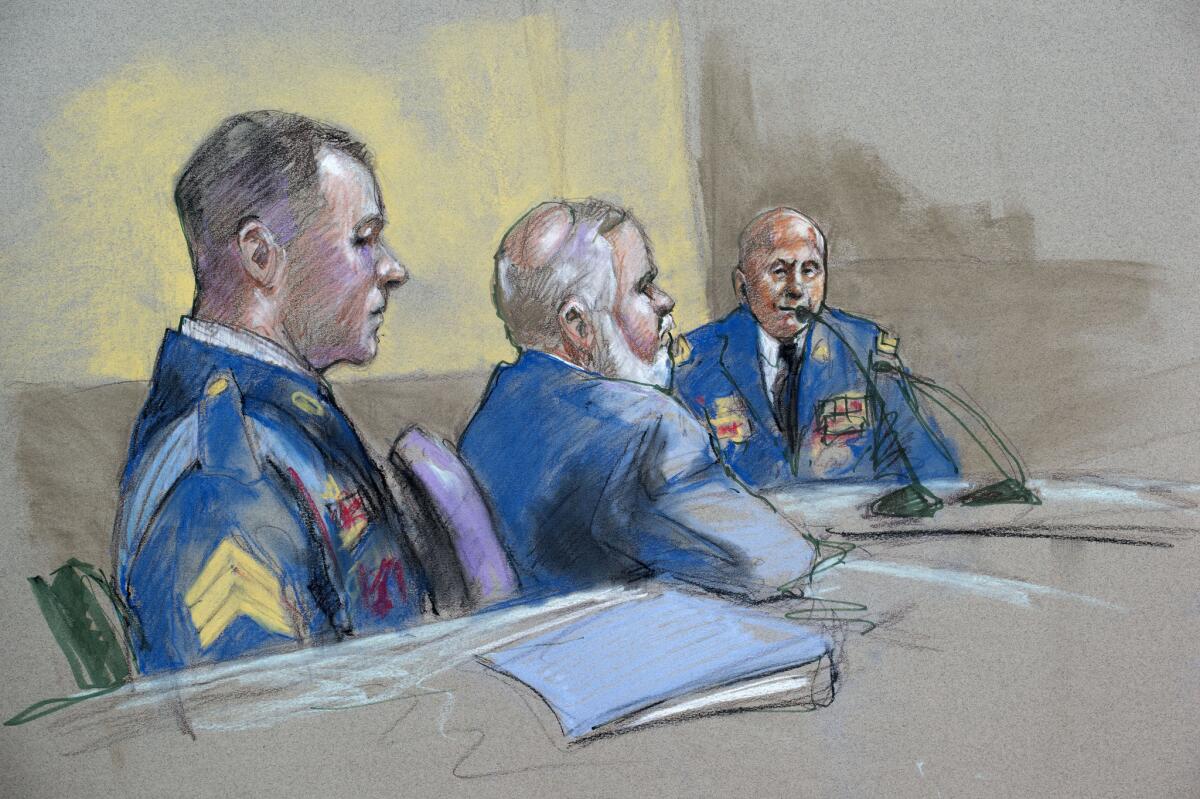

Army Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl, left, and defense lead counsel Eugene Fidell, center, look on as Maj. Gen. Kenneth Dahl is questioned at a preliminary hearing.

During the final day of testimony at a military hearing to decide whether Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl will face a court-martial on desertion charges, a general ordered to investigate his capture discussed his findings for the first time and testified for the defense about why Bergdahl does not belong in jail.

Maj. Gen. Kenneth Dahl said Bergdahl was “unrealistically idealistic” when he left his remote post in Afghanistan six years ago for a nearby base, hoping to draw the attention of a commander to problems that he believed were putting his unit at risk.

Bergdahl, now 29, was a private when he vanished June 30, 2009, and was captured by the Taliban and held for nearly five years by members of the militant Haqqani network. On Friday, an expert who debriefed him described the conditions as the worst endured by any captive since the Vietnam War.

Bergdahl was freed last year after President Obama agreed to release five Taliban prisoners, a controversial swap he defended even after the military announced Bergdahl would be charged.

Dahl said Bergdahl, whom he interviewed for a day and a half as part of his investigation, admitted during the interview that he had been “young, naive and inexperienced” at the time of his capture, and was “truthful” and “remorseful” about endangering fellow soldiers forced to search for him.

But Dahl noted that no soldiers died searching for Bergdahl and said he did “not believe there is a jail sentence at the end of this process” for the sergeant, calling it “inappropriate.”

Bergdahl’s lead defense attorney, Eugene R. Fidell of Yale Law School, said in his closing statements Friday that instead of a court-martial, his client should face a medical evaluation board and a less serious hearing for going absent without leave before his capture. He said the days Bergdahl spent in captivity are the greatest mitigating factor in his case, displaying the total on a screen: 1,797.

The defense also called a nurse practitioner who testified that she treated Bergdahl after his return for debilitating injuries he suffered in captivity to his shoulder, lower legs and back that rendered him “nondeployable.” The defense team said a military medical board found that at the time of his capture, Bergdahl also suffered from a “severe mental disease or defect,” although commanders testified that they were not aware of that.

Former Sgt. Greg Leatherman, who supervised Bergdahl, testified Friday that he had worried about him becoming alienated and tried to alert a superior, who dismissed his concerns.

The lead prosecutor countered that Bergdahl acted with “deliberate disregard” in abandoning his post and shirking hazardous duty, “exponentially endangered” fellow soldiers and upended the chain of command to get attention.

“He planned,” said the prosecutor, Maj. Margaret Kurz. She said that Bergdahl had purchased Afghan clothing for a disguise and had currency “for bribes,” and had mailed home his journal, books and his laptop before he left his post the night before his unit was due to return to the same base he is accused of heading for when he was captured.

She quoted from Bergdahl’s interview: “I’m going to get my chance to talk to a general.” She said Bergdahl’s victims include those who searched for him, and “the Army as a whole.”

“He has suffered greatly,” Kurz said, but added: “He still committed a crime and still needs to be held accountable.”

Hearing officer Lt. Col. Mark Visger, an Army lawyer, will recommend to the commanding general of U.S. Army Forces Command whether Bergdahl should face court-martial on charges of desertion and “misbehavior before the enemy,” which carries a potential life sentence.

Bergdahl did not testify at the hearing, but as he looked on, sitting ramrod-straight in his dress uniform, his face impassive, Dahl described what he learned about the soldier during a two-month investigation that included 57 interviews conducted with the help of nearly two dozen people.

The general spoke of a young man whose sheltered upbringing in Hailey, Idaho, shaped his view of not just the world but himself. Raised “at the edge of the grid,” home-schooled and denied normal social interactions, Bergdahl was “bright” and “well-read,” Dahl said, but introverted, with outsized expectations of himself and others.

He said Bergdahl emulated the individualist character John Galt in Ayn Rand’s “Atlas Shrugged,” who was “willing to sacrifice himself for the cause.” He said Bergdahl also mentioned his interest in the “samurai code,” which says “if you see what you perceive to be a moral wrong, you act immediately,” regardless of the consequences.

Bergdahl’s idealism was partly why, before joining the Army, he had “washed out” of the Coast Guard during boot camp, Dahl said.

Once he joined the Army, Bergdahl found fault with his training and commanders, but was “very motivated to deploy” and not “sympathetic to the other side,” Dahl said. Rather, he was frustrated that he couldn’t “play a bigger role.”

“Sgt. Bergdahl perceived a problem in the leadership of his platoon and that the problem was so severe that it put members of the platoon in danger,” Dahl said.

Bergdahl didn’t think he could turn to lower-level commanders, Dahl said, because he believed they were “only in it for the money, only in it for the rank.” So he left his gun behind and slipped out after 10 p.m., intending to run to the base 20 miles away, turn himself in and demand to speak with a general, Dahl said. Instead, by 10 a.m. the next morning, Bergdahl was captured, he said.

The soldier escaped and was caught twice, eventually locked by captors in a 7-square-foot metal cage for more than three years, according to Terence Russell, a Defense Department expert who debriefed Bergdahl.

Russell choked up as he described how Bergdahl was tortured: blindfolded, tied to a bed and beaten with a rubber hose and copper wire, denied food and water even as his muscles atrophied and he suffered “uncontrollable diarrhea” for more than three years.

While Bergdahl appeared in videos released by his captors, Russell said the soldier never disclosed classified information and did his best to comply with the Army’s code of conduct and resist.

“Sgt. Bergdahl did that — did the best he could do — and I respect him for it,” said Russell, who served for years as an Air Force survival instructor. “He had to fight the enemy alone. … You can’t underestimate how hard that is.”

molly.hennessy-fiske @latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.