For Muslims, bad memories and new worries

There are few Muslims in the small northeast Ohio town where Karen lives with her Palestinian American husband and their five children.

In a region where Amish and Mennonite women cover themselves, Karen and her 20-year-old daughter, Amanda, find the occasional rude remark about their head scarves more puzzling than annoying.

But what happened Tuesday to Karen’s youngest, 10-year-old Yusef, has her steaming.

The fifth-grader came home from school with a note that said he’d earned a punitive “strike” and spent time in detention.

Yusef told his family that his locker was searched and that he’d had to eat lunch alone in the library.

What had he done?

The column of the disciplinary notice marked “Incident” read: “Yusef said to his classmates, ‘I am going to blow up this school.’ ”

Yusef told his mother that he and some other children were sitting at a table in class, talking about the Boston Marathon explosion. One boy said, “Well, Yusef is going to blow up the whole school.” Yusef, shocked, said loudly, “What? I’m going to blow up the school?”

According to Karen’s son, the teacher heard him and turned to the other boy and asked, “What just happened? What did Yusef say?” And the other boy told her: “Yusef said he’s gonna blow up the school.”

I heard that story from Anum Hussain, 22, an American-born content strategist for Hubspot who also is the Boston regional director of the Muslim Interscholastic Tournament. After the 9/11 attacks, which occurred when she was in fourth grade, Hussain was called “Sadam Hussein’s niece” and told “go back to your country.”

Hussain heard about Yusef from his sister Amanda, who is studying psychology at Kent State. Amanda, by the way, said she especially identified with the Boston victims because she is a runner who completed a half-marathon in September.

I briefly spoke with Yusef on Wednesday evening. (Karen asked that I not use the family’s last name because she does not want to bring greater embarrassment to her son.)

Neither the principal nor Yusef’s teacher, he said, asked him for his version of events before punishing him.

Karen, a teacher at an Islamic school, is keeping Yusef home until she can straighten things out with the school.

Her husband, who recruits international students for a university, is traveling for business and doesn’t even know about it yet. After 9/11, she said, he pleaded with her to remove her scarf. She locked herself in for a week, afraid to leave the house, then compromised and wore a hat.

On Tuesday, Karen said, a school counselor left a vague message on her answering machine. Despite multiple attempts to reach the school, she said, no one had returned her calls by Thursday afternoon.

Let me hasten to add for those worried about molehills becoming mountains, the family is not looking for publicity. No one is making a federal case of this, no one is screaming civil rights violations, no one is threatening lawsuits.

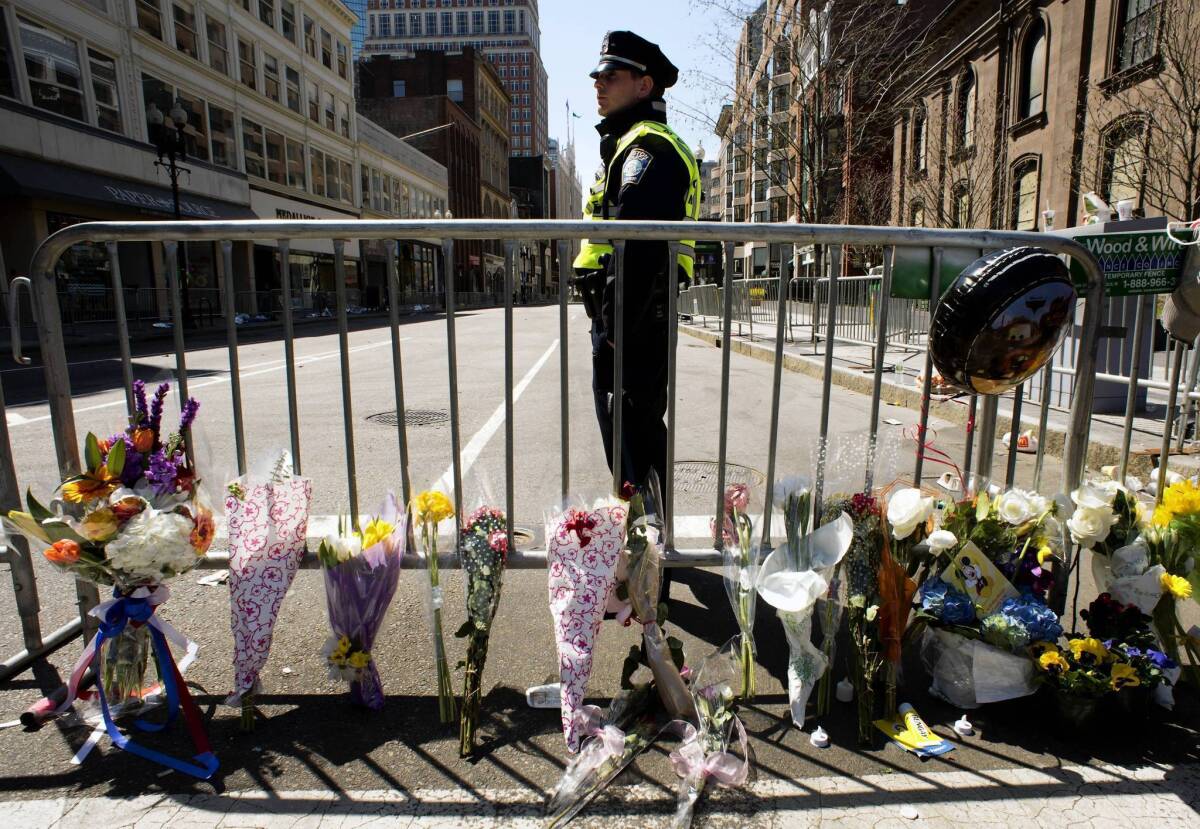

But you can bet this family, like many other American Muslims, is having 9/11 flashbacks — when they watched the horror in Manhattan and felt attacked as Americans, and then felt attacked for their faith.

When John King of CNN erroneously reported Wednesday that authorities had arrested a suspect, a “dark-skinned male,” many American Muslims surely shuddered.

“As soon as you say you are Muslim, people associate you with 9/11 and terrorism, and some fear you right off the bat,” 21-year-old Boston EMT Asmae El Alami told me Wednesday. A Muslim who was born in Morocco and immigrated to the U.S. at age 3, El Alami wears a head scarf while on duty. She was stationed in Brookline, south of Boston, on Monday, and was disappointed that she was not called to help blast victims.

Late in the day, she got a call from a former partner. “He said, ‘As soon as this happened, I thought about you and knew you were going to get treated like crap.’”

It’s a worry reinforced by experience.

In the months after 9/11, the FBI reported a 1,600% increase in anti-Muslim “hate crime incidents,” according to a 2011 report by the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division. And though the number of complaints soon tapered off, other kinds of bias complaints are on the rise. Allegations of anti-Muslim bias in the workplace are higher than ever.

Department of Justice figures also suggest that anti-Muslim “zoning bias” — where towns refuse to grant building permits for mosques — is a growing problem. In 2011, neighbors of a proposed mosque in Murfreesboro, Tenn., according to the report, challenged the permit on the grounds that Islam “was not a religion entitled to 1st Amendment protection, but rather a political ideology committed to turning America into a sharia state.” A judge dismissed the case.

Shareef Elnahal, 27, a first-year internal medicine resident who helped triage explosion victims with ruptured eardrums and major limb injuries on Monday at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said he was dismayed when fingers were so quickly pointed at a young man from Saudi Arabia, a blast victim who was rumored to be a patient at his hospital.

“We do hope that whoever is responsible is found, even if it is a Muslim,” Elnahal said. “On the other hand, we are hoping it’s not a Muslim, because it’s gonna set us back as a community for all the progress we’ve made in the last 12 years.”

Should the culprit in this case turn out to be a Muslim motivated by anti-American sentiment, it’s worth remembering the words of former President George W. Bush, uttered in the days after 9/11: “Those who feel like they can intimidate our fellow citizens to take out their anger don’t represent the best of America, they represent the worst of humankind, and they should be ashamed.”

For her part, Karen is planning to invite Yusef’s principal and teacher to a community dinner Saturday hosted by her local Islamic society. The flier for the dinner puts it nicely: “Bring an open heart, a desire to listen, and a dessert (no gelatin, lard or pork).”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.