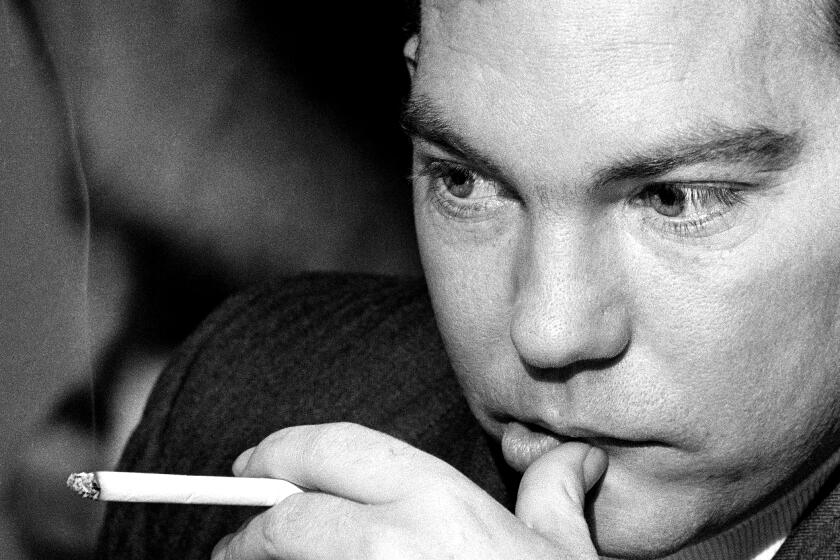

Larry Field, developer and Frank Gehry associate who changed the L.A. skyline, dies at 89

Larry Field, a prominent Los Angeles developer who led the way on converting aging industrial warehouses into creative work spaces, worked repeatedly with architect Frank Gehry and poured his resources into L.A’s cultural institutions, has died at his home in Beverly Hills.

Forever tinkering with the city’s skyline, Field was still hard at work when he died Tuesday at age 89.

The son of immigrants who grew up stocking shelves in his parent’s tiny grocery store in the Bronx, N.Y., Field arrived in L.A. in 1965 when the city was filling up with new arrivals and homes couldn’t be built fast enough.

One of his first projects was a two-block stretch of beaten down storefronts along the Venice boardwalk — 7 1/2 acres in all for $1 million. His first tenant was Gehry. The two became lifelong friends and work associates.

“He didn’t know real estate, and I didn’t know architecture,” Field told The Times. “It was perfect.”

Years later, Field found a former BMW facility in Playa Vista that had seen better days and the two converted it into Gehry’s new, expanded work space. It became a model for converting abandoned, often cavernous warehouses and research facilities into airy work environments.

In 2017, the two teamed up again on repurposing a tired-out Xerox warehouse in El Segundo, turning it into a free-flowing, wide-open business campus called Ascend. Gehry, who was responsible for the sprawling, open-floor Facebook campus in Menlo Park, designed the building.

Lawrence N. Field was born Oct. 21, 1930, and raised in the Bronx. His parents had both fled Hungary during a time of upheaval after World War I.

In his autobiography, Field said they arrived penniless, unable to speak but a word or two of English and without any natural job skills. His father worked as a waiter until he saved enough money to buy a small grocery store, arriving at work each day in a coat and tie. Through life, Field noted in his autobiography, he remained deeply touched by the story of immigrants seeking a better life in America

He attended what was then City College of New York, later enlisted in the U.S. Army, and got a job selling Dove soap for Lever Brothers, which he hated so profusely he tried to get fired so he could collect unemployment. When that didn’t work, he quit and got into real estate.

In Southern California, he built and financed hundreds of homes, mostly through his firm NSB Associates, named for his typical response when asked how thing were going: “Not so bad.” He also used the phrase on his 2019 autobiography, “Not So Bad — From the Bronx to Beverly Hills.”

Field and his wife, Eris, became generous philanthropists. When she was diagnosed with diabetes in the mid-1980s, they provided a $2.5 million endowment for the Eris M. Field Chair in Diabetes Research at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. They founded fellowships at his alma mater and in Israel and gave money to the Music Center in Los Angeles, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the Hammer Museum, Walt Disney Concert Hall and the Jewish Federation of Greater Los Angeles.

His wife died in 2009. Field is survived by two daughters, Lisa and Robyn; two granddaughters and his companion of 10 years, Rivka Seiden.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.