Op-Ed: Do nutritional labels work?

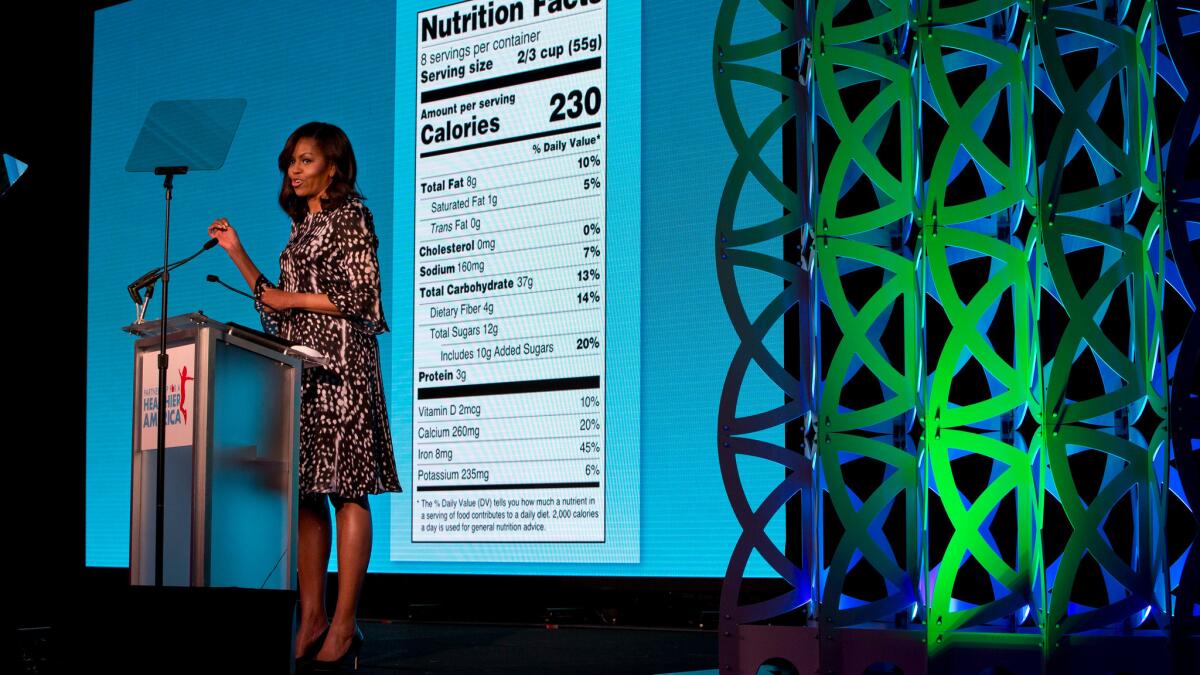

The Food and Drug Administration recently unveiled significant changes to nutritional labels. After a hard-fought battle, the new labels will give consumers greater insight into how much added sugar is hidden in the food we eat. Calories will be displayed more prominently and serving sizes will better reflect actual portion sizes. Public health advocates, consumer groups and the FDA have touted these new requirements as essential to combating America’s obesity epidemic.

The only problem is that these new-and-improved labels may not help those who need nutritional information the most.

To grasp the details on the back of a bag of chips or a can of soda, a consumer needs to understand grams and complicated ingredient names, calculate how many servings the item contains, and put everything together in the broader context of the amount he or she consumes each day. These calculations require English and math skills, time and motivation.

It should come as no surprise, then, that consumers who are already more informed about the connection between diet and health are more likely to take advantage of information presented on nutritional labels, or that people who already eat healthfully tend to use labels more than others. Research reveals that factors such as income, gender, age and race also influence label use.

A study published in 2010, for instance, showed that about 65% of whites report using labels, compared with 41% of Mexican Americans and 55% of blacks. The same study found that about half of low-income respondents report using labels, compared with 70% of high-income people.

The same patterns hold for calorie counts at restaurants. Much of the research on this subject comes out of New York City, the first jurisdiction to require large chains to post calories on menus and menu boards in an effort to steer consumers toward healthier choices.

Even though New Yorkers notice and favor menu labeling, only wealthier patrons seem to actually use the information. For example, menu labeling reduced the calories purchased at Starbucks, but not at McDonald’s, Burger King, Wendy’s and KFC. (Starbucks attracts a more educated, more affluent clientele than fast-food establishments.)

Similar patterns were found in Philadelphia, where menu labeling does not seem to have altered purchasing behavior among black, high school-educated fast food customers.

We shouldn’t accept the simple notion that more information is always better.

Thanks to the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act, we’ve had nutritional labels in this country since the early 1990s. Yet over two decades, research shows a widening nutritional quality gap between the diets of college-educated Americans and those of people with a high school diploma. The gap in obesity rates between minority communities and whites has also widened. There’s no reason to think the FDA’s new labels will improve the situation.

This is not to say that lack of information — or lack of ability to process information — is wholly responsible for poor diets. The link between nutrition and health is much more complex. Other factors play a role, including access to healthy foods, and influence from peers. Still, information matters. And while labels make information available for everybody, they apparently translate into healthier eating only for those who are best equipped to pay attention to the information and are motivated to act on it.

The answer isn’t to scrap transparency measures, but to improve them.

Public health advocates in Britain have recommended revising nutritional labels to include exercise equivalents. By switching to a more comprehensible metric — from calories to minutes spent exercising — they believe the information provided can be translated more easily into action.

And in fact there’s good reason to think the British experts are right. Black teens drink on average two cans of soda a day, which puts them at high risk of obesity. Researchers tried to change that by showing low-income black teens in Baltimore calorie information for each soda they consumed, including absolute calorie numbers, calories as a percentage daily value and calories expressed as an exercise equivalent. It turns out that telling teens they would need to run 50 minutes to work off a bottle of soda was the most effective way to steer them to healthier beverages.

Here in Southern California, the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health’s “Sugar Pack” campaign helped consumers visualize the number of table top sugar packets in each bottle of sugary drink. More than 60% of surveyed residents reported they were likely or very likely to reduce soda consumption as a result of the campaign.

We shouldn’t accept the simple notion that more information is always better. Unless it is comprehensible and actionable, transparency can end up empowering those who are already well-equipped to understand the information, and leave the rest behind.

Elena Fagotto is director of research at the Transparency Policy Project at Harvard’s Kennedy School. Follow @SunshinePolicy

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion or Facebook

MORE FROM OPINION

Cutting through the drug manufacturers’ smokescreen on SB 1010

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.