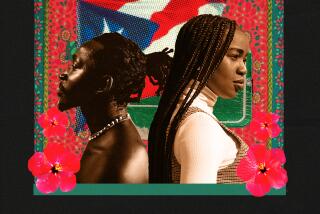

Op-Ed: In the Dominican Republic, suddenly stateless

A recent ruling by the Constitutional Court in the Dominican Republic to strip away the citizenship of several generations of Dominicans leaves no doubt that the nation has not left its history of abuse and racism behind.

According to the decision, Dominicans born after 1929 to parents who are not of Dominican ancestry are to have their citizenship revoked. The ruling affects an estimated 250,000 Dominican people of Haitian descent, including many who have had no personal connection with Haiti for several generations.

These Dominican citizens are suddenly stateless and without rights simply because of their Haitian ancestry. Dominican animosity and racial hatred of Haitians dates back to at least 1822, when the Haitian army invaded the Dominican Republic, liberated the slaves and encouraged free blacks from the United States to settle there to make Dominicans “blacker.” February 27, Dominican Independence Day, does not celebrate independence from Spain but independence from Haiti in 1844. On that day a nation that banned slavery and welcomed a diverse population was founded, but the people have been arguing about that diversity ever since.

In 1912, the Dominican government passed laws restricting the number of black-skinned people who could enter the country, but the sugar companies ignored the restrictions. Unscrupulous elite Dominicans looking for cheap labor for the mills brought in most of the Haitians. Those early laborers were kept in barracks lacking basic amenities and were deprived of all civil rights. It is mostly their offspring who are affected by the new ruling.

That racism against Haitians continued. Under dictator Rafael Trujillo, an estimated 20,000 Haitians were massacred over five days in October 1937 — to “cleanse” the border, according to the government. In 1983, President Joaquin Balaguer published the book “La Isla al Revés” (“The Island in Reverse”), claiming that the Haitians were trying to invade and that their secret weapon was “biological.” According to Balaguer, Haitians “multiply with a rapidity that is almost comparable to that of a vegetable species.”

In 1996, when José Francisco Peña Gómez, a popular Dominican politician with black skin and African features, ran for president, Balaguer insisted that Peña Gómez was an undercover Haitian spy with a secret plan to turn the Dominican Republic over to Haiti.

One of the important lessons of the Nazi Holocaust is that the first step toward genocide is to strip a people of their right to citizenship. What will happen now to these quarter of a million people who will be stateless? Will they retreat into hiding, submit to the old conditions of near-slavery in Dominican agro-industry or desperately attempt escape on boats, as reports from Puerto Rico suggest they are already doing?

The ruling will make it challenging for them just to live — to study, to work, to legally marry, to register their children, to open bank accounts — and even to leave the country that now rejects them, because they cannot obtain or renew their passports.

To the Dominican government, this is not such a great crisis. After all, it claims, the Haitian Constitution grants Haitian citizenship to anyone anywhere in the world who has Haitian parents. Even if this were automatic, which it is not, it would be like saying that there would be nothing wrong with stripping Jews of U.S. citizenship because they have the right to Israeli citizenship.

But to many Dominicans, this is a grave crisis, the reinstating of the old racism that many have fought against. To Dominican Americans, it is an absurdity. As Edward Paulino, a history professor at John Jay College in New York, said, “I, a Dominican American born and bred in the U.S., have a right to Dominican citizenship, but those born and raised in DR of Haitian parents do not.”

The court’s action violates standards of international law and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, which clearly state that people cannot be stripped of citizenship. Although the Constitutional Court cited a 2010 amendment on citizenship in its 38th Constitution in making the ruling, the decision violates Title II, Chapter 1, Article 38 of that same Constitution, which says all Dominicans are entitled to the same rights regardless of gender, religion, skin color or national origin.

How should the world react? Is it such a big thing — the life, liberty and pursuit of happiness of a few hundred thousand Dominicans? Should Western nations, starting with the United States, conduct business-as-usual with a country that commits such crimes against human rights? Would this be a suitable place to spend the family vacation, now that tourism has become a major Dominican economic activity?

Isn’t it time that the world tells the Dominican government that stripping people of their rights based on their ethnic background, setting up part of the citizenry for abuse and establishing an apartheid state is unacceptable? Is a nation building weapons of mass destruction or perhaps using chemical weapons on its own people the only line we will defend? Don’t we also need to recognize, as we learned in Germany, the Balkans and South Africa, that we cannot accept institutionalized racism?

Mark Kurlansky, Julia Alvarez, Edwidge Danticat and Junot Díaz are authors. Alvarez and Díaz are Dominican American; Danticat is Haitian American.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.