Op-Ed: An existential threat to American democracy and what the resistance needs to do

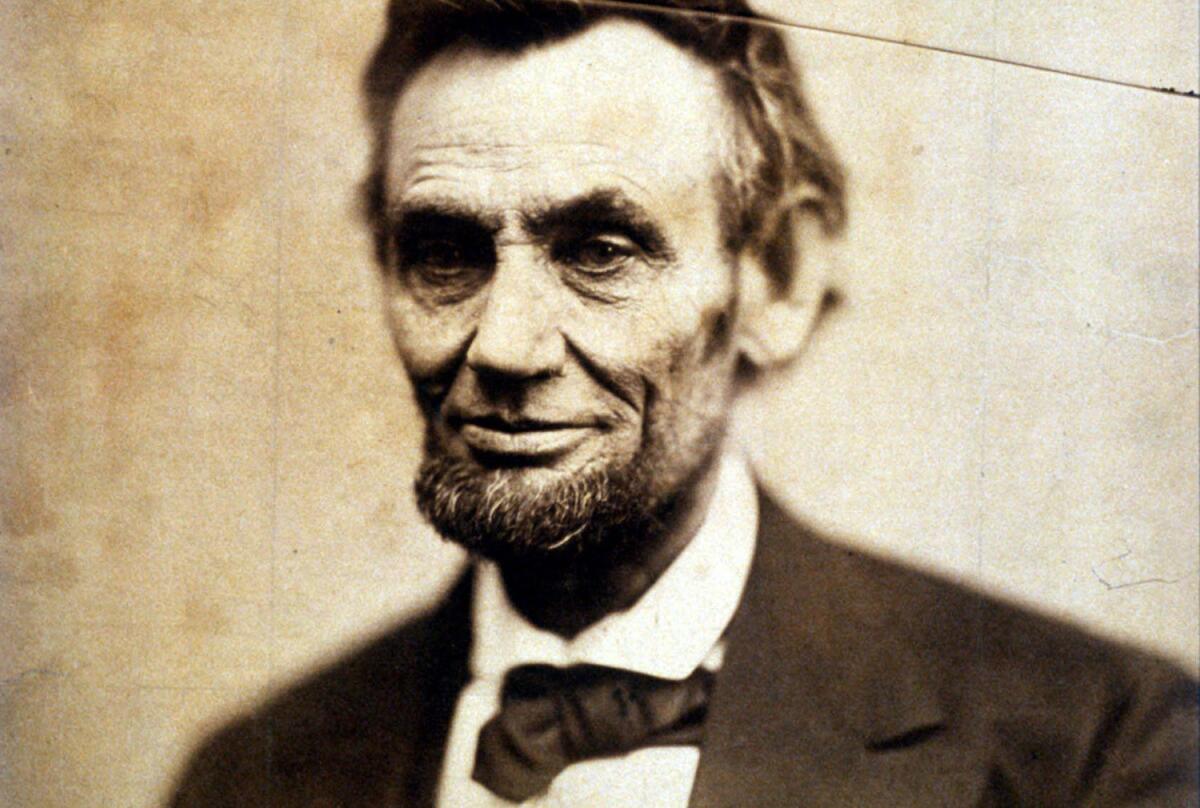

Less than 48 hours after the election results came in, thousands gathered to vow resistance. In downtown Savannah, Ga., on Nov. 8, 1860, under a huge flag inscribed with the motto “DON’T TREAD ON ME,” throngs cheered for a speaker who proclaimed: “The election of Abraham Lincoln and Hannibal Hamlin to the Presidency and Vice Presidency of the United States, ought not and will not be submitted to.”

Nearly all mainstream historians now agree that the Civil War was fundamentally a contest over slavery. That is true, but we should not ignore the war’s proximate cause: the refusal of a substantial number of Americans to accept the results of a presidential election.

I don’t think we are headed for a civil war like the one that began almost 160 years ago, but we are facing a similar moment of existential threat. Americans are accustomed to thinking of our elections, with a few exceptions, as moments of resolution: political and social strain are eased by the essential ritual of voting.

This is what the Constitution’s framers intended. As James Madison wrote in the Federalist Papers, the electoral system would be a hedge against “instability, injustice, and confusion,” especially at times when zealots and demagogues have “divided mankind into parties, inflamed them with mutual animosity, and rendered them much more disposed to vex and oppress each other than to co-operate for their common good.” Yet Madison’s formula works only if those zealots and demagogues concede to an election’s outcome.

Stoked by self-interested leaders and an inflammatory press, millions of white citizens in 1860 rejected Abraham Lincoln as their legitimate leader. A significant difference between that election and 2020 is that Lincoln wasn’t running against the incumbent president, the lame-duck James Buchanan. Rather, he faced a field of three weak candidates, none of whom had managed to fire up much grass-roots enthusiasm.

This year, we have an incumbent president running with a large, committed and aggrieved base of supporters. In some ways, this makes the potential election crisis that could play out this week more dangerous.

One lesson of 1860 is the dangerous power of sectionalism. Today’s sectionalism is as much informational as geographical: Thanks to the media and abetted by new technologies, the left and the right live within separate, closed ecosystems of reality. This was also the case in 1860. The invention of high-speed, steam-driven rotary presses in the 1840s meant that the United States soon had more than 4,000 newspapers — more than 10 times as many as in the 1820s. Even small towns had separate papers for each political party, each offering radically different versions of current events.

Another new technology, the telegraph, allowed editors to keep tabs on what was going on elsewhere in the country, dishing out selective tidbits that would fuel their subscribers’ appetite for outrage. Reports that proved false were corrected too late, or more often, never. Unscrupulous opportunists took advantage of this chaotic news environment to promote their own political agendas by inventing and amplifying falsehoods.

Almost immediately after the 1860 election, pro-slavery resistance groups formed and soon became the nucleus of the Confederate Army. Lincoln’s supporters responded too slowly, basking in the complacent glow of victory. Even after the Southern states began announcing their formal withdrawals from the Union, beginning six weeks later, most Northerners remained confident that the crisis would be resolved through ordinary political means.

What ultimately saved the Union — only barely — wasn’t a Supreme Court ruling, or a congressional compromise, or the intervention of ex-presidents and other respected bipartisan figures. It was the mass mobilization of citizens in Northern states, who rallied behind Lincoln and against secession after military hostilities began, taking to the streets in huge political gatherings that also served as recruiting events for Union Army regiments. He and millions of others recognized that if a group of citizens were allowed to nullify the results of an election simply because they didn’t like the outcome, it would render the entire democratic project nonsensical. Their eventual victory would come only at the cost of untold suffering and destruction.

As Lincoln would say at Gettysburg, the Union dead had sacrificed their lives not just so that this nation would endure, but so that democracy as an idea would not perish. That is how important a presidential election is.

This idea must burn as brightly now as it did then, even without Lincoln to articulate it. If Trump and his supporters brazenly refuse to accept the results of the presidential election, their opponents must not simply wait for the Supreme Court or Congress to resolve the impasse. Rather, each of us must resist as if the nation’s life depended on it, because it does.

Trump’s opponents must prepare for nonviolent resistance. A recent report by the bipartisan Transition Integrity Group found a high degree of likelihood that in the event of a Biden victory, Trump will contest the election result “by both legal and extra-legal means.” Countering this will be difficult, it warned. But the actions of ordinary citizens may be the key: “A show of numbers in the streets — and actions in the streets — may be decisive factors in determining what the public perceives as a just and legitimate outcome.”

We are becoming dangerously accustomed to conducting activism in the safe digital spaces of Facebook and Twitter, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. But enduring political movements can be established only in real spaces, not virtual ones.

Americans should prepare to rally — whether in Washington, state capitals, or small towns — in numbers even greater than for the 2017 Women’s Marches. The protests will need to be sustained, too. And they will need to be diverse. As we have seen with the Women’s Marches and many of the Black Lives Matter protests, large events that include families with children are much more likely to remain nonviolent than actions by smaller, less diverse groups.

Resistance will likely involve real risk, especially in the time of a pandemic. We can take guidance from the late Rep. John Lewis and his comrades on the Edmund Pettus Bridge. Their nonviolent resistance came at a cruel cost, but ultimately, they won a lasting victory for American democracy.

Adam Goodheart is the author of “1861: The Civil War Awakening” and the director of Washington College’s Starr Center for the Study of the American Experience.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.