Editorial: Give L.A. a little more money to help it take a lot less water

California has $1.5 billion to distribute to cities and local water agencies to help the state cope with increasing aridity and less predictable rainfall. Should at least a third of it go to Los Angeles to boost a historic water recycling project?

That’s an easy “yes.” $500 million in state funding would be a smart investment not just for residents of L.A. but for the entire state.

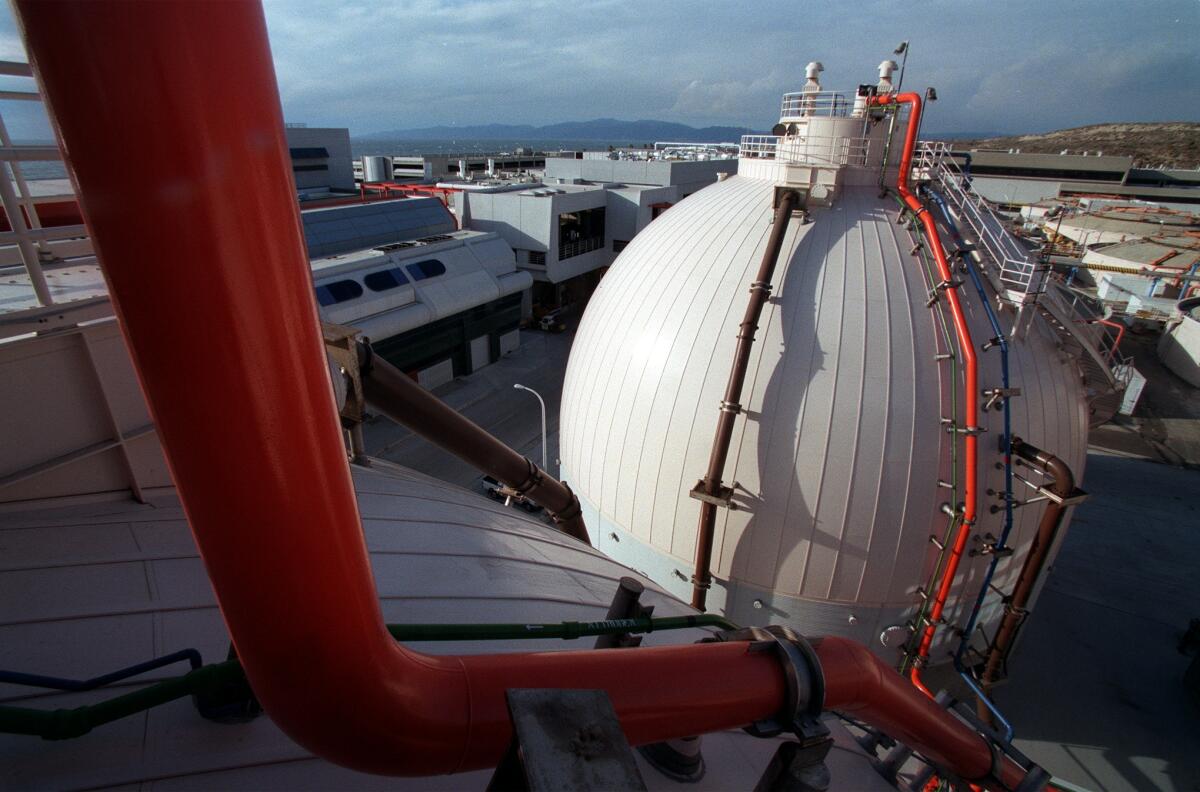

Much of the runoff from residents’ showers and other household uses currently is channeled to the Hyperion Water Reclamation Plant in Playa del Rey, where 250 million gallons of water per day are separated from all varieties of gunk, cleansed — and then shunted into the ocean, five miles from shore, where it mingles with seawater and is lost to us. City engineers and scientists have spent years preparing to amp up the plant’s cleansing power to turn it into a factory for water that’s pure enough to drink — purer than the stuff that comes from the western slope of the Sierra, through the California Water Project, or from the eastern slope, through William Mulholland’s Los Angeles Aqueduct and its extensions, or from the Rocky Mountains via the Colorado River and Lake Mead.

Those three earlier projects made Southern California into one of the wealthiest and most livable regions of the world, and an economic engine that powers the economies of the state and the nation.

A hotter planet is drying out Los Angeles and bringing the longtime slur against the city — that it is located in the desert — closer to the truth.

But we over-tapped the natural supply and have to repair the damage by keeping some of that distantly sourced water in place. It also turns out that the last century was a historical anomaly — unusually wet when compared with the millennia recorded in tree rings and geologic evidence. The climate is reverting to its drier norm at least in part because of human action and perhaps as part of the natural order as well. There is less water in Northern California and the Colorado River basin to import.

The defining 21st century water projects are those that will move us beyond imports and allow us to generate enough drought-proof supply for our drinking, showering, irrigating and flushing needs here at home. That means recycling of the kind that can and should be done at Hyperion. And at the Donald C. Tillman Water Reclamation Plant in Van Nuys and the Metropolitan Water District’s planned reclamation plant in Carson.

Large-scale recycling would help the state immensely by reducing the need for water from the Sierras or the Rockies, more of which could be left in place for local use and to sustain and restore struggling creeks and rivers and the migrating fish and other wildlife they support.

Hyperion alone, built out to its full potential, could supply 216 million gallons of pure water daily (a fraction will still go into the ocean). That’s a third of the city’s needs — putting the recycling project on the same scale as the last century’s aqueduct projects. It could come online as early as 2035.

But it won’t be cheap. The project known as Operation Next will cost about $16 billion and will need multiple sources of funding.

Much of the cost will be in the technology and energy needed to cleanse the water and to prepare storage underground in the northern San Fernando Valley. But a large portion of the cost will tackle one of the great challenges of Hyperion, which sits at sea level.

Los Angeles is considering ‘direct potable reuse,’ which means putting purified recycled water directly back into drinking water systems.

Much of L.A.’s imported water currently enters the Valley from higher elevations and can be distributed around the basin by gravity and pressure. That’s how wastewater flows to Hyperion as well. To distribute the recycled water, it has to be moved north again, against gravity, so that it can flow south. It will have to be pumped, and doing so will require more energy than what is currently sucked up by the state’s greatest single electricity user — the pumps that lift Northern California water over the Tehachapi mountains into the southern part of the state.

But L.A. is planning to do that — without fossil fuels or emissions.

Even with these costs, this project will still be cheaper than desalination, more productive and cost-effective than above-ground reservoirs, more reliable than imports, and better for Northern California than the alternatives — which include thirsty L.A. residents pulling up stakes and settling down where the water is now (move over, Sacramentans!).

L.A. is ready to do this, if it gets the money. In this year of budget surplus and deepening water crisis, the state has the money. It should invest it here, where it will do the most good for the most people, up and down the state.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.