Curtis Flowers murder conviction is overturned. Supreme Court cites bias against black defendant in Mississippi

The Supreme Court on Friday overturned the murder conviction of an African American man from Mississippi who had been tried six times by nearly all-white juries.

The justices, by a 7-2 vote, said the prosecutor had wrongly and repeatedly excluded potential black jurors because of their race.

Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh said the white prosecutor had displayed a pattern of racial bias in selecting jurors to try Curtis Flowers, the black defendant, who was charged with murdering four employees of a furniture store where he had briefly worked before being fired.

“The numbers speak loudly. In the six trials combined, the state employed its peremptory challenges to strike 41 of 42 black prospective jurors that it could have struck, including five of the six black prospective jurors in the sixth trial. We cannot ignore that history,” he said in Flowers vs. Mississippi.

He said the prosecutor had asked, on average, more than a dozen skeptical questions of each prospective black juror, while he quickly accepted whites after one question. In a 31-page opinion, Kavanaugh said Friday’s decision “breaks no new legal ground. We simply enforce and reinforce Batson by applying it to the extraordinary facts of this case.”

He was referring to the 1986 case of Batson vs. Kentucky, in which the court said that a trial judge should intervene if a prosecutor shows a pattern of excluding jurors based on their race. As a Yale law student, Kavanaugh had written about the importance of removing racial bias in selecting juries.

Justice Clarence Thomas wrote a 42-page dissent arguing the Mississippi prosecutor had “race neutral explanations” for seeking to exclude each of the black jurors. He said they knew Flowers or his family. “Any competent prosecutor would have exercised the same strikes as the prosecutor did in this trial. And although the court’s opinion might boost its self-esteem, it also needlessly prolongs the suffering of four victims’ families,” he wrote. Justice Neil M. Gorsuch agreed.

Sherrilyn Ifill, president of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, said the ruling highlights the “long and disturbing history of denying black people the right to serve on and be judged by a fair jury.”

The ruling does not mean Flowers will go free after 22 years in prison. And the court’s decision does not say or suggest that Flowers is not guilty of the shooting.

But the ruling is a rebuke to Doug Evans, the district attorney who insisted on personally prosecuting the case against Flowers in 2010 despite five earlier reversals.

State prosecutors must decide whether to retry Flowers for a seventh time.

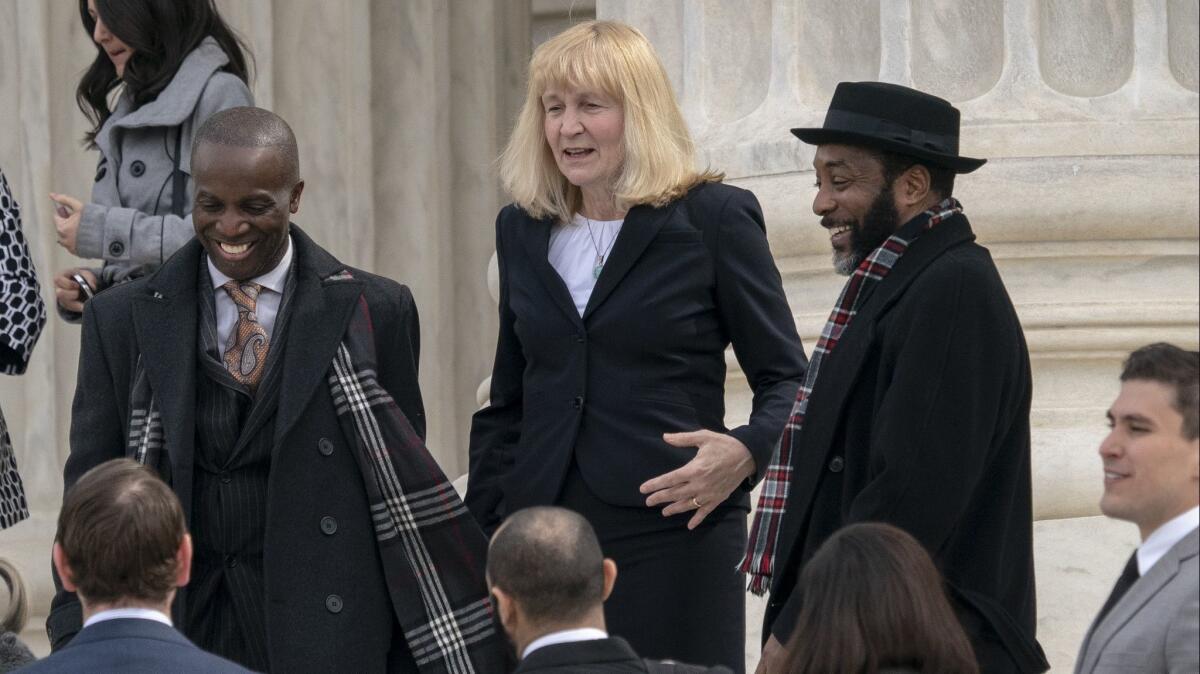

Sheri Lynn Johnson, the Cornell law professor who represented Flowers, urged the state to drop the case. “That Mr. Flowers has already endured six trials and more than two decades on death row is a travesty. A seventh trial would be unprecedented and completely unwarranted given … the flimsiness of the evidence against him.”

The Supreme Court has struggled with how to remove racial bias in the selection of jurors, because both the prosecutor and the defense attorney are usually given the freedom to exclude an equal number of potential jurors based on the hunch they will be unfavorable to their side. These are known as peremptory challenges.

The case began on July 16, 1996, when four people were found shot and dying in Tardy’s Furniture store in the small town of Winona, Miss. The victims included co-owner Bertha Tardy. When police contacted her husband, who was at home in a wheelchair, he said his wife had voiced fears of Flowers. Flowers had worked at the store for four days in early July, but was accused of dropping and damaging goods. In a phone conversation, Bertha Tardy told Flowers he was no longer employed and that she was withholding $82 from his paycheck to cover the damage.

On the same morning of the murders, police were called to a nearby garment factory where Doyle Simpson reported that someone had broken into a parked car and stolen a .38 caliber pistol. The murder weapon was never found, but it too was a .38-caliber pistol. An employee reported seeing someone, later identified as Flowers, standing near the parked car earlier that morning. Simpson later testified that Flowers was his nephew and knew that he carried a gun. About $300 was missing from the store, and a police investigator found $235 hidden in a room where Flowers slept.

Flowers left the town in September and moved to Texas. But he was returned and tried the next year in Tupelo for the murder of Bertha Tardy. He was convicted and sentenced to death, but the state Supreme Court set aside the conviction because the prosecutor had introduced evidence of the other murders. Flowers was retried in Gulfport with the same result. He was convicted and sentenced to death, but the state high court ruled again that the prosecutor had erred by introducing other evidence.

The third trial took place in Winona, and Flowers was convicted of the four murders and sentenced to death in 2004. The state high court set aside that conviction on the grounds that the prosecutor had wrongly excluded black jurors. A fourth and fifth trial ended in mistrials because the jurors could not agree on a unanimous verdict. The Constitution forbids trying a defendant again after he has been acquitted of a crime, but the ban on “double jeopardy” did not spare Flowers because he was not acquitted.

In 2010, the prosecutor tried him again. Flowers was convicted of all four murders and sentenced to death by a jury with 11 whites and one black person. This time, the state’s high court upheld the conviction, including the selection of the jury.

But the Supreme Court agreed in November to review the case of Flowers vs. Mississippi.

More stories from David G. Savage »

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.