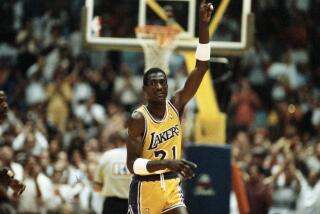

Twenty years later, Magic Johnson is ‘living proof’ of surviving HIV

Bob Costas, the television sports analyst widely considered one of the best in the country, was no different from many athletes, sports fans and basketball experts 20 years ago Monday when Magic Johnson held a news conference to tell the world he was HIV-positive.

“I was stunned,” Costas said, “and my immediate thought was, knowing what we thought we knew about HIV, we would watch Magic Johnson die a public death, that he would waste away. This was what we thought we understood about the virus, that his days were numbered.”

Now the number of days Johnson has ahead of him seems limitless when the strong, healthy-looking basketball great, onetime coach, voluble television commentator and successful businessman puts on his smile and optimism and shakes your hand.

ALL THINGS LAKERS: Magic Johnson

Chris Mullin, who played with Johnson on the 1992 U.S. Olympic basketball team, said that when he sees Johnson anywhere, his own big hand disappears into Johnson’s bigger hands. “It makes you remember,” Mullin said, “just how strong he is.”

How strong he is. Not was.

Twenty years later, some of the men who played with or against Johnson or who stood by his side when he made the HIV announcement say what Costas said.

That they thought Magic would die, sooner rather than later, and that they dreaded what they might watch. “That he would just waste away,” Mullin said. “That’s what we thought we knew.”

Kenny Smith, now a TNT studio analyst, said the moment he heard Johnson’s announcement on Nov. 7, 1991, he said one word.

“Jesus,” Smith said. “I wasn’t educated at all on what was going on with the virus. It turns out, unfortunately for him, fortunately for us, he was the best man for the job. His job was educating people on what HIV was. He helped me learn a totally new perspective. God doesn’t give us anything we can’t handle, that seemed to be Magic’s attitude.

“I don’t know if there was another person alive, not just athlete, but person, who had such goodwill earned up, who could have told us what he told us and have people feel sympathy instead of something else.”

Smith was the Houston Rockets’ team representative in 1991, and after Johnson’s announcement, the NBA asked all the team reps to attend an informational seminar about the virus and to return to their teams and, as Smith said, “educate.”

“Even some of the trainers, still working with the team at the time, weren’t educated,” Smith said. “Even people we trusted with our bodies at the time didn’t really know much. The day Magic spoke was the day some truth was brought into the situation to people who are sometimes resistant to education.”

It wasn’t only basketball players who heard Johnson on that day and expected only sadness and illness to follow.

Michael Weinstein, president and co-founder of AIDS Healthcare Foundation (AHF), said the general feeling in the HIV and AIDS community was simple. “He won’t be with us much longer,” Weinstein said.

Now, Weinstein said, Johnson is a symbol that people can live well with the disease. AHF billboards often feature Johnson’s broad, smiling face and Johnson’s name and image are on mobile testing sites and clinics around the country because Johnson is willing to be a partner to the foundation.

Michael Gottlieb, an HIV/AIDS physician from Los Angeles who, in 1981 co-wrote a study identifying AIDS as a new disease, said he remembers vividly watching Johnson play basketball after making his diagnosis public and saw another player kiss him on the head after a winning game.

“I contrasted that with the attitudes of some players and their willingness to play basketball with him or against him because of exposure to HIV through injuries,” he said. “It was a poignant moment.”

Gottlieb said that Johnson stands as “living proof” of medical progress in the treatment of HIV and AIDS.

“For many,” Gottlieb said, “HIV is a manageable condition. I heard some say that because he’s wealthy he must be getting special treatments, but it’s important to communicate that many people are getting the same results through standard therapy.”

A major component of the Magic Johnson Foundation is devoted to HIV and AIDS awareness. The foundation’s HIV/AIDS program, in partnership with the Los Angeles-based AIDS Healthcare Foundation, has established full-service treatment centers in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Oakland and Jacksonville, Fla., offering free or low-cost healthcare for those dealing with the virus. The foundation also holds events each year offering free HIV/AIDS testing. According to the foundation’s website, it has tested nearly 30,000 people and given 1,000 positive diagnoses for the virus.

At the time of Johnson’s announcement, many people did not understand the difference between being HIV-positive and actually having AIDS. Two decades ago, the typical length of time from infection to death was eight to 10 years. It was not until the mid-’90s that drug cocktails that suppress the AIDS virus came into wide use.

And not all players were unconcerned about playing basketball with Johnson. Fellow 1992 Olympic Dream Team member Karl Malone was most outspoken about his fears.

“Look at this, scabs and cuts all over me,” Malone told a reporter in New York in 1992. “I get these every night, every game. They can’t tell you that you’re not at risk, and you can’t tell me there’s one guy in the NBA who hasn’t thought about it.”

Charles Barkley, also a teammate of Johnson’s on the 1992 Olympic team, said he cried when Johnson made his announcement. He said he was also aware of NBA players besides Malone who were hesitant to, as Barkley said, “be in the same building with Magic.”

“I was cool with it,” Barkley said. “I had known people with AIDS before. The thing about Magic was that he handled it all very well, the criticism, whatnot. I think that’s just his personality, being able to handle stuff.”

Kathleen Hessert, founder and manager of Sports Media Challenge, a company that offers media and communication training for athletes and coaches, said that if Johnson had made his announcement today, in a world where social media offers instant communication via Twitter and blogs and Facebook, Johnson might have suffered much more public criticism and scrutiny.

“The degree of civility that Magic experienced at that time,” Hessert said, “you won’t find that now.” She compared what Johnson might have had to endure to what has happened to Tiger Woods in the last two years since the revelations of Woods’ marital infidelity became public.

“Twitter, blogs, those things would have been turned upside down by Magic,” she said. “I call it ‘the swarm.’ There would have been panic because, at the time, we all didn’t understand HIV and AIDS.”

Now, 20 years later, what Barkley and Smith and Mullin all remember is that Johnson was voted a starter for the 1992 All-Star game and that he represented the U.S. at the 1992 Olympics. Johnson hit a three-point shot as the final basket of that All-Star game. “I can still see that ball going in,” Smith said. “And everybody ran out to hug him and kiss him.”

NBA Commissioner David Stern, who stood by Johnson’s side on the day the announcement was made, said, “Magic changed the debate about HIV on a global scale because the person suddenly afflicted was a beloved athlete of world renown. We all assumed he would be dead soon and he was busy reassuring all of us.”

Times staff writer Dalina Castellanos contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.