A view of Weston country in Carmel

Carmel

There’s looking at a seascape. And there’s really looking at a seascape, so engrossed in the beach and the rocks and the light and the textures that you find yourself in the back of a sea cave gazing through a camera lens, nobody else on the beach for a mile or more, a rogue wave exploding at the cave entrance.

Your footprints vanish under the foam and then your feet, but all you’re thinking is Have I seen this view before? How to frame it? Then the sloshing water tickles your ankles and your knees, and you notice that much of the entrance is under a rising froth. You lurch out at last and fetch up on dry sand.

You are not very bright, it seems, but you are very happy.

This was me a couple of weeks ago on Garrapata Beach, seven miles south of Carmel. I blame euphoria photographia and several guys named Weston. And I thank them.

Amid all the painters and poets and golfers and movie gunslingers who have dominated Carmel’s public life in the last century, this rugged coastline is also a key territory in the history of American photography.

Photography pioneer Edward Weston, who haunted Point Lobos for much of the 1930s and ‘40s, won worldwide respect for the cause of fine-art photography with his meticulous, unsentimental, often nearly abstract images of nature. Then came sons Brett, a prodigy who shot black and white, and Cole, a late bloomer who shot mostly color, and a host of others with other last names.

Taken together, the Westons’ work has made this area of Monterey County not only a destination but also a sort of geo-character in American visual culture, like Georgia O’Keeffe’s New Mexico, David Hockney’s Los Angeles or Ansel Adams’ Yosemite. (By the way, it was here, not Yosemite, that Adams spent the last 22 years of his life.)

Thinking about Greater Carmel this way can make all the difference for a visitor weary of cute cottages and high-end retail. While your loved ones browse boutiques or plot tee times, you dip into one of the town’s four photography galleries.

You head out to Point Lobos State Reserve when it opens at 9 a.m. — partly because the rangers go to a “one-in, one-out” policy once the 250 or so parking spaces fill up, partly because the light is better.

“I can’t even describe the color the water was this morning,” said reserve docent Patty Oglietti. “There is no name for that shade of blue.”

Instead of settling for a stroll on predictable Carmel Beach at the foot of Ocean Avenue, you turn left on Scenic Road and follow it out to the fluttering shorebirds and shifting sands of Carmel River State Beach.

You give yourself time to head south to Garrapata State Park, where rocks and water do astounding things on two miles of often-empty beach, or you head to Big Sur beyond that.

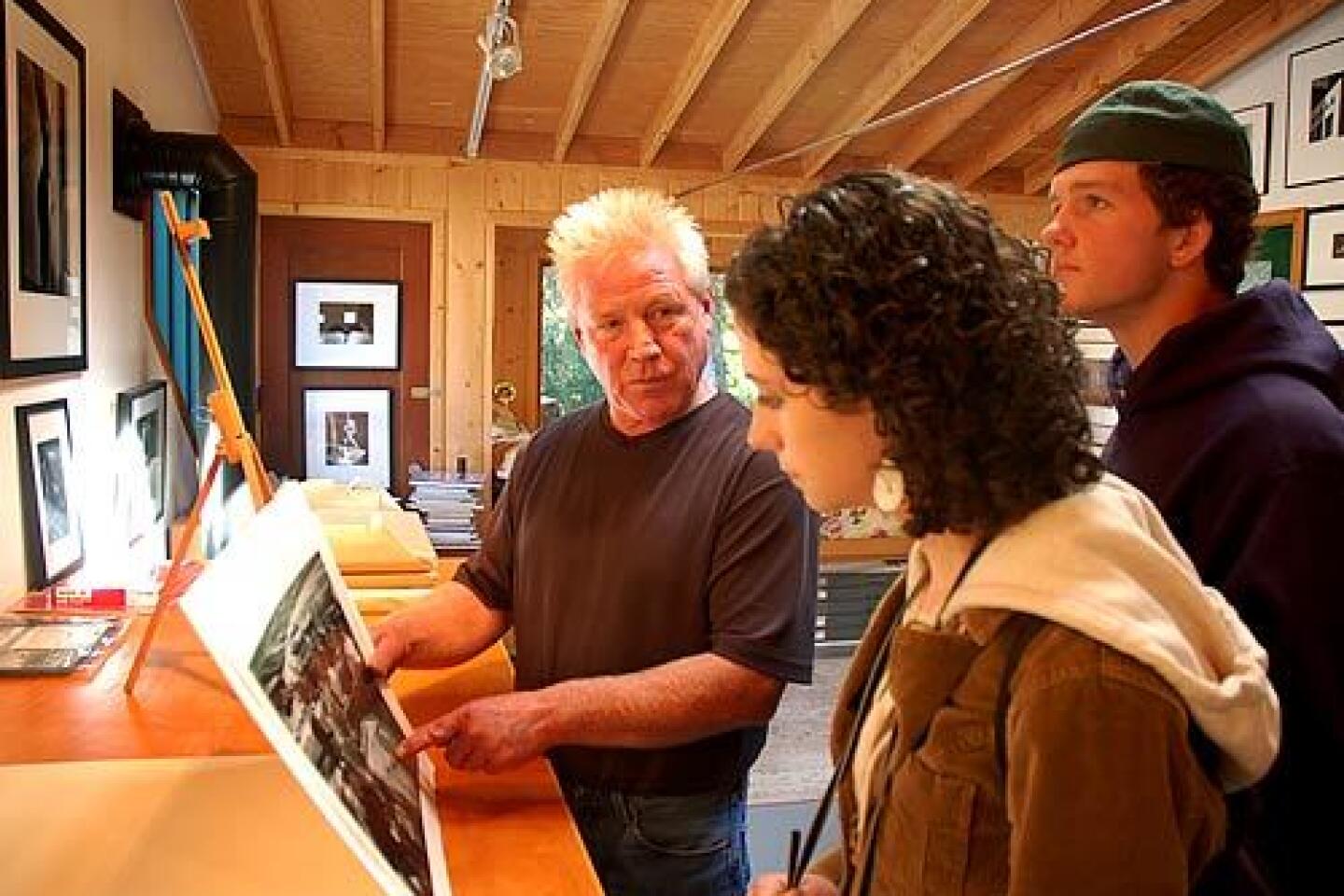

You can even bunk down in a guest cabin on Wildcat Hill, where Weston and his family built their home. I did that and wound up walking the trails of Point Lobos with my landlord: Kim Weston, 53-year-old grandson of Edward, son of Cole and, yes, a photographer. He leads workshops and shoots mostly nudes, rarely landscapes. His reasoning is understandable.

“See that dead cypress tree branch there?” he said as we reached an overlook near Pinnacle Cove. “Edward shot that in 1929. Everywhere I look, there’s one of Edward’s photos. Or one of Brett’s. Or one of my dad’s.”

Early burst of creativity

By the time Edward Weston moved to Carmel in 1929, it was already known as an artists’ colony and a playground for the wealthy. He was 42, the son of a Midwestern doctor, a photographer with little money but a growing reputation, a father of four who had been through several lovers since separating from their mother. He planned to make some money shooting portraits of Carmel’s high society.That didn’t happen, probably because the trees and rocks intrigued him more than the people.

He made some of his most admired pictures during his first six years here, including his most famous image, a 1930 still life of a pepper that half-resembled a well-muscled torso. (As his grandson tells the story, the photographer placed the pepper in a funnel and used an eight-hour exposure to get the desired depth of field.) His fingernails were always black from using amidol, a developer, in the darkroom.

Weston left Carmel in 1935 but returned three years later, settling on property provided by the father of Charis Wilson, his 24-year-old wife-to-be.

The land, about four miles south of downtown Carmel, lies a mile or so from Point Lobos. Weston, who didn’t drive, would spend hour upon hour at the water’s edge, composing frames of granite and sandstone, wind and surf, cypress and succulent, seaweed and sand, all the while wrestling with a heavy tripod and a wooden view camera, and loading 8-by-10 negatives one at a time.

Sometimes, he would shoot no more than a dozen negatives in eight hours of work. Then he would go home to his cabin, where he would process the film and make impeccable contact prints in the hours before dawn, when there was less light to leak into his tiny, imperfect darkroom.

“Art is based on order. The world is full of sloppy Bohemians and their work betrays them,” he wrote in one of his journals. A few months later, he added, “I get a greater joy from finding things in nature, already composed, than I do from my finest personal arrangements.”

While his sons forged their own careers and Charis Wilson moved on, Edward Weston dug in, surrounded by adopted cats, sometimes up to 40 of them. He shot at Point Lobos until 1948, when advancing Parkinson’s disease cut short his career. He lived in the cabin until his death in 1958.

Photographer Minor White thought Weston’s last Point Lobos photos “may parallel in content the last quartets of Beethoven.”

Home on Wildcat Hill

When Kim Weston and his wife, Gina, welcomed me to Wildcat Hill 49 years later, the tiny darkroom was still largely as Edward had left it, the walls painted black, the hand-labeled chemical jugs, the developing trays lined up on a shelf, family photos leaning here and there. (There has been quite a lot more family to photograph in more recent years: Apart from Edward’s two wives and four children, Brett had four wives and one child, and Cole had four wives and seven children. Kim and Gina have a teenage son, Zach.)There were more photos in the Bodie House, which was built as a garage in 1938 and converted into a writing studio for Wilson. The cabin, updated, outfitted with bathroom, kitchenette and windows facing the forest, is set behind and above the Weston home and Kim Weston’s studio.

The Westons rent it out for $150 nightly, most often to photographers who are taking one of their workshops. Nearby stands a sturdy picnic table and a patio full of abalone shells and old animal bones. To reach all this, you make an abrupt turn off the coast highway and creep up a curving, cliff-adjacent, unpaved driveway that concentrates a driver’s mind wonderfully.

I liked the room but didn’t spend a lot of time there. Wielding my little digital camera, I would go out and get sandy at Carmel River State Beach or soaked at Garrapata, looking for glimpses of old photos, prospecting for new ones. Then I would clean up and head into town.

The first stop was the Weston Gallery, founded in 1975 by Cole Weston’s ex-wife Maggi, with encouragement from Adams. Along with several of Edward Weston’s pictures printed by Cole Weston ($4,000 to $7,000), I saw Asian landscapes by Michael Kenna; South American landscapes by Jeffrey Becom; photo fantasies by Jerry Uelsmann; portraits by Yousuf Karsh; and — aha! — an 11-by-14-inch Brett Weston print of Garrapata Beach in 1954, all rocky geometry, misty shore and distant hills, for $12,000.

Next stop was Photography West, the Weston Gallery’s rival since 1980, with its own print of Weston’s Garrapata Beach shot, for $9,500, and a separate room named for Adams. Although Adams’ mountain pictures have always commanded more attention, his archive is full of images made between Big Sur and Pebble Beach of rocky slopes, dense forest, breaking waves and foggy roads.

The gallery, still run by founder Carol Williams, also includes coastal scenes by Morley Baer, seashells and nudes by Imogen Cunningham and forest scenes in startling color by Christopher Burkett.

Three years ago, that would have been just the beginning of a Carmel photo gallery crawl. But three recent closures, including the Josephus Daniels Gallery downtown and the satellite Ansel Adams Gallery in the Highland Inn, have thinned the ranks.

As April began, the only other photography-only spaces here were the 6-year-old Robert Knight Gallery, which showed Robert Knight’s color-drenched panoramic landscapes from around the world, and the nonprofit Center for Photographic Art, a descendant of now-defunct Friends of Photography, founded in 1967 by a group that included Brett Weston and Adams.

Photographs spring to life

Moving between the coast as photographed and the coast itself is like working two jigsaw puzzles at once. Even if you haven’t encountered Edward Weston’s exacting black-and-white images, you’ve probably seen some of Brett Weston’s seascapes from Monterey Bay or a nude from his glass-walled Carmel Valley swimming pool, or dunes from Oceano. Or you’ve seen Cole Weston’s shot of the wave-lashed Big Sur headlands or maybe his oddly becalming shot of the rolling hills of Palo Corona Ranch on a half-cloudy day.A poster of that last image hung on my living-room wall for much of the 1990s. Driving north about two miles from the Weston property on my first morning in Carmel, I glanced to my right, then glanced again. There they were, the hills from the picture.

The light and sky weren’t quite the same, of course — in 45 years of driving past the spot where that shot was taken, Kim Weston told me, he has never seen them quite the same. But most everything else matched, from the curving path to the black cows. After two days of driving past the spot on the way elsewhere, I gave up fighting the urge, found a place to park, hopped out and snapped my own lesser homage to that moment Cole Weston caught in 1962.

You would think this kind of learning-by-copying would be even easier on the 554 above-water acres of Point Lobos, where so many Weston images were made. But the game is different now. Most visitors, uninterested in producing a handcrafted darkroom masterpiece the old-fashioned way, arrive bearing lightweight digital cameras that can go practically anywhere. But the public is now forbidden from roaming off-trail as the Weston boys did.

Of course, you can always take Kim Weston’s approach: Bring binoculars and leave the camera at home.

As we prowled the trails of the point, Weston raised those binoculars to check the surf or peek into beloved nooks and crannies, remembering the shoots gone by, inlets he has explored by kayak, groves he has seen in thickest morning fog. He also had a handy answer for why, though the place is teeming with deer and otters, none made it into any Weston pictures.

“They move,” he explained.

Eventually, we made our way south to a sandy area now known as Weston Beach. Edward’s ashes were scattered here, as were Brett Weston’s in 1993 and Cole Weston’s in 2003.

“It’s sort of the family cemetery,” said Kim, pointing out a familiar rock formation, then another, then nudging a loose piece of stone with his toe.

“That piece used to be up here,” he said. “It broke off. Like any beach, it’s always changing.”

As the conversation meandered, I hovered with camera in hand, trying to catch a shot of foam flying over a well-positioned rock. Weston watched and waited with a knowing grin. Eventually, I got something, and we retreated to Wildcat Hill.

That’s when my host pulled out a volume of “Edward Weston: His Life and Photographs,” and there on Page 130 was the rock where we had been waiting. Except that the black-and-white rock on the page had been shot from a better angle, the foam flying higher and wider, a wholly different order imposed by nature and the artist, working together, 62 years ago.

Discouraging? Nah. I got to hear stories, taste that salt air and sink my boots into the sand. And my fingernails are still clean.

chris.reynolds@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.