The U.S. airstrike that killed a top Iranian general also eliminated another key player

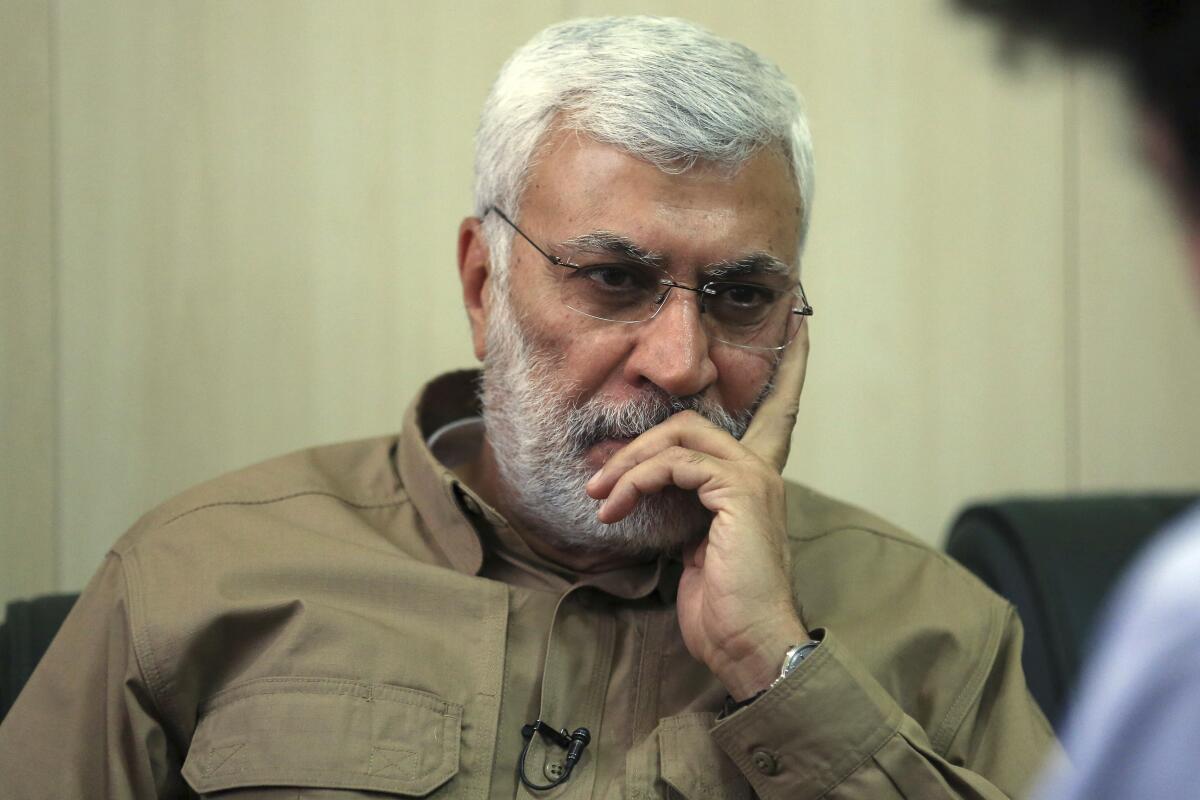

Iraqi paramilitary leader Abu Mahdi Muhandis, a bespectacled man with the mien of a professor, arrived at Baghdad International Airport to greet his personal friend and longtime ally Iranian Gen. Qassem Suleimani, commander of the elite Quds Force.

Moments later, after the two men and their companions had climbed into an SUV and headed onto the highway out of the airport, a U.S. drone fired a pair of missiles, turning the vehicle into a fiery hulk. Both men died in the strike early Friday.

While Suleimani’s death by order of President Trump ratcheted up tensions across the Middle East and stoked fears of an all-out war between the U.S. and Iran, killing Muhandis means the U.S. could face the wrath of tens of thousands of militia members.

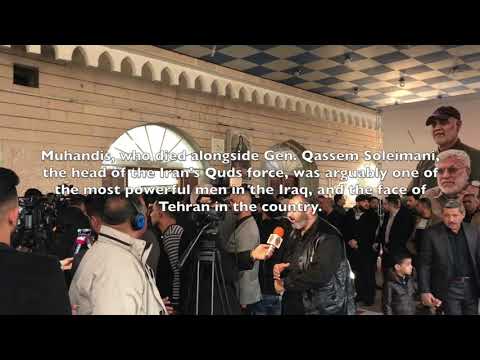

Muhandis, a onetime political dissident, suspected terrorist attack mastermind, lawmaker and militia leader, was arguably one of Iraq’s most powerful men. For many, he was the face of Iran in the country.

The vestiges of his power were on display Monday in Baghdad’s Karada district, where thousands of officials, political and religious leaders, fighters and militiamen gathered in the halls of the local mosque to pay their respects to Muhandis, who was 65, with all the pageantry of a state occasion.

In his role as the deputy commander of the Popular Mobilization Forces, a grouping of Shiite-dominated paramilitary factions created in 2014 to battle Islamic State militants, he was the driving figure behind transforming disorganized bands of religiously driven volunteers into an official branch of Iraq’s armed forces. It has since morphed into a political party with significant economic interests.

Muhandis’ rise, along with his deep connections with the top echelons in both Iraq and Iran, helps illustrate the often complicated history between the two nations.

Iran launched a series of missile attacks aimed at bases in Iraq. Iranian state television said the missiles were launched as the opening of Tehran’s “revenge” for the U.S. killing of a top Iranian general.

The influence by Muhandis, who was best known by his nom de guerre but whose given name was Jamal Jaafar Ibrahimi, began when he was a member of the Islamic Dawa, the Shiite political party, whose cadres include former Prime Ministers Nouri Maliki and Haider Abadi, but which in the 1970s was the target of a vicious crackdown by Iraq’s Baathist government. When Saddam Hussein seized power in 1979, Muhandis fled to Kuwait.

The Dawa, meanwhile, had moved its headquarters to Iran in 1979. With the help of Tehran’s new leaders, Muhandis and other party members waged an insurgency campaign against countries seen as supporting Hussein.

One of those countries was Kuwait: In 1983, a Kuwaiti court later alleged, Muhandis was part of a team of operatives linked to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps that conducted a series of bombings in Kuwait City on the U.S. and French embassies, the airport and the country’s main refinery. It was an early use of transnational Shiite irregular forces now seen in all battlefields involving Tehran.

Muhandis escaped to Iran before he could be arrested. There, he spent much of the next two decades as a political operator and a leader in what was known as the Badr Brigade. The group has since become a political party, with its armed wing part of the Popular Mobilization Forces.

The 2003 U.S.-led invasion of Iraq enabled his return to his home country, where he served as a security advisor in the first post-Hussein government before gaining a seat in parliament in 2005. But when U.S. officials realized that a wanted terrorist was now a member of parliament and raised the matter with Iraqi officials, he fled again to Iran, returning only when the Americans withdrew in 2011.

In the intervening years he agitated for ever-stronger links between Iraq and Iran — a position he personified in many ways: He was a dual citizen of both countries, spoke fluent Arabic and Persian, was married to an Iranian woman and had a house in Tehran. U.S. cables published by WikiLeaks describe Muhandis as a “member of the Quds Force,” the elite branch of Iran’s Revolutionary Guard specializing in irregular warfare, and a leading figure in several major militias that, with Tehran’s backing, had fought against U.S. troops.

President Trump sends 2,500 more Marines to the Middle East, the latest fallout of his decision to kill a top Iranian official.

He was later designated as a threat to peace and stability in Iraq by the U.S. Treasury because of that association; but with the ties to Iran came Suleimani, a figure that came to be the bedrock of Muhandis’ influence, eclipsing even that of other close associates of Iran such as Iraqi militia leader Hadi Ameri.

“Muhandis was very capable in his own right but he had that ace up his sleeve, namely Suleimani,” Michael Knights, an expert at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, said in a phone interview Monday. “If you got into an argument with Muhandis, even if you started to win it, he only needed to whip that phone out and you would lose.”

Despite his ties to Iran, Muhandis nevertheless found himself fighting on the same side as the Americans in 2014, when Islamic State extremists swatted aside entire Iraqi army brigades and took over a third of Iraq.

With the army essentially collapsed, more than 100,000 mostly Shiite volunteers along with militias already formed since 2003 rose to stop the extremists’ blitzkrieg. Muhandis unified the militias, organizing them into the Popular Mobilization Forces, or Hashd al-Shaabi, as they’re known in Arabic — all with Iran’s help.

“Muhandis was the Hashd, and the Hashd was Muhandis,” said Ahmad Assadi, a spokesman of the political bloc associated with the Popular Mobilization Forces.

Muhandis was also seen as a guarantor of some measure of discipline among the militias, which, despite ostensibly operating under the aegis of the state, have acted on their own authority in the past and would clash with regular troops.

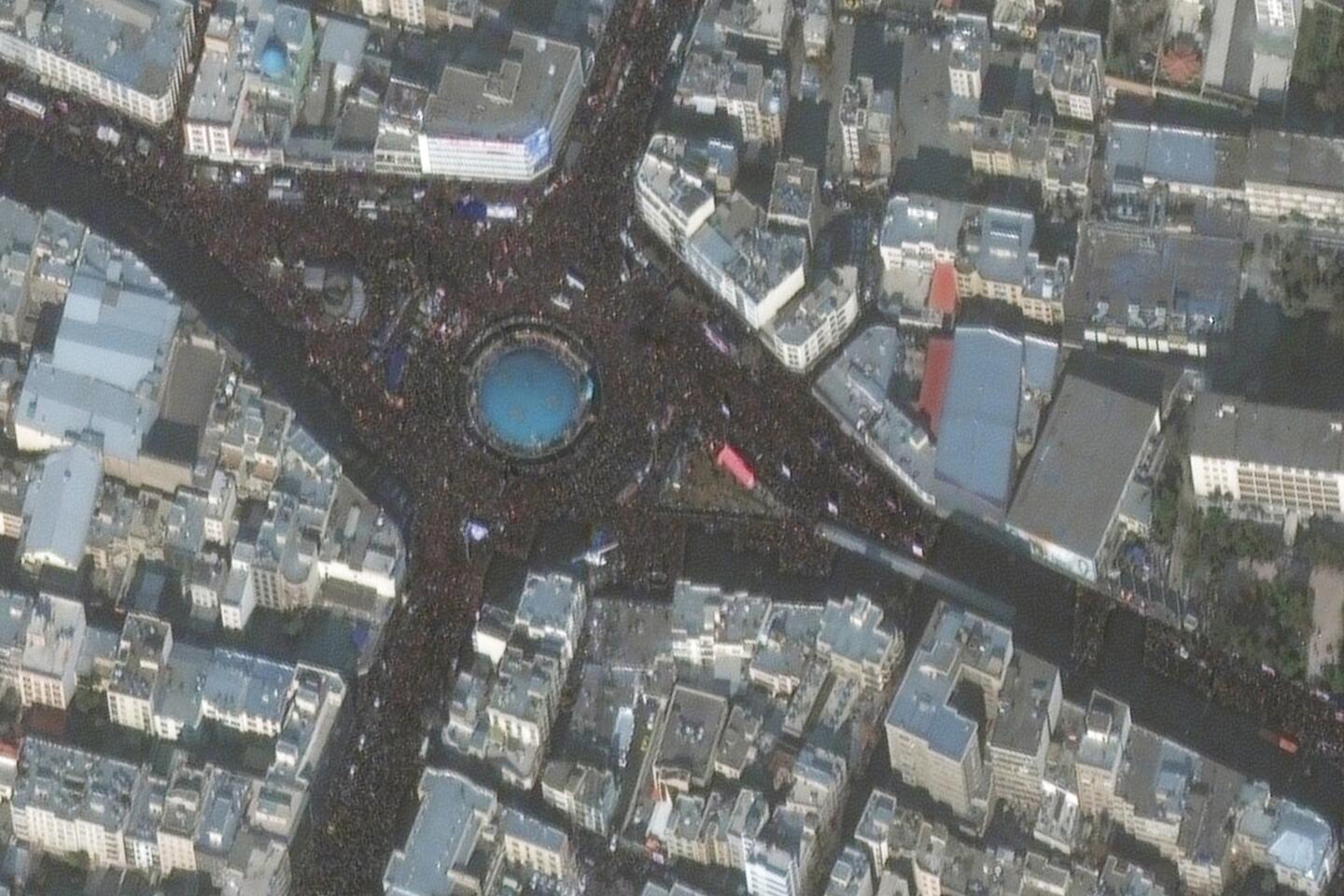

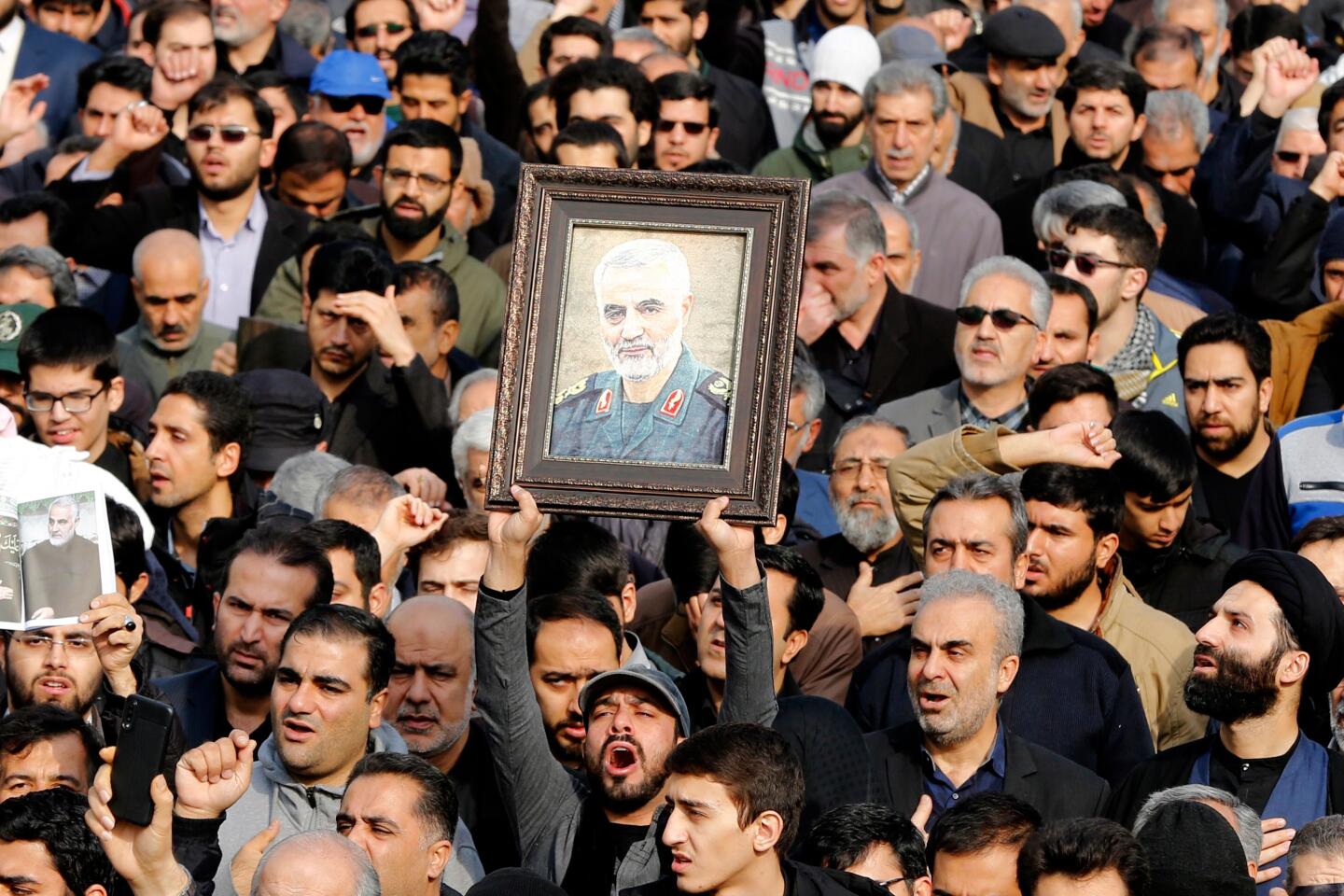

The funeral for Revolutionary Guard Gen. Qassem Suleimani drew a crowd in Tehran said by police to be in the millions.

“He was the safety valve between the state and the nonstate groups,” said Yazan Juboori, a leader in the Popular Mobilization Forces who described Muhandis as “godfather”-like figure for him. He also said Muhandis reined in attacks on “foreign interests” in Iraq. “He was the one who would calm things down, controlled the situation and told people this would hurt the interests of the country.”

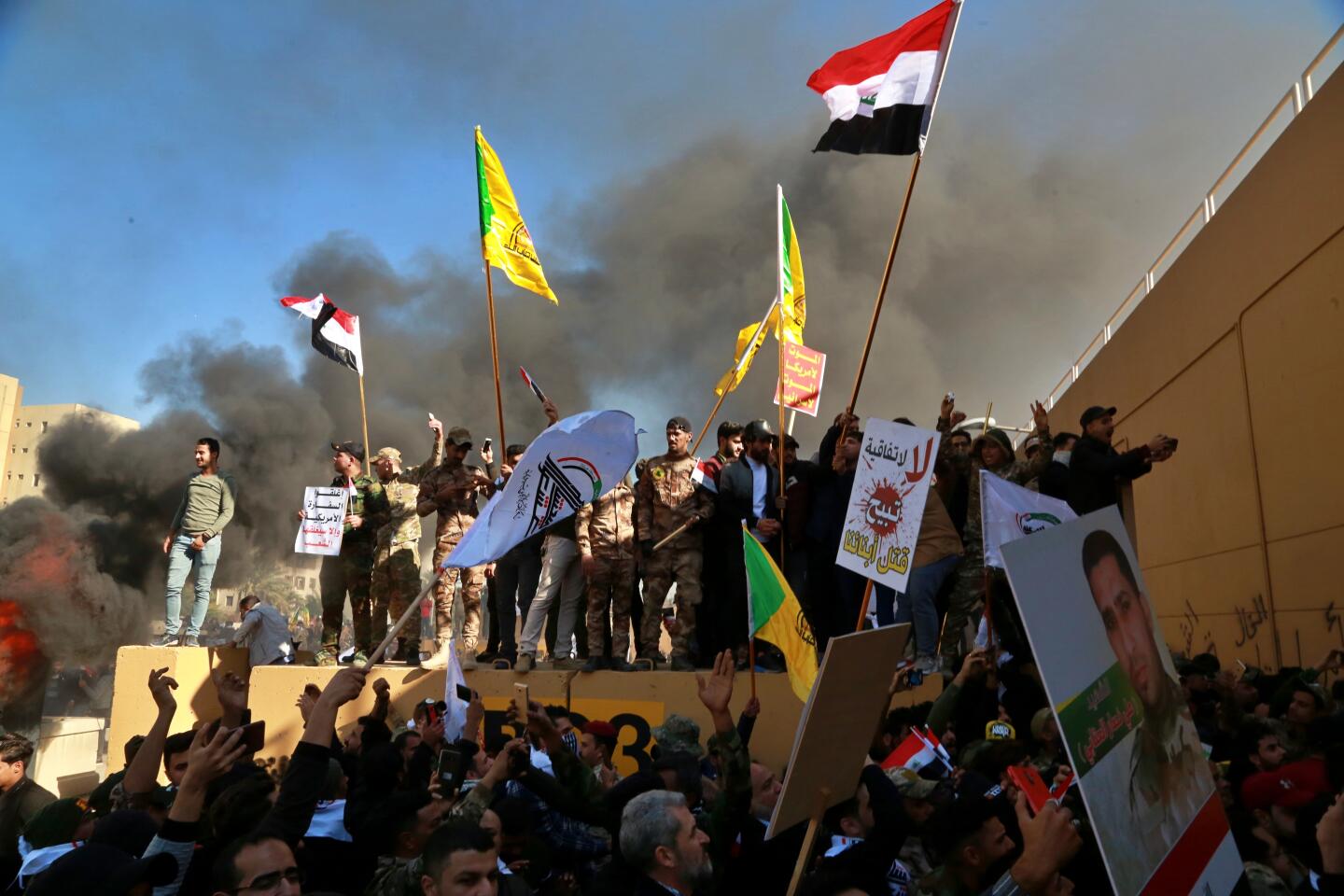

It was a part Muhandis played again when pro-Hashd demonstrators stormed the U.S. Embassy compound last week in retaliation for a U.S. strike on Kataib Hezbollah, a militia he helped found.

According to Adel Abdul Mahdi, Iraq’s caretaker prime minister, in a parliamentary speech Sunday, Muhandis played “a pivotal role in convincing protesters to withdraw from the perimeter of the U.S. Embassy.”

With Muhandis’ death, said Abu Ali Akbar, a mourner in the Karada mosque Monday, the U.S. was no longer welcome.

“We have no issue with the American people, but the soldiers here should go back home,” he said. “Here there are no interests for you any more, only enmity.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.